How many jobs were lost to the China Shock?

How much does the United States redistribute income relative to other rich countries?

Do American workers really care if their jobs are meaningful and interesting — and what chance do they have of finding such jobs?

Every guest essay published by EIG as part of its American Worker Project contained at least one surprising or remarkable finding about the U.S. labor market. But we also know that some of you, shockingly, may not have read all of the essays yet. (Just why you haven’t is between you and your guilty conscience.)

Not to worry! We have rounded up 10 of our favorite things about the U.S. labor market that were unearthed by our guest writers, most of them economists. We present them below, partly to entice you to check out the original essays and partly because we just dig this stuff — and since you are a subscriber of this newsletter, we assume you do too.

1) The China Shock did not result in net job losses for the American economy.

As explained by economist Kyle Handley, it’s necessary to look beyond just the immediate, direct effect of the China Shock on manufacturing.

The employment losses were locally concentrated, leading to devastating outcomes for a number of factory towns and their workers. But many of the same companies that shut down their factories in response to the China Shock also adapted and managed to stay in business, often thriving. They not only shifted their activities away from manufacturing and into design and services but also reallocated employees to new workplaces within the same firm.

Handley writes:

First, while about half of the job destruction from the China Shock is from plant closure, surviving plants have positive net job creation.

Second, the negative manufacturing employment effects from Chinese import competition can be decomposed into firm adjustment margins. About 40 percent of the relative effect is from plant industry switching: continuing plants that switch their primary activity from manufacturing to services. This employment switching shift is oriented almost exclusively away from hard hit durable goods sectors towards the service sectors in research, design, management, and wholesale, but would otherwise appear as manufacturing jobs loss in public-use aggregated regional employment data.

Third, most job destruction in manufacturing in response to the China Shock occurs within firms that are contemporaneously expanding services employment. This factor, plus industry switching, drives positive overall net job creation in services such that overall employment is unaffected by the shock, as the job gains in services offset losses in manufacturing.

2) By one measure, wage inequality peaked in the United States more than a decade ago and has been declining since. The same rough trend applies to most OECD countries.

Jacob Kirkegaard writes:

Wage inequality metrics… show high U.S. levels of wage inequality relative to other high income large OECD members — but they also show a noticeably declining trend in recent years. This is illustrated by the interdecile wage ratio, which is the ratio given by dividing the 90th percentile wage by the 10th percentile wage, in Figure 8.

3) The American tax-and-transfer system is no less redistributive than the typical rich country’s.

This finding comes via the same Kirkegaard essay. Post-tax, post-transfer income inequality remains elevated here because America has higher market inequality — i.e. before taxes and transfers are taken into account.

4) Work continues to untether from the workplace.

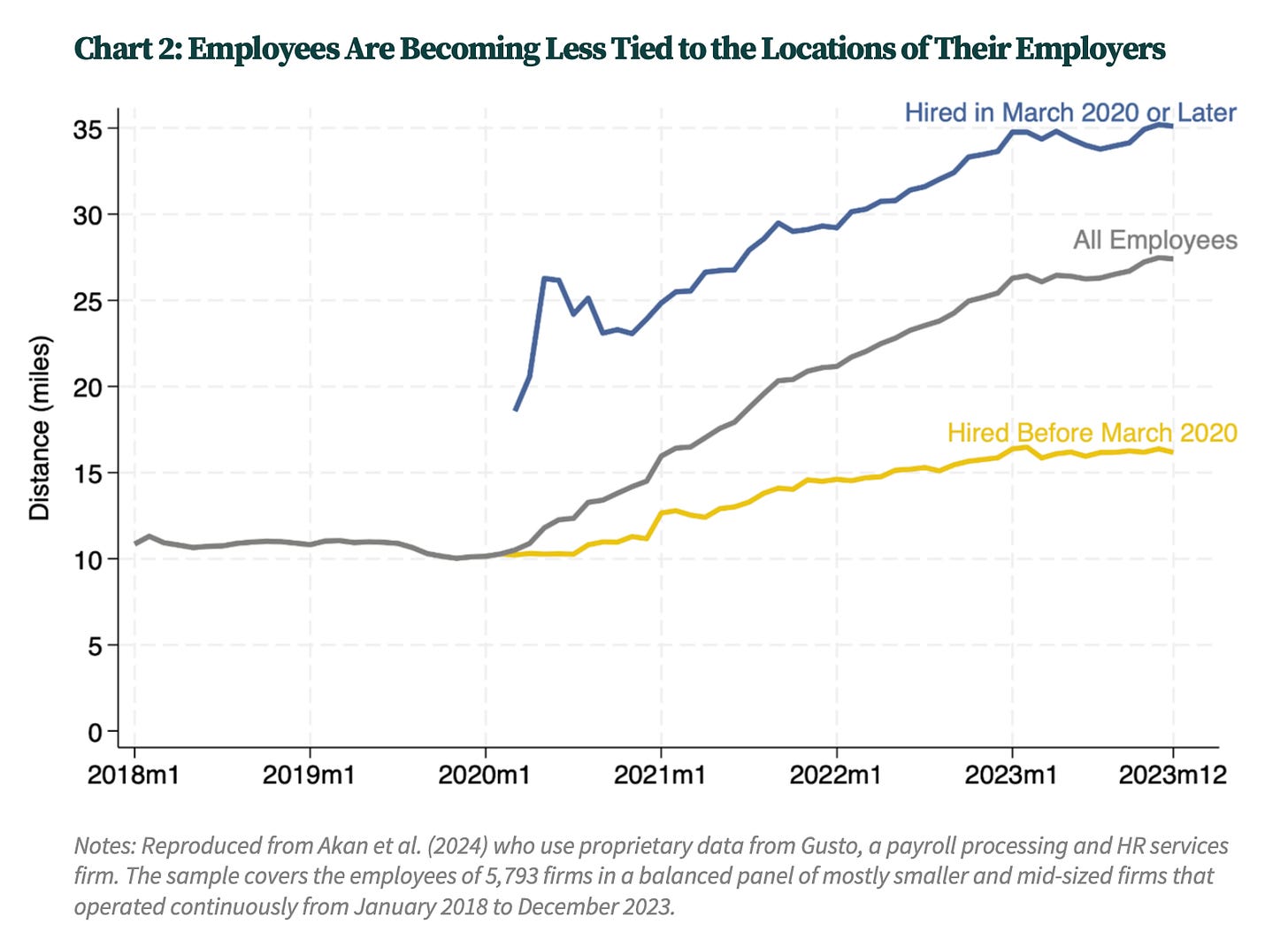

Work-from-home was not a temporary Covid trend destined to reverse, at least not fully. The trend of workers living more distant from their offices has continued, says Stephen Davis:

Have people responded to the rise of WFH by living farther from their employers? In a recent analysis, my coauthors and I provide evidence on this score, reproduced here as Chart 2. We analyze employee-level data at 5,800 firms that operated continuously from 2018 to 2023. As of 2019, just 1 percent of employees at these firms resided more than 50 miles from their employer’s worksite. Among employees at these firms hired since March 2020, more than 7 percent live more than 50 miles away from the employer’s worksite as of 2023.

5) A growing share of American workers find their jobs interesting and meaningful.

For example, the percentage who strongly agree that their job is helpful for other people rose from 27 percent in 1989 to 47 percent in 2015. The analogous figures for having a job that is useful to society are 26 percent and 40 percent. These are substantial changes worthy of further investigation, as they suggest that workers increasingly appreciate jobs that offer more than just good pay and varied benefits, but also a sense of purpose and meaning.

6) Adjusted for inflation, compensation for workers in the bottom 20 percent has grown — and much faster for women than for men, shrinking the gender gap in this bottom quintile.

These findings are from Scott Winship:

7) The rise of app-based work is real — but only for drivers, not the broader labor market.

This conclusion belongs to Andrew Garin. Based on his research with coauthors Dmitri Koustas and Emilie Jackson, Garin writes that “the number of workers with payments from online gig economy apps rose dramatically beginning in 2014.”

But, Garin continues:

First, the rise has been entirely driven by driving-based platforms, namely ridesharing and delivery platforms such as Uber, Lyft, and Doordash. In the rest of the labor market, platform-based gig work aside from driving remains extremely rare.

Second, the typical annual earnings from platform work are quite small: Most participants make less than $2,500 per year, a large portion of which goes to expenses like gas and car maintenance. That’s because most participants only work intermittently on platforms during the year, and in most cases such work supplements another traditional job that is their main source of annual income. Platform earnings are a primary income source for only about one-fourth of people who do any platform-based work at some point during the year, many of whom only work part-time.

Third, outside of app-based driving, there has been no increase in the prevalence of any other type of freelance work reported to the IRS since 2005—well before the advent of smartphones. The emergence of rideshare apps has not heralded a broader labor-market shift towards gig work—it is the only such shift.

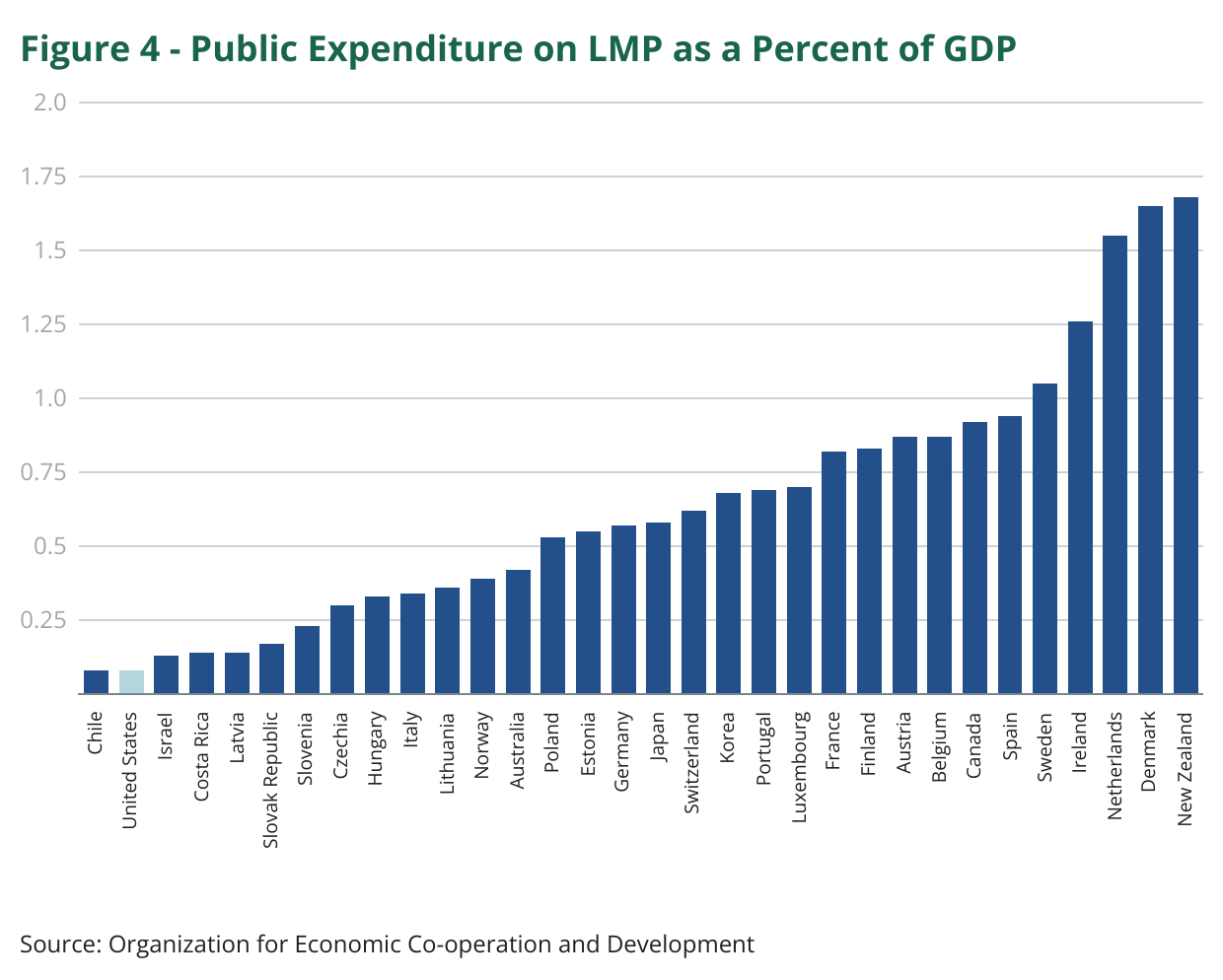

8) The United States has one of the most flexible labor markets among advanced economies — and one of the least supportive.

Within the OECD, the U.S. has one of the lowest ratios of its minimum wage relative to its median wage; the second lowest union bargaining power; the lowest labor market regulation; and among the least generous disability and unemployment insurance systems. And yet the United States still ranks toward the bottom of the OECD in the employment rate for prime age workers…

In addition, active labor market policies that help directly prepare people for jobs and also connect them to jobs should play an important role. The United States currently is a substantial laggard in the area, spending only 0.1 percent of GDP on such programs—about a twentieth of what Denmark spends, as shown in Figure 4.

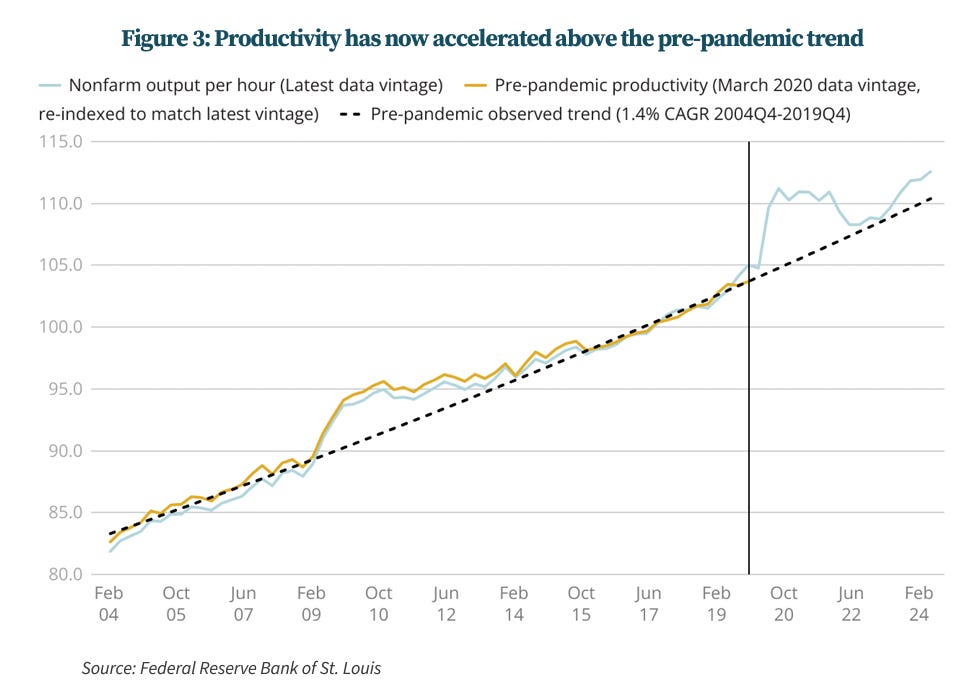

9) Productivity is above its pre-pandemic long-term trend.

Chart via Skanda Amarnath, who adds:

A faster recovery has accelerated the timeline by which the American worker can accumulate experience and human capital, and translate it into productive output. To the extent this experience is also forming within superior matches between workers and employers, the productivity gains could potentially prove larger and more sustained.

10) The racial entrepreneurship gap is shrinking — a trend that accelerated during the pandemic.

Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins writes:

There is mounting evidence that the unique circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed to disproportionately high growth in new Black-owned businesses. Webhosting platform GoDaddy.com publishes data on new microbusiness formation. They showed that between March 2020 and July 2021, 26 percent of new microbusinesses in the US were created by Black Americans. Prior to March 2020, their share was 15 percent.

Other research published in a National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper used state-level data on business registrations to show higher startup rates in Black neighborhoods from 2019 to 2020, particularly in high-income Black neighborhoods. Importantly, this research points to one likely explanation for the surge: stimulus checks issued in response to the COVID-19-related economic downturn were likely associated with the flood of new business formation.