No, we are not producing too many STEM graduates

The social media firestorm over H-1B visas over the last few weeks has resurfaced a long-running debate about the return to earning a STEM degree. Critics of skilled immigration argue that visa holders are displacing American STEM graduates from STEM careers. They point to research from the Census Bureau showing that 72 percent of STEM graduates work in non-STEM occupations. As we will show in this piece, this data point masks a much more interesting, complicated story.

Is such a high percentage of STEM graduates going into jobs not classified as STEM a good or a bad thing? There are two stories you could tell:

First is the negative story. Perhaps social pressures to study something technical have fooled too many students into majoring in STEM fields, for whom there simply aren’t enough jobs. Graduates not landing STEM jobs are left with useless degrees that don’t help their career prospects.

There is a second, much more positive possibility. Maybe STEM graduates’ skills are in high demand across the economy, and employers in other sectors are willing to pay a premium for them. Students understand that earning a STEM degree will be good for their careers even if they intend to enter a different field.

On balance, the evidence is much stronger for the second, positive story.

What are STEM jobs, anyway?

First, it’s worth noting that there are major classification problems with the Census analysis’ STEM retention rate.

Census identifies 27 percent of STEM majors as working in STEM occupations. But it tracks another 14 percent going into “STEM-related” jobs, overwhelmingly in healthcare. Most people would consider physicians and nurses as holding STEM jobs. Since we have no undergraduate medical education in the United States, every pre-med science major who successfully becomes a doctor is counted as someone purportedly leaving STEM.

There are other cases in which students graduating with STEM degrees clearly are working in fields directly aligned with their degrees, even if such occupations are not considered STEM. Take economics, a STEM major, as an example. BLS estimates there are only 17,500 workers whose profession is “economist.” Yet the 2023 American Community Survey identifies more than one million full-time, year-round workers in the United States who majored in economics. They work as managers, investment analysts, financial advisors, and other business careers. In many of these occupations, they earn more money on average than economists themselves.

Many STEM graduates are taking higher-paying jobs in other fields.

Among the 13.7 million STEM majors working in non-STEM jobs, 36 percent earn more than STEM majors do in STEM jobs. The median STEM major in a STEM job made $110,000 in 2023. Over 4.9 million STEM majors earned at least that much in non-STEM jobs that year. That total is comparable to the 5.1 million STEM majors who work in STEM jobs in total.

The share of graduates who exceed this earnings threshold is even higher in some categories of majors. Among engineering majors who go into non-STEM careers, 49 percent earn more than the median for all STEM occupations.

STEM graduates earn a huge premium in non-STEM occupations.

Still, comparing average earnings for STEM majors across occupations doesn’t quite tell us whether STEM students are systematically misjudging the value of their degrees. For example, a math major seeking to become a high school math teacher should not expect his absolute earnings to match those of his classmates who go on to careers in AI. Yet his degree may still substantially improve his expected earnings. We need to think on the margin.

In other words, does a STEM degree boost your earning power even if you do not go into a STEM occupation?

The answer is yes.

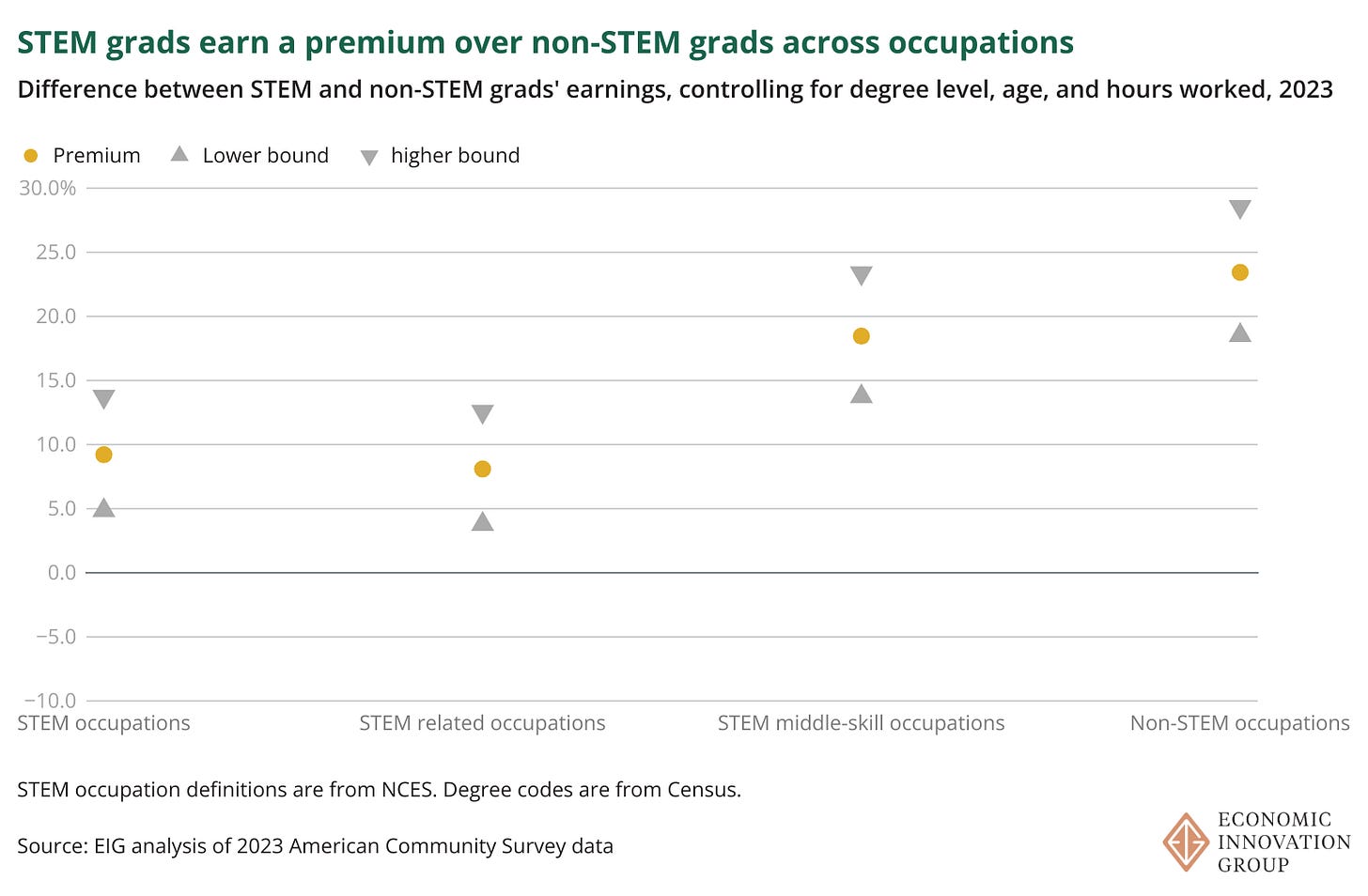

Controlling for degree levels, age, and hours worked, having a STEM degree earns you a sizable wage premium over non-STEM graduates in all occupation groups. In STEM occupations, having a STEM degree is associated with a 9 percent earnings boost. In non-STEM occupations, having a STEM degree boosts your earnings by 23 percent. STEM degrees also earn workers sizable premiums in STEM-related jobs. All of these results are statistically significant:

Every degree type sends graduates to other fields of work. That’s not always a problem.

STEM is hardly alone in sending graduates to other fields. Fewer than one-quarter of art graduates work in art occupations. Fewer than half of business majors work in either business or management occupations. Within-field retention rates alone cannot help you differentiate between fields over-producing graduates and fields producing highly-coveted graduates. Earnings data suggests that STEM programs are largely producing the latter.

Not all college students choose their major purely based on economic returns, nor are such returns the only legitimate reason to choose one degree field over another. Yet the data seems overwhelmingly consistent with the story that many more students are majoring in STEM fields than going into STEM occupations precisely because earning such degrees yields financial returns across a wide range of jobs.

That’s a success, not a failure.

–

You can see the code and data behind this analysis in this Github repository.