If international students don’t get H-1Bs, IT outsourcers will

The pathway through which some of the most skilled and productive workers enter the American labor force may soon become much narrower — and employees of IT outsourcing firms are poised to take their place.

The Trump administration is weighing whether to eliminate or severely scale back the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program, which allows international student visa (F-1) holders to work in the United States after graduating.

OPT is a policy that allows foreign nationals educated in American universities to establish a foothold in the labor market. The program grants STEM degree holders three years of post-graduate employment and is commonly used as a stepping stone for obtaining the H-1B visa, which is used for skilled workers.

While the skilled immigration system needs reform, eliminating OPT is misguided if the objective is to make H-1Bs available to the most highly skilled applicants with the greatest earning potential. Our analysis finds that individuals on student visas, including OPT recipients, represent some of the most economically productive H-1B applicants and are among the least likely to be employed by the outsourcing firms often criticized for abusing the H-1B program.

H-1B recipients who previously held F-1 student visas:

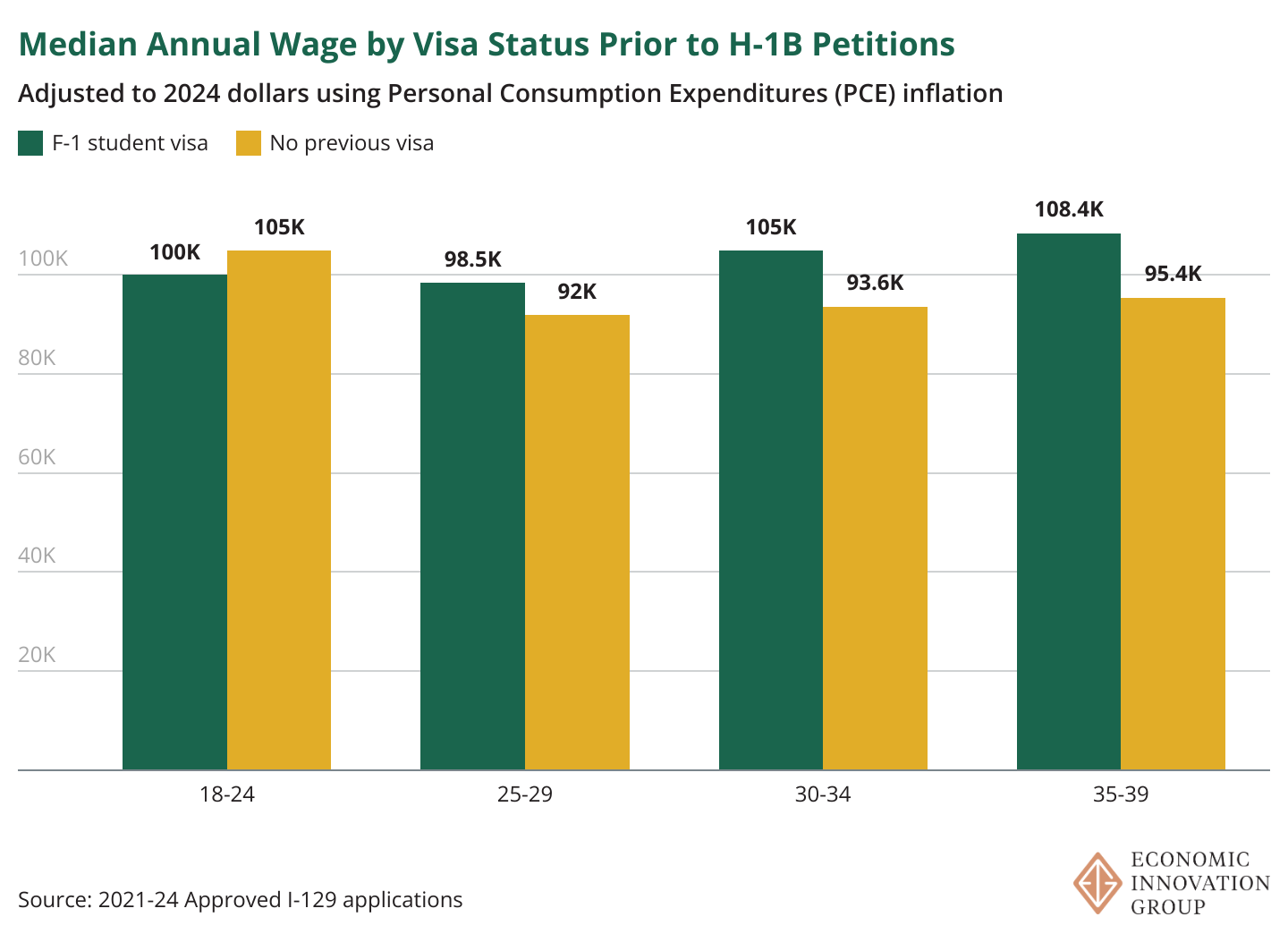

Earn 6.3 percent higher median wages than recipients who come directly from abroad, reflecting better labor-market matching and stronger skills acquired through their American education.

Earn 11.0 percent more within the tech sector than workers recruited directly from overseas. This is largely because the notorious IT outsourcing firms primarily recruit workers directly from overseas — not former international students.

Earn 14.1 percent more over the course of the H-1B’s duration, as they are on average six years younger than recipients without prior visa status and therefore experience faster expected wage growth.

Earn $1 million more over a lifetime on average in net present value terms than recipients without prior visa status.

These findings underscore that foreign-born students educated in American universities are among the most skilled and highest-paid H-1B holders. Restricting their pathways would weaken the program’s outcomes, not strengthen them.

International students are unlikely to work for IT outsourcing companies after graduation

While the outsourcing of software services to countries with lower labor costs has been well documented, a less recognized practice involves foreign tech companies establishing American subsidiaries that employ lower-wage workers to perform comparable tasks domestically. These are referred to as “outsourcing companies,” “outsourcing firms,” or, simply, “outsourcers.”

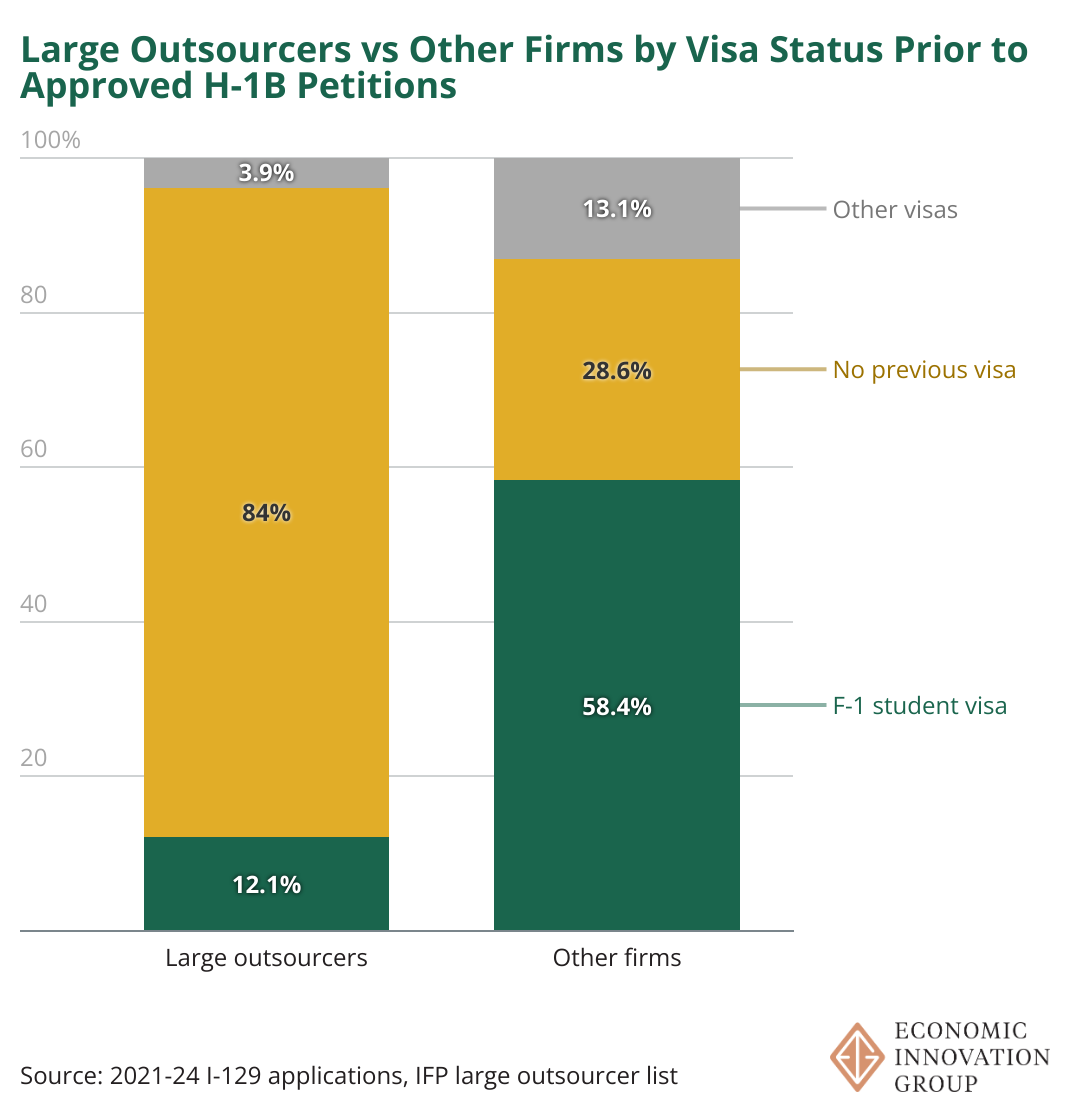

According to our analysis, which uses H-1B lottery data from FY 2021-2024 retrieved by Bloomberg, only 12 percent of H-1B recipients at the large outsourcing firms are people who were initially on the F-1 visa for international students. On the other hand, 84 percent of H-1Bs working at these firms had no prior U.S. visa status — meaning they were recruited straight from abroad.

At the firm level, the difference in skill between former F-1 holders and H-1B recipients coming directly from overseas is stark. In fact, H-1B recipients at non-outsourcer firms who transitioned from F-1 visas earn 8.8 percent more than foreign workers at outsourcers entering the program directly from overseas.

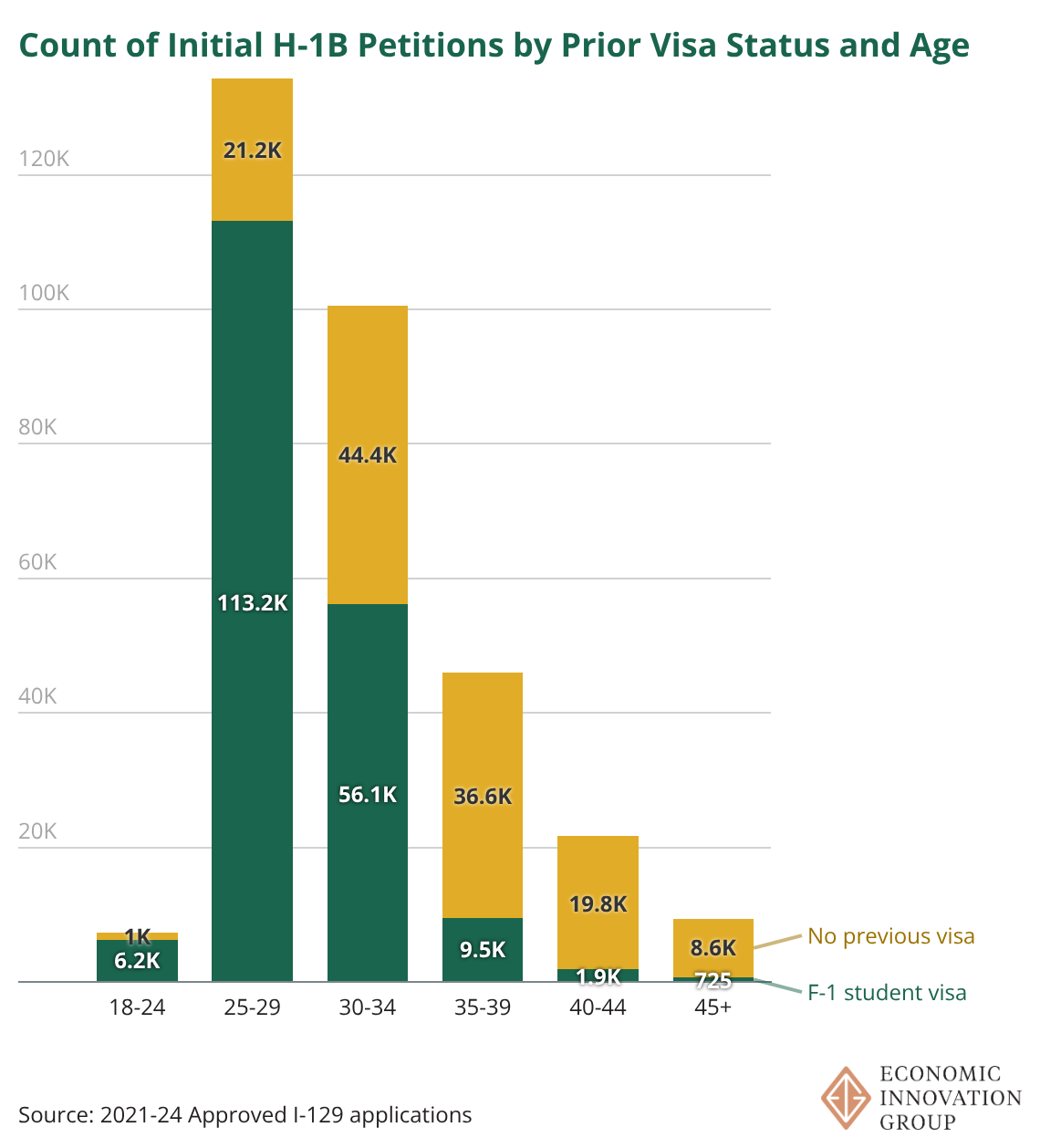

As the above figure shows, 98.6 percent of international students applying for H-1Bs are under the age of 40. We therefore restrict the comparison between former F-1 holders and applicants with no prior visa to this range, excluding the outliers of international students pursuing mid- or late-career degrees.1

Aside from the youngest cohort, median wages for F-1 students petitioning for H-1Bs rise steadily with age, while wages for applicants without prior visa status remain largely flat. (Only about 1,000 H-1B recipients aged 18–24 applied directly from abroad, and their wages exceed those of F-1 holders, likely reflecting higher sponsorship thresholds for foreign-educated recent college graduates.)

Among workers ages 25 to 29, former F-1 students earn 7.1 percent more than those without previous visas. The gap widens to 12.2 percent for ages 30 to 34 and 13.6 percent for ages 35 to 39.

This upward slope for the American-educated applicants reflects normal labor-market dynamics, in which wages increase with experience and educational attainment. By contrast, the stagnation in wages across age bins for applicants coming directly from abroad suggests labor-market distortions, driven in part by large outsourcing firms who tend to hire lower-skilled and lower-paid older guest workers that have no prior education or work experience in the U.S.

Replacing the H-1B lottery with a lifetime earnings ranking would retain top international students

Scrapping the H-1B random lottery for a system that favors a lifetime earnings ranking would help retain many more international students who graduated from U.S. colleges and universities.

In June 2024, President Trump said on the All In podcast, “Somebody graduates at the top of the class, they can’t even make a deal with the company because they don’t think they’re going to be able to stay in the country. That is going to end on day one.” Our proposed ranking scheme would bring the immigration system closer to the president’s goal of retaining more top international students who study at American schools. Eliminating OPT would do the opposite.

Under a lifetime earnings ranking, 74 percent of new H-1B awardees would be students transitioning from F-1 visa status, in contrast with 52 percent under the current random lottery. These results reflect that former F-1 holders are generally younger and earn higher wages for their age cohort, giving them better expected lifetime earnings.

The new H-1B fee rule blocks outsourcers — but it has major problems

Because the Trump administration’s $100,000 fee for H-1B applications only impacts the H-1Bs coming from abroad, it is currently having a disproportionate impact on IT outsourcers’ reliance on the program, with many of the firms reportedly filing far fewer petitions. However, the fee rule is already facing two separate lawsuits since its enactment in mid-September.

But even if the fee rule survives legal scrutiny, it remains a crude tool that will also harm H-1Bs coming from abroad who are not employed by outsourcers and who command large salaries. Moreover, IT outsourcers can adapt by transferring their workers from abroad on L-1 visas, then having them apply for H-1Bs while inside the United States to bypass the fee altogether.

Because L-1 visas can only be used for employees of international companies, a scenario in which the fee survives and OPT is eliminated favors IT outsourcers at the expense of American firms — especially startups.

Despite the fee, large IT outsourcing firms will likely continue their widespread abuse of the H-1B program absent other reforms, like a lifetime earnings ranking. If OPT is eliminated or severely curtailed, their prevalence in the H-1B program will be even more pronounced.

Immigration policy should prioritize the skilled workers who most bolster the American economy. Our findings show that international students educated at universities in the United States are the most likely to be sponsored by firms that reward skill.

To ensure that the H-1B program better delivers broad economic gains, the Trump administration should focus on making student-to-worker visa pipelines more favorable to top talent. Cutting OPT could mean handing a larger share of H-1B visas to the very outsourcing firms that the president hopes to rein in.

Including these outliers would skew the numbers even more in favor of F-1 holders.