The post-pandemic recovery in manufacturing employment has been remarkable. As we pointed out in a recent EIG report, this is the first time manufacturing jobs have fully recovered from a recession in five decades.

Glitzy investment announcements from businesses that make everything from electric vehicles to semiconductors — paired with enormous growth in manufacturing construction — might also give the impression that a flourishing new era of manufacturing employment, in which the sector recovers some of its faded prominence as a large source of good-paying jobs, has just begun.

It’s not likely.

While this recovery has been impressive in historical terms, there is no sign yet that we are witnessing a fundamental break from the sector’s long-run decline as a source of employment for American workers. Even amidst a historic employment recovery, manufacturing accounts for a smaller share of jobs than it did in 2019.

And there are signs that those hoping for an “everything bagel” outcome that reshores critical sectors and does so in struggling regions while offering high-wage, unionized jobs might be in for a disappointment. Tradeoffs may still exist after all.

We highlight three such indicators.

The manufacturing jobs boom is not reaching the places most exposed to the “China Shock.”

There is a bipartisan desire to address the challenges of economically struggling places by boosting manufacturing employment. Is it happening? Is the historic recovery in manufacturing employment since the pandemic actually reaching these places? Not yet.

One place to look is the communities hit hardest by the “China Shock,” which was famously quantified by economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson in a 2013 paper. These are the parts of the U.S. whose local manufacturing ecosystems took the biggest hit from cutthroat competition from Chinese imports in the 2000s, with negative effects that in many places have persisted.

While policymakers are hoping that the manufacturing boom will finally bring relief to these communities, post-pandemic manufacturing job growth is disproportionately happening in places that were least exposed to the China Shock.

Breaking down U.S. counties by the degree to which they were exposed to competition from Chinese imports during the 2000s, we used the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) to find that the most exposed places are not participating in the manufacturing employment boom. Indeed, the hardest-hit places still have fewer manufacturing jobs than they did before the pandemic.

This could change, of course, as the manufacturing construction boom starts to yield new factories. Brookings Metro has tracked private manufacturing investment announcements since 2021, finding that they have indeed been concentrated in places hit hardest by the China Shock. But at least so far, such investments have not yet altered local labor market realities.

Manufacturing job growth is overwhelmingly non-union.

The manufacturing jobs boom has not been a major boost to labor unions, according to the CPS, or Current Population Survey. By 2023, union manufacturing employment was down 6.8 percent since 2019, while non-union manufacturing employment was only down 1.3 percent.

(Source note interjection: Estimates of manufacturing employment in the CPS, unlike in the QCEW, still do not show a full manufacturing recovery as of 2023. While the QCEW is a more reliable source for overall job numbers, only the CPS tells us whether jobs are unionized or not. Throughout this analysis we use the QCEW unless otherwise specified.)

States that do not actively encourage unionization are experiencing stronger manufacturing growth as well. There are 170,000 more manufacturing jobs in states with Right-to-Work laws than there were in 2019, a growth of 2.7 percent. Jobs in states without a Right-to-Work law actually shrunk by 1.2 percent, or 78,000 jobs.

This is not just a post-pandemic trend. Since 2010, manufacturing employment has grown 18 percent in states that currently have Right-to-Work laws on the books, more than double the 8 percent growth rate in states without them.

The trend is even more stark when looking at union membership directly. Since 2010, union members in manufacturing have declined by 16 percent, while non-union manufacturing employment is up 11 percent, according to the CPS.

Notably, incentives in both the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act aimed to steer manufacturers towards cooperating with labor unions. At least so far, there is little evidence these provisions are bearing fruit at scale.

Perhaps that should not be surprising. While unions can provide benefits to their members, there is strong evidence suggesting that unionization generally reduces employment and establishment survival. Right-to-Work laws have been shown to increase long-run manufacturing employment. Any policy incentives meant to reverse these trends will be fighting an uphill battle.

Manufacturing job growth is largely following population growth.

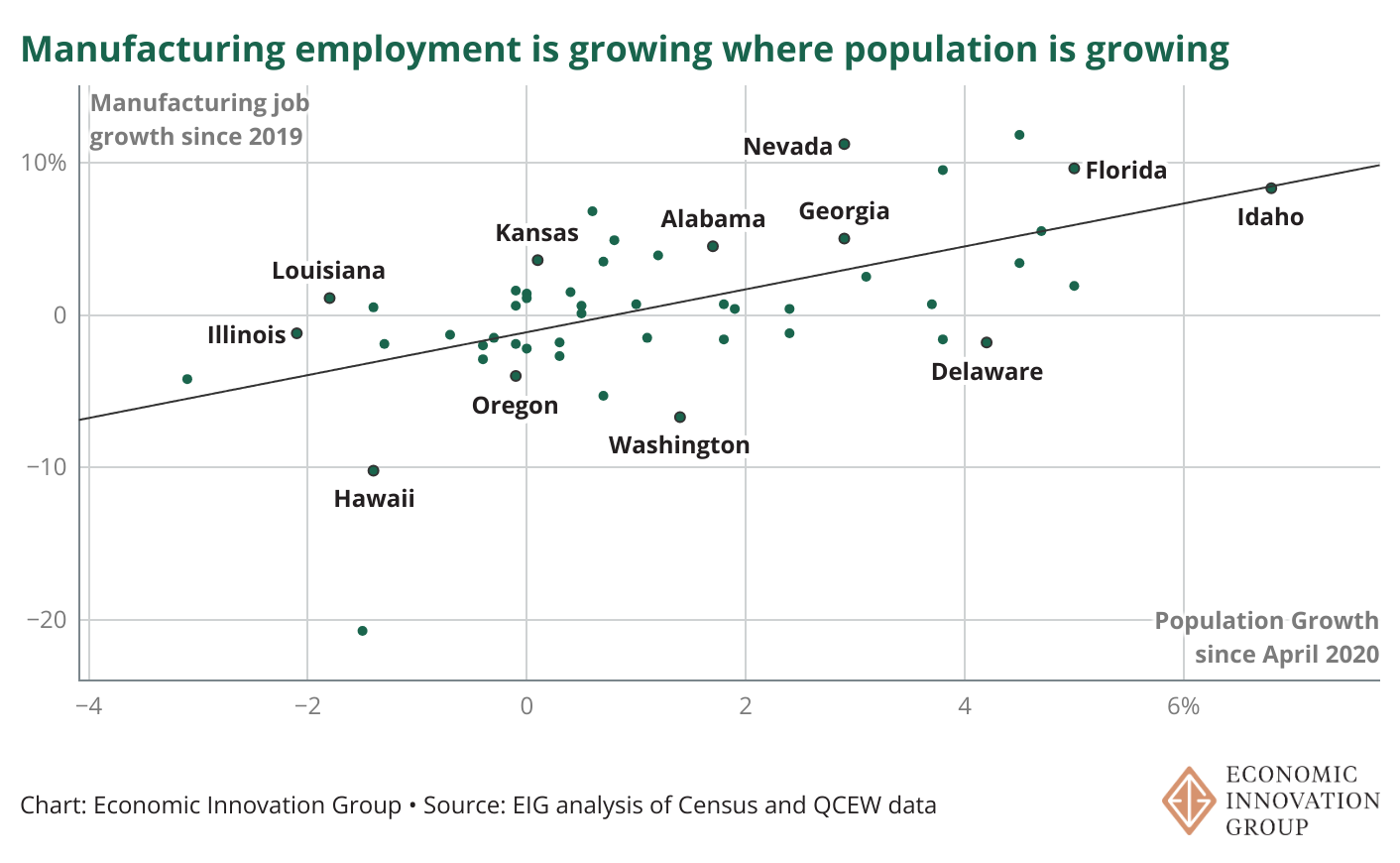

Instead of reaching places struggling with economic and demographic decline, job growth is primarily happening in states to which Americans are moving.

States across the Sun Belt are attracting migrants from across the country. They are also the main drivers of manufacturing job growth nationwide. Five states — Texas, Florida, Georgia, Arizona, and Utah — have accounted for 62 percent of post-pandemic manufacturing job growth. Pre-pandemic, the top five states by growth only accounted for about one-third of new manufacturing jobs.

It is unclear exactly what is driving manufacturing growth faster in places with rapid population growth. A growing population means a growing workforce, which is one factor that employers will often consider, so there is reason to suspect population growth is causally linked to manufacturing growth.

But there are also other factors that drive both. The criteria manufacturers use to choose investment locations share similarities with those of families deciding where to live. Manufacturers weigh differences in tax or regulatory policy, just as families consider income tax rates and housing costs. Places where it is easy to build tend to keep down the costs of living and the costs of doing business.

Whatever the direction of causality, places that are desirable to families are clearly proving desirable to manufacturers. This is one more sign that revitalizing struggling places through manufacturing job growth will be a challenge.

Cautionary Data

The faster-than-usual jobs recovery in the manufacturing sector may seem cause for a victory lap. But the data we have seen so far illustrates the deep challenges that confront any policymaker who wants to both revive manufacturing job growth and steer it toward goals like regional revitalization or restoring unionization rates.

Incentives still matter on the margin. But they can only go so far, particularly when they have multiple — and sometimes conflicting — goals. Cheerleaders of the post-pandemic manufacturing boom need to be realistic about just how far it can go.