Raising the SALT cap will not help low-income, rural, or pro-Trump places

The fight over the future of the State and Local Tax deduction (SALT) represents an early test. Will the expansion of President Trump’s coalition of working-class voters, whose support was so critical to his victory in last November’s election, actually translate into a more populist tax agenda in 2025?

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) dramatically limited the reach of the SALT deduction, prohibiting each household from deducting more than $10,000 of state and local tax payments from their federally taxable income. Like the rest of TCJA’s changes to the individual tax code, this $10,000 cap on the SALT deduction is set to expire at the end of 2025.

Congress is therefore now considering its options, which include:

Repeal the cap altogether

Raise the cap higher than the current $10,000

Leave the cap in place at $10,000

Eliminate the SALT deduction itself (effectively a $0 cap)

Tax policy experts have already concluded that any reform to expand the SALT deduction will be both expensive and highly regressive, offering little or no benefit to most working or middle-class households. The Tax Policy Center, for instance, has found that repealing the SALT deduction cap would cost $1.2 trillion over a decade, 93 percent of which would go to households in the top income quintile. Even striking a compromise to raise the cap to $20,000 would benefit fewer than one percent of middle-class households.

But SALT reform will also benefit certain kinds of places more than others, in particular high-income, urban, and Democratic parts of the country. Raising the cap, while coming at a steep cost to taxpayers, will also do little to benefit distressed, rural, or pro-Trump communities.

The SALT deduction does virtually nothing to benefit low-income places.

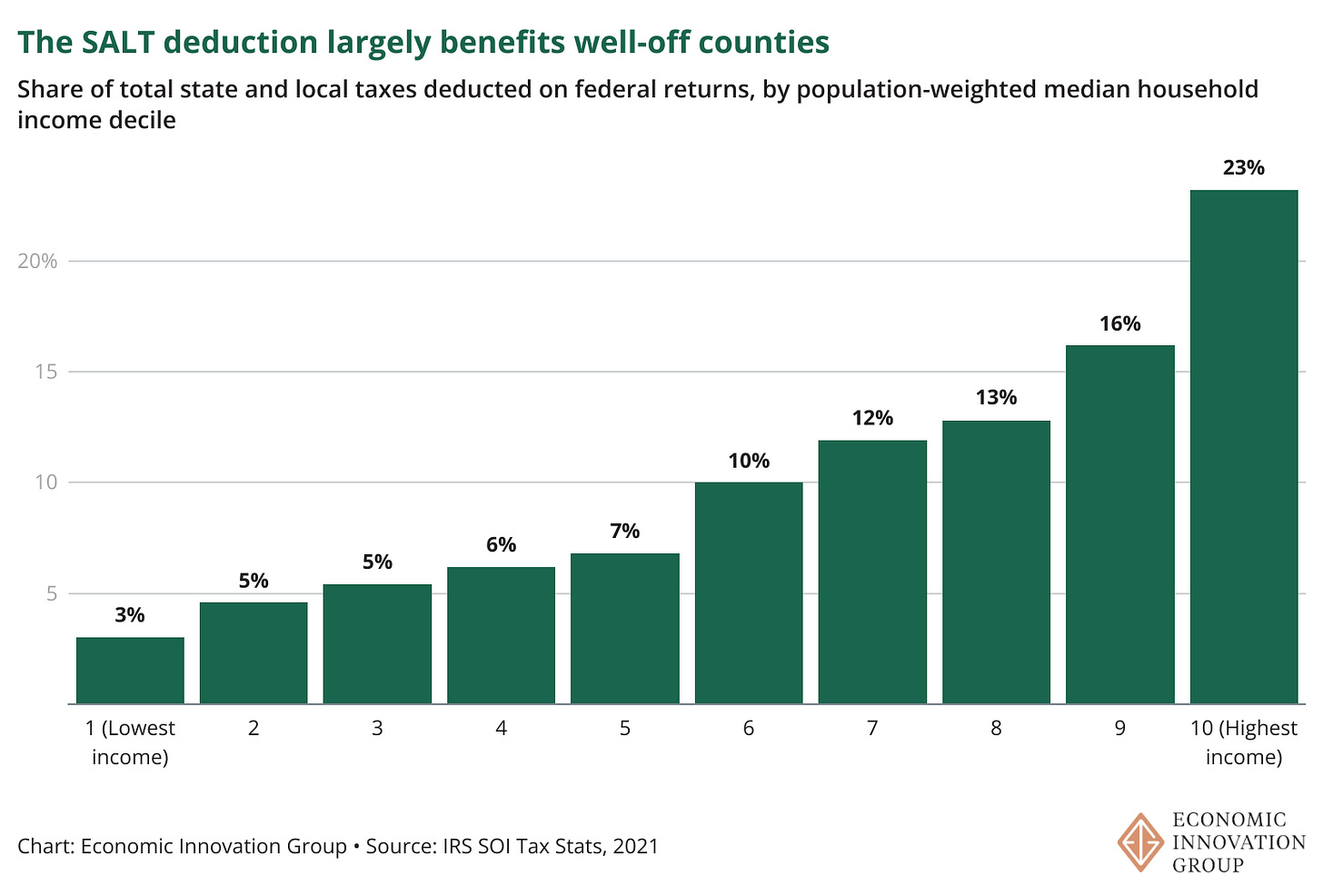

Today, even the capped SALT deduction largely benefits well-off places, particularly those concentrated in high-tax states. Using IRS statistics from individual federal tax returns in 2021, I find that the benefits of the SALT deduction largely flow to more prosperous communities.

Counties in the bottom five median household income deciles, weighted by population take home a quarter of the benefits from SALT, while more prosperous counties combine for three-quarters. (Please see the end of this post for the rationale behind population-weighting and other methodological points.)

The SALT deduction is also tilted against counties that voted for the President in November. Bucketing counties into deciles according to President Trump’s vote share, I find that the bulk of the SALT deduction’s benefits are received by households in counties where President Trump performed worst in November’s election.

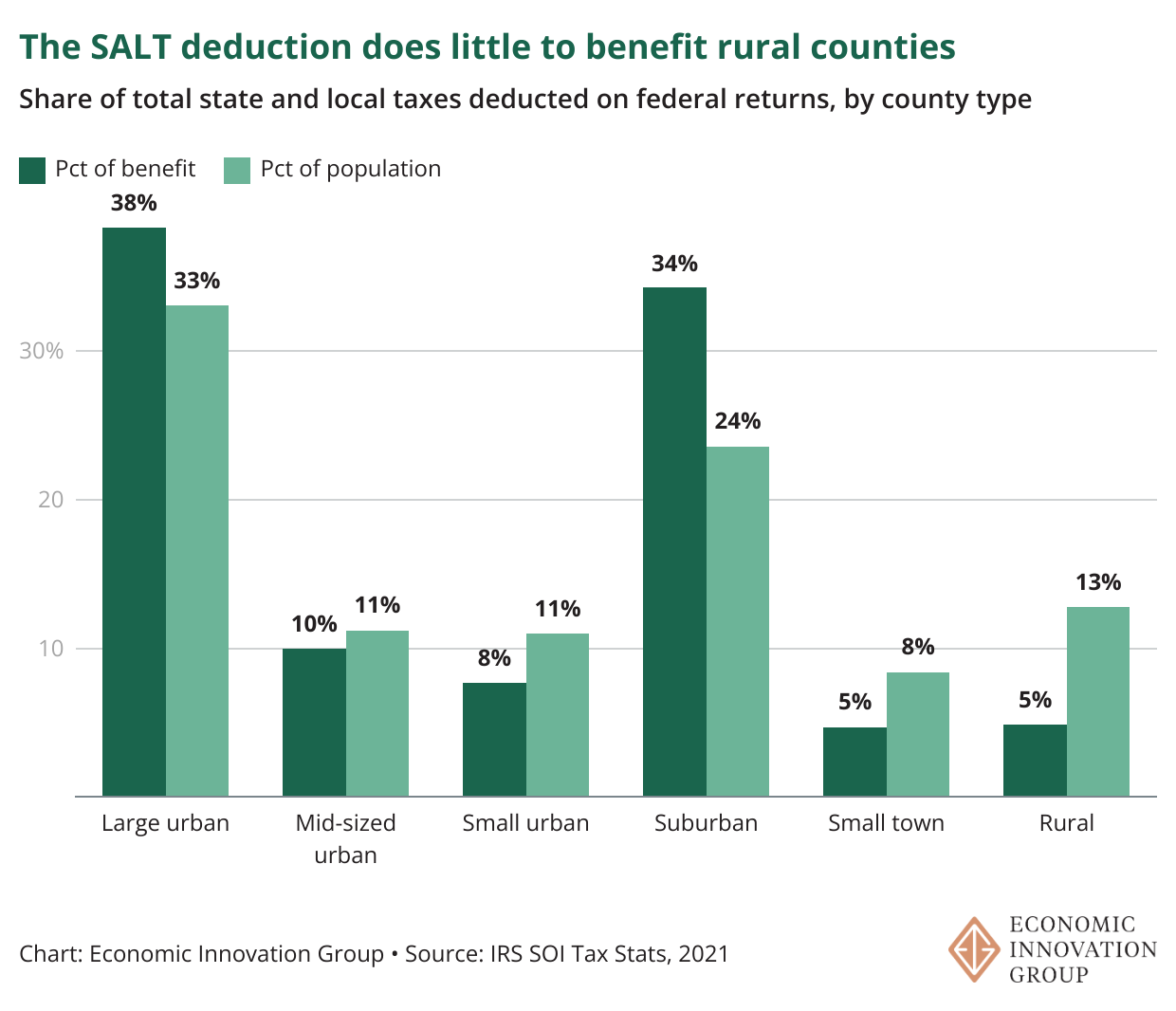

The deduction does very little to benefit rural communities. Five percent of state and local taxes deducted on federal returns come from taxpayers in rural counties, which is less than half the share of the national population that resides in rural counties (13 percent).

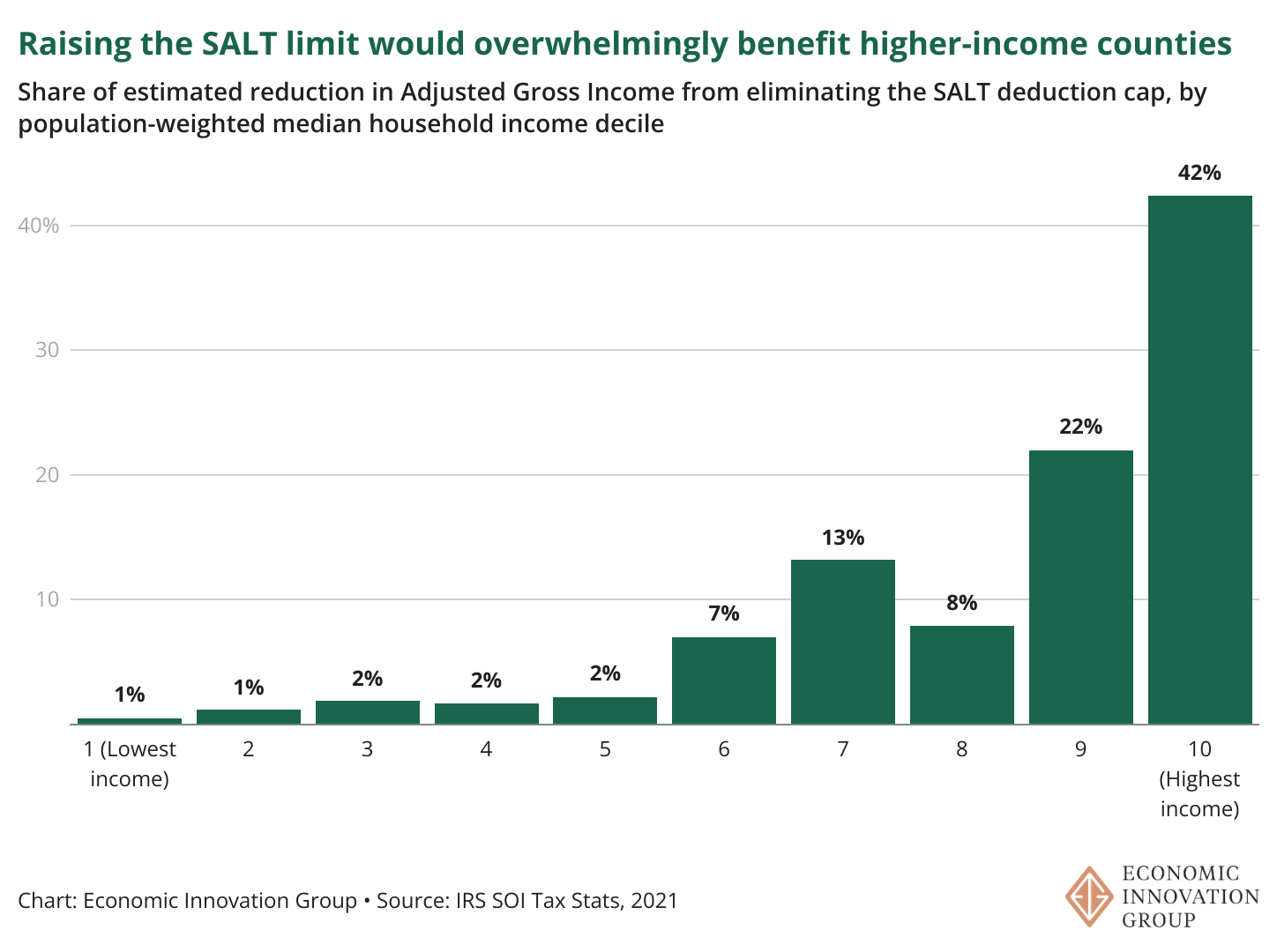

Raising the SALT deduction cap would be even more tilted against low-income, pro-Trump, and rural counties.

Proposals to raise or eliminate the cap on the SALT deduction would tilt its benefits even further away from the Republican coalition and distressed places.

If the cap on the SALT deduction were eliminated, rather than kept at its current level of $10,000, 87 percent of the benefits would go to taxpayers in counties won by Kamala Harris last November. Virtually none would go to the places that formed the backbone of President Trump’s winning coalition.

Eliminating the SALT deduction’s cap would furthermore do nothing to cut taxes for those living in the lowest-income parts of the country. In fact, it would tilt the deduction even more towards prosperous communities. Less than one-tenth of the expanded deduction would benefit communities in the bottom half of the income distribution.

Finally, eliminating the SALT cap would yield meager benefits to rural communities. An outright majority of the benefits would go to large urban counties. Rural counties, meanwhile, would see a mere one percent of the benefits from eliminating the SALT deduction’s cap, despite accounting for 13 percent of the country’s population.

Methodology

Estimates in this blog are based on IRS SOI tax stats from 2021, the most recent available data. Taxpayers are assigned to counties and eight different income buckets. Within each unique county-income bucket, the IRS provides the total number of tax returns and the aggregate value of state and local taxes reported. The IRS also reports the number of taxpayers taking the SALT deduction and the combined value of such deductions.

The estimates of SALT reform’s benefits to particular places are measured in changes to Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) since the data does not allow us to apply individuals’ specific federal marginal tax rates to such changes. All references to benefits in these estimates are to changes in AGI, not fiscal impact.

To estimate benefits by geography from eliminating the cap, we calculate the average state and local tax burden in each county-income bucket, subtract $10,000 to reflect the current cap, and then multiply the excess state and local tax payments (which would be fully deductible) by the number of taxpayers in each bucket. These estimates are then aggregated according to population weighted deciles of 2024 county-level Trump vote share and 2018-2022 median household income, as well as EIG’s county-level geographic typology.

We weigh Trump's vote share and median household income deciles by population throughout this analysis. This is due to the highly skewed distribution of county population sizes. There are a little more than 3,100 counties in the United States. More than 2,000 are home to 50,0000 people or less. Weighing deciles by population gives us a more representative picture of the SALT deduction’s effects.

Acknowledgments: Big shoutouts to Ernie Tedeschi of the Yale Budget Lab for advice on the methodology for this analysis and Jiaxin He for data help.