All Quiet on the AI Front

New analysis finds no clear signs of disruption…yet.

High unemployment rates for recent college graduates and the slow hiring of tech workers have raised alarm bells about whether AI is already, today, disrupting the labor market.1

We have just published our own comprehensive study of the effects of AI on jobs, in which we make two novel contributions.

We look at its possible effects not just on employment, but on other indicators like workers switching jobs or exiting the labor force entirely.

We don’t just conduct our analyses using a single measure of occupational exposure to AI. We use five different measures drawn from four different research papers.2 This approach is tremendously useful because each measure has a different methodology for identifying which workers are exposed to AI, and by how much. Any conclusion about the effects of AI is thus more persuasive if it is consistent across all five measures.

Below we present how one of the analyses looks when using all five measures of AI exposure, demonstrating their overwhelming consistency and one small way in which two measures diverge from the others.

———————————

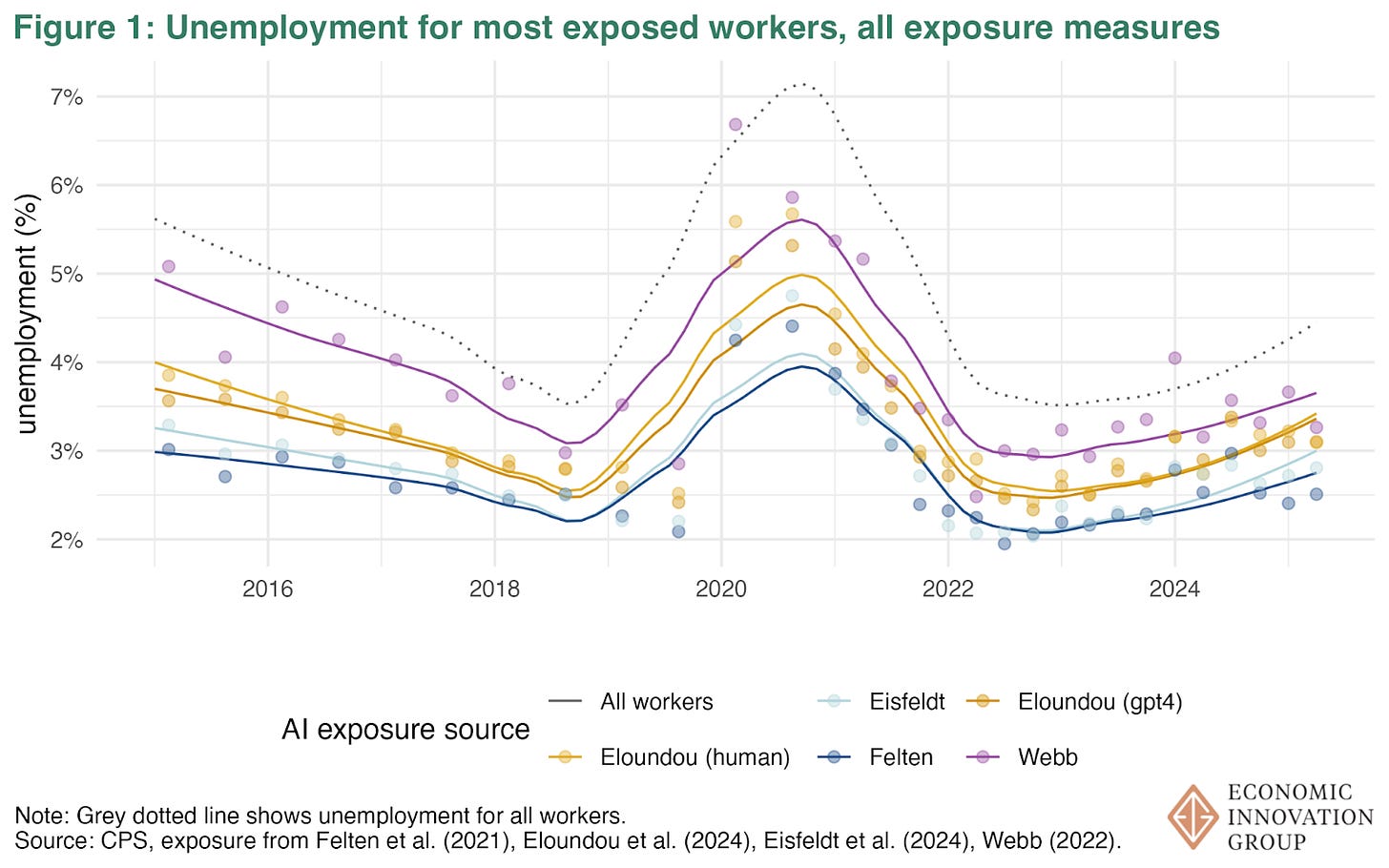

One of the most basic indicators we consider is the unemployment rates of the most AI-exposed workers over time, shown in Figure 1 below.

The bottom line: There is no visible effect of AI on unemployment. The most AI-exposed workers tend to have lower unemployment rates than the average worker, but the trends look very similar. Unemployment rates are rising for both workers very exposed to AI and those that are not.

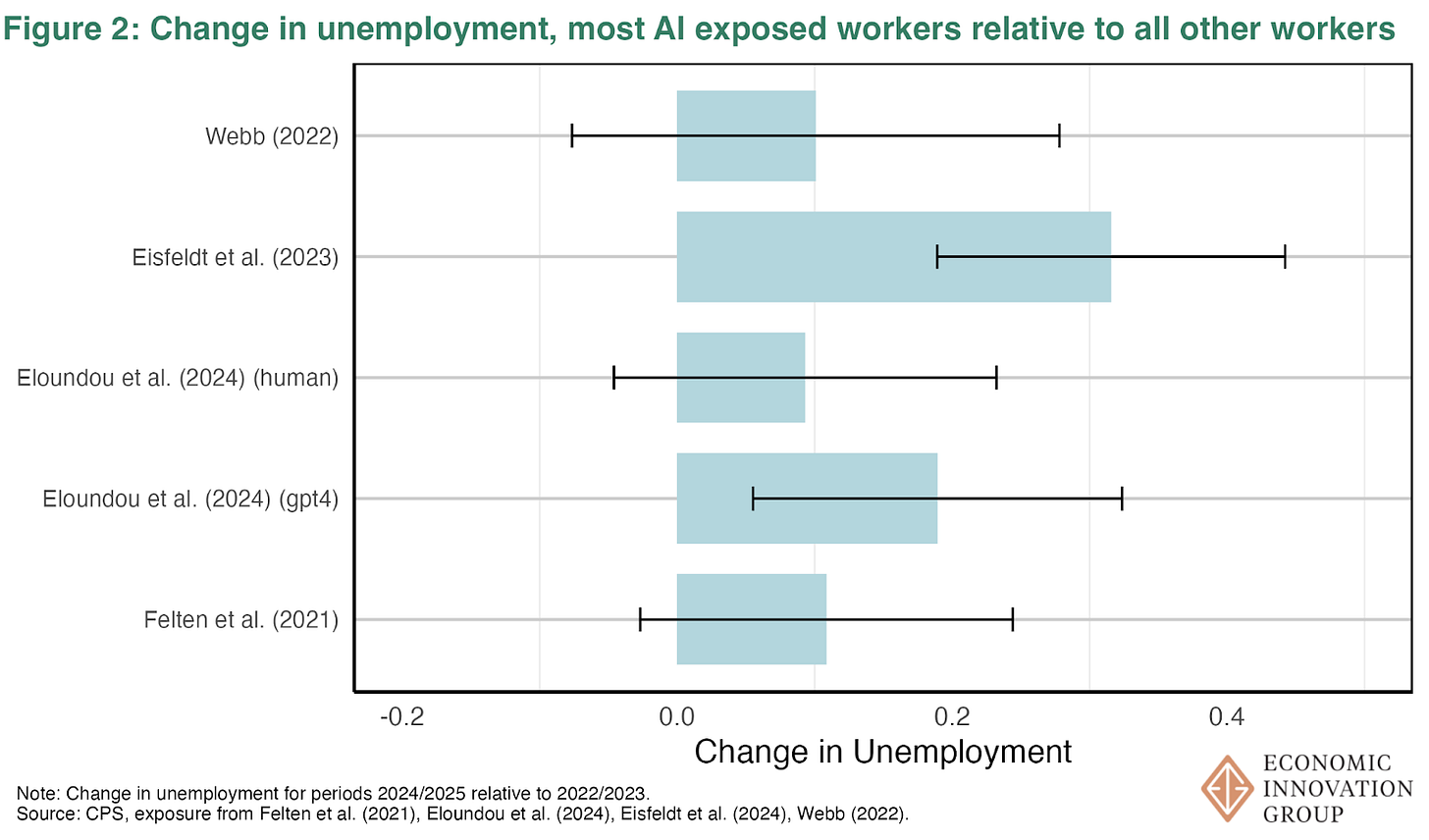

Rather than relying on eyeball econometrics, we can do one better by estimating whether the unemployment rate for the most AI-exposed workers is rising faster in recent years than for everyone else.

The results from that are shown in Figure 2. Three of the five measures show no statistically significant difference. For those, we cannot say with any degree of confidence (95 percent confidence to be exact) that unemployment rose faster for the most AI-exposed.

Two of the measures, however, do show an exceedingly modest 0.2 to 0.3 percentage point relative increase among the most AI-exposed. Interestingly, these two measures, unlike the others, were actually generated by AI — specifically GPT-4 for Eloundou et al. and GPT 3.5 Turbo for Eisfeldt et al. So if anything, AI itself is telling us that AI-exposed worker unemployment was rising faster. But again, even for these two measures the relative increase is slight.

Beyond unemployment rates, we also find that AI-exposed workers were not more likely to exit the labor force or switch occupations, nor that firms were detectably altering how they assign tasks to workers based on AI’s capabilities. No matter which measure we use or which labor market outcome we look at, we just don’t see AI causing dramatic upheaval in the labor market.

Check out the full study for all of our analyses and conclusions. You can also see our data, sources, and methodology at our Github.

For example see “Educated but unemployed, a rising reality for US college grads” (Oxford Economics) and “The ‘Great Hesitation’ That’s Making It Harder to Get a Tech Job” (Wall Street Journal)

What these measures fundamentally do is look at the overlap between what AI can do and the types of tasks different types of workers do.

Does the unemployment variable utilized include those that were employed and were let go or does it includes those actively looking for a job? If #2, can you distinguish recent grads? Look forward to reading the full report!