The indicators that’ll really signal a manufacturing renaissance

Leave aside the most recent jobs report, which showed a slight decline in manufacturing employment in December. Leave aside, even, the last eight months of jobs reports, in which manufacturing employment has fallen in every single one.

Slower burn indicators will be the ones to truly signal if and when a manufacturing renaissance takes hold — or if the sector fails to take off.

Which indicators? Those of economic dynamism: measures of the health, vitality, and innovative intensity of manufacturing (or any other sector). These indicators probe well under the surface of the net changes that grab the headlines.

Dynamism may sound abstract, but it captures the very real ebbs and flows of workers and firms in the economy as some businesses start and grow while others contract and disappear. Healthy sectors and economies are competitive, changeful, and constantly churning.

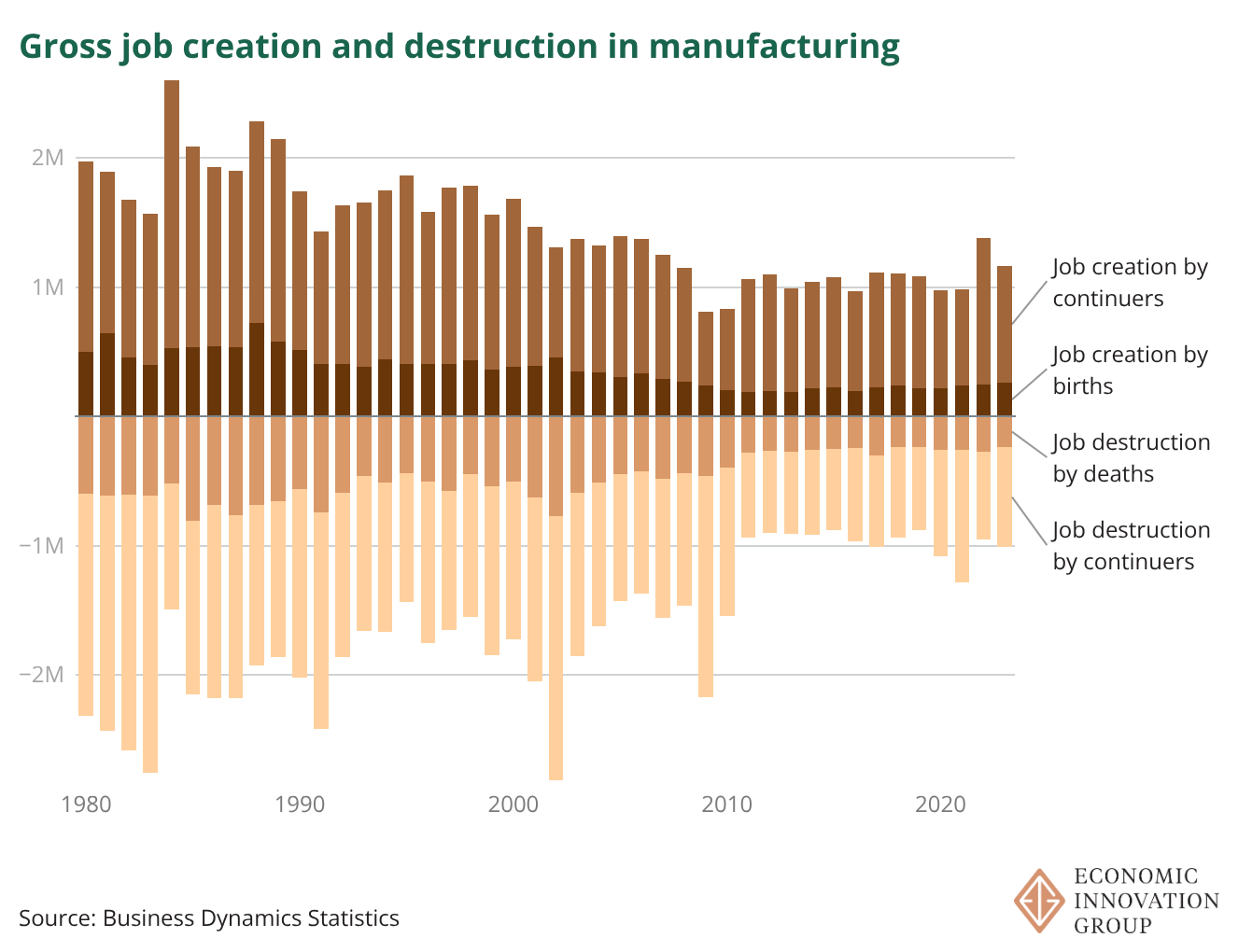

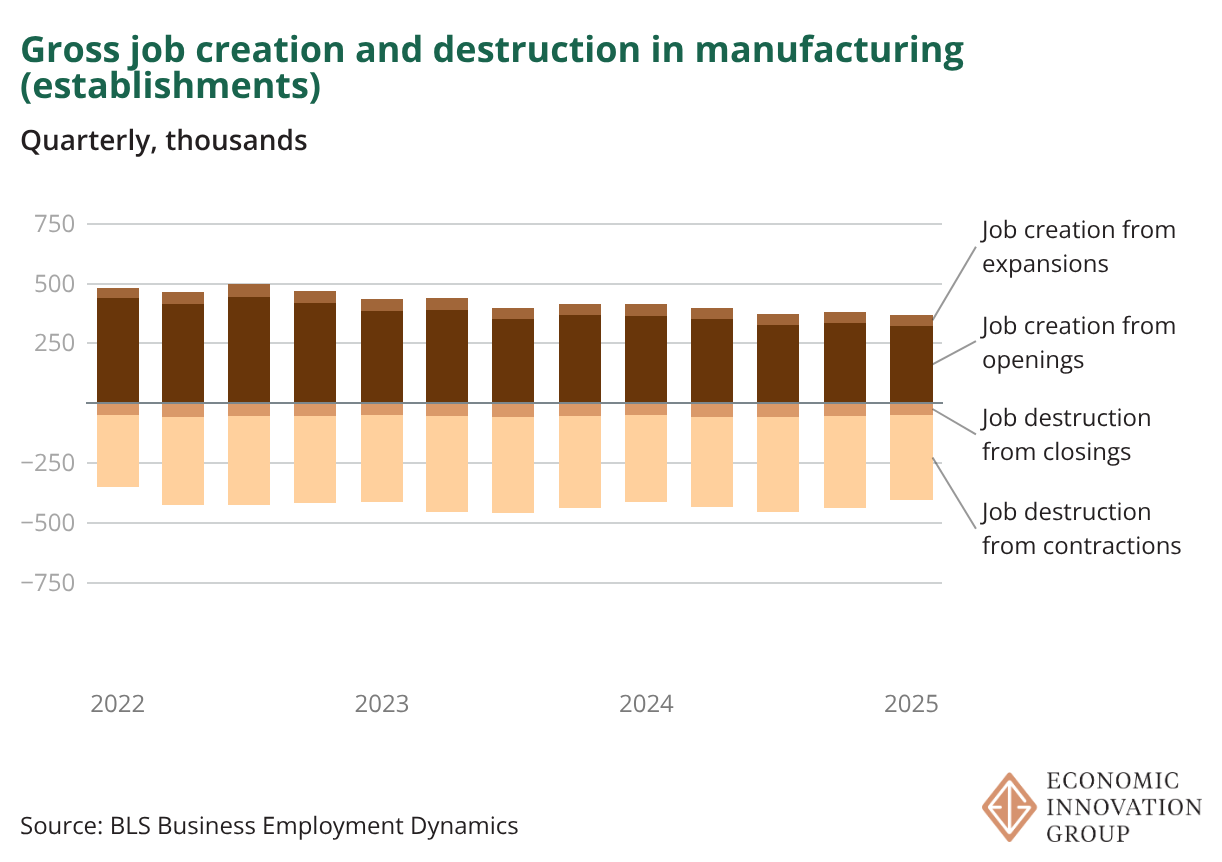

Dynamism in manufacturing has been essentially moribund for nearly 15 years, as evidenced in this chart of gross job creation and destruction in the sector.

The gold-standard data from the Census Bureau visualized above show that underneath surface-level stability in manufacturing lies a stasis that has reigned for a decade and a half.

Since the Great Recession, manufacturing firms have created 37 percent fewer jobs in gross terms and on average annually than they did in the 1990s, and 22 percent fewer than they did in the 2000s. The slightly positive net change registered most years in the post-2010 era comes from gross job destruction having fallen by even more — by 43 percent on average each year.

The sector stopped hemorrhaging jobs by 2008, which is good. But it never ramped back up creating them, which would have been better.

It came close in 2022, the apex of the post-pandemic stimulus period that included major inducements to manufacture new products such as electric vehicles, clean energy assets, and personal protective equipment in the United States. Even that moment now looks like it might have been a blip rather than a trend break, however. By 2023, gross job creation fell back slightly (although it remains elevated relative to the pre-pandemic period).

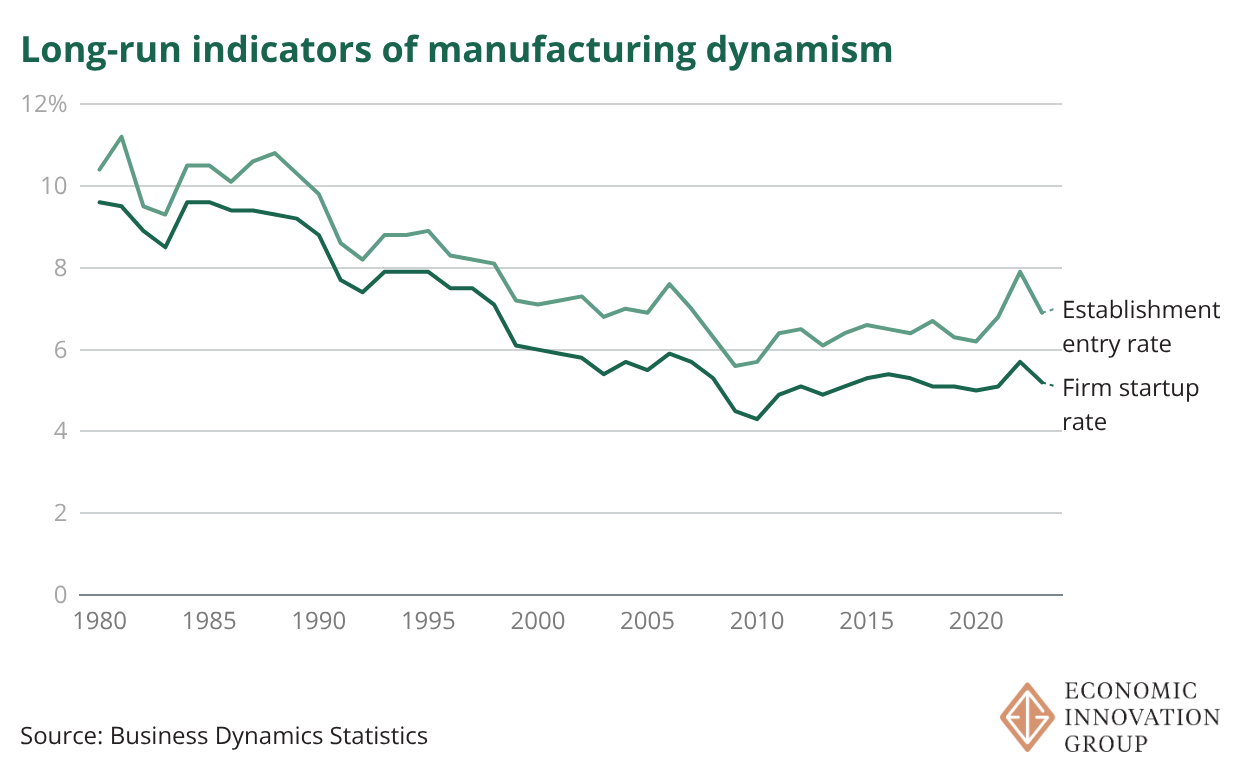

Similar patterns can be seen across other measures of dynamism. The startup rate, which captures wholly new manufacturing firms being launched, reached a post-2008 peak in 2022 but also fell back in 2023. Same for the establishment opening rate, which includes new plants of existing firms, too. Both clear the low bar of looking better than they have in a long time, but neither suggests a renaissance is in the works.

What about Liberation Day, you ask? Contemporaneous indicators suggest that not only did it fail to shake manufacturing out of its slumber but also that it might have made manufacturing even more somnolent.

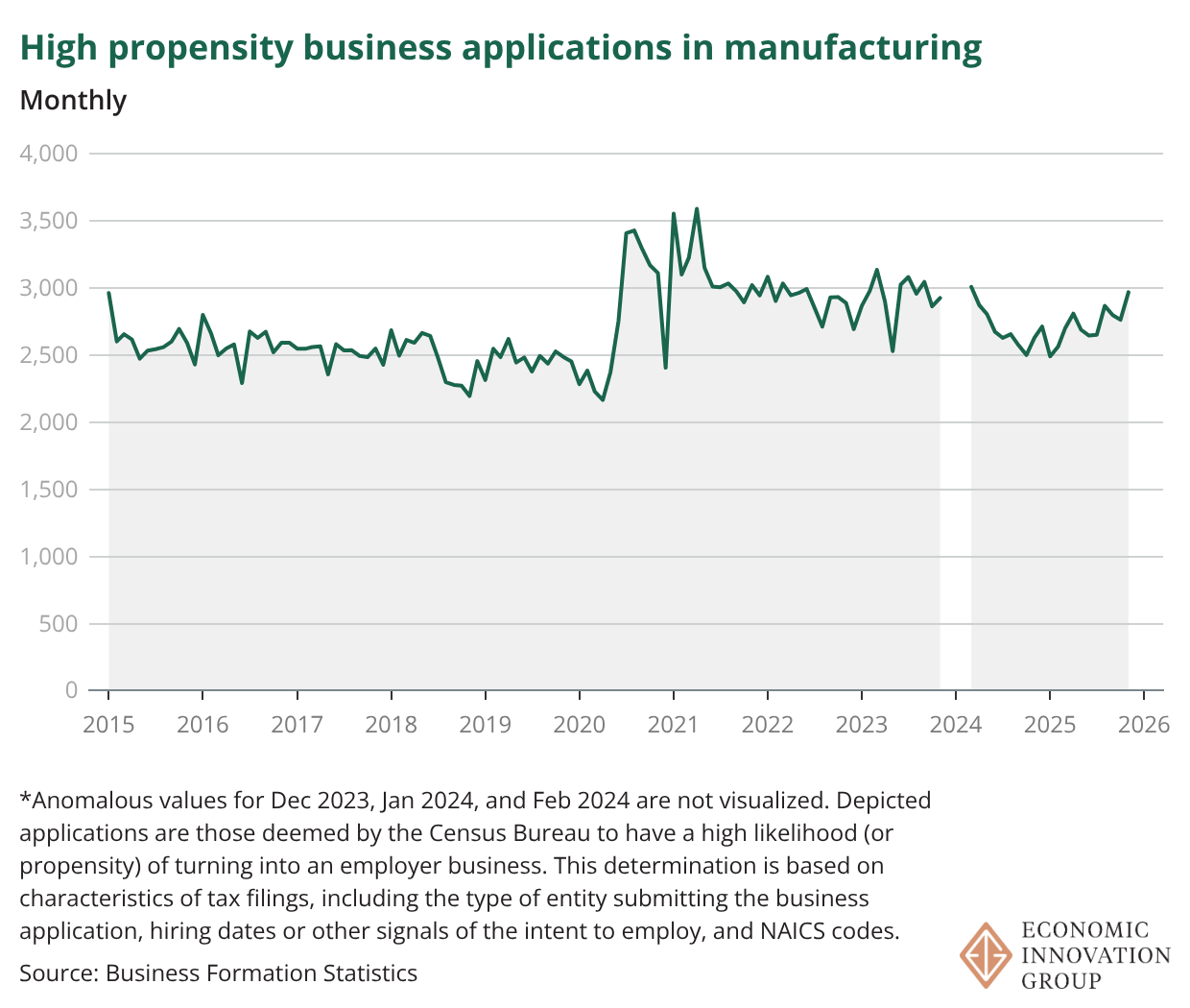

The most promising indicator is, alas, also the hardest to interpret: new business applications.

Filings for new manufacturing EIN numbers that bear the hallmarks of genuinely new firms intending to hire workers decreased in 2024 but climbed steadily in 2025, ending the year back at 2022 levels.

However, these administrative data serve as useful early-stage indicators of entrepreneurial intent and also move with uncertainty. New manufacturing EINs might be filed in response to tax or other policy changes (check yes for 2025), in response to changes in corporate organization or legal structure (which tariffs could feasibly have precipitated, so check), or in response to genuinely new business opportunities (check?). Census does its best to identify the applications that are most likely to transition into employer businesses — the “high propensity” business applications we show here — but just as during the throes of the pandemic, it’s difficult to say what exactly might be driving the numbers in 2025.

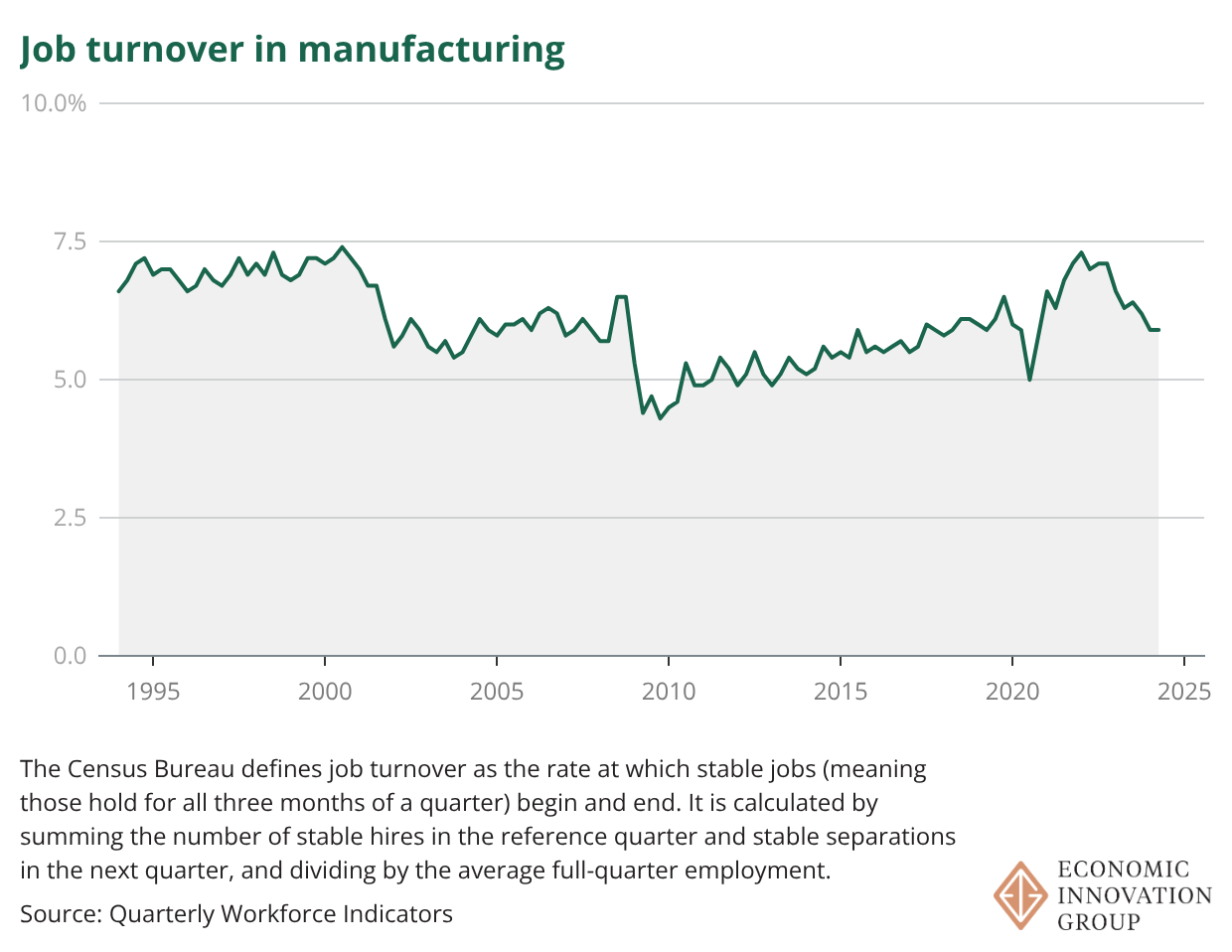

Back in the labor market, job turnover rates from BLS’ Quarterly Workforce Indicators run only through Q2 2024 but follow a pattern of recent decline associated with recessions, not expansions. Here, the southern turn started in 2022, consistent with manufacturing’s post-pandemic rebound peaking then before losing steam.

Replicating our opening graphic for quarterly establishment-level data from BLS’s Business Employment Dynamics through Q1 2025, we see that gross job creation by opening and expanding establishments has fallen steadily since Q3 2022, as well.

None of this signals an incipient renaissance in American manufacturing. Post-pandemic greenshoots already started withering in 2022, and they look no more invigorated now, as we head into the second year of Trump’s second term. Indeed, the latest ISM figures suggest the sector has been in modest retreat for around a year. The monthly job numbers also show manufacturing employment has been contracting, on net, continuously since late 2023.

Dynamism — entrepreneurship, innovation, competition — is what delivers enduring advantage. Neither the incumbent-friendly subsidies of the Biden years nor the cost-raising, protectionist tools of the Trump approach appear to have been effective in rekindling it in American manufacturing.

How much dynamism can we expect in manufacturing? Capital-intensive sectors are by nature less changeful than capital light-sectors, given the cost and timelines involved in setting up production. It’s a bigger leap to set up a manufacturing plant than a taco stand. And to be sure, many American manufacturers are wildly inventive. Some creative destruction that in prior eras might have happened between firms could now be internalized within a single firm’s boundaries. But others have outsourced dynamism — still capturing profits, for now, after having relocated the very engines that propel the industry forward off American shores.

U.S. manufacturing as a whole looks static and far less dynamic than its potential. Your friends at EIG confidently posit that the country will not durably reindustrialize without reinvigorating dynamism sector-wide and at scale.

The second piece in this series will explore the geography of manufacturing dynamism, too, because modern visions of an industrial renaissance are printed from the negatives of the communities manufacturing left behind. Where new activity is taking root can tell us a lot about whether simple cost considerations are powering modern American manufacturing, or whether the sector is being fueled by a fire much deeper and more powerful. Stay tuned.

The St. Louis Fed graph indicates that labor relative to capital has not participated in the productivity gains over the past years.

It was not all that long ago that the manufacturing sector was responsible for its highest capital investments in decades. Those investments did not necessarily result in net job creation, but they seemed to reflect confidence in the national economy. But then the current administration decided to pull the plug on incentives and support for green energy, EVs, etc. Now other countries like China are dominating these markets.