Looking for the Ladder

Is AI Impacting Entry-level Jobs?

As part of EIG’s American Worker Project, we are delighted to present this guest post from Zanna Iscenko, AI & Economy Lead, Chief Economist's Team, Google; and Fabien Curto Millet, Chief Economist, Google. Click here for a PDF version of this post.

A potent narrative has taken hold in public discourse: that Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly and inexorably eliminating the first rung of the career ladder for young graduates.

This anxiety is reflected in surveys where a majority of recent graduates find the job market challenging and believe AI is reducing the number of entry-level positions in their field. Media headlines and business reports amplify this concern, suggesting a fundamental, technology-driven restructuring of the workforce is not a distant prospect but a present reality — with entry-level, white-collar jobs as the first casualties.

Lending significant academic weight to this narrative is the working paper by Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen (2025), which is aptly titled “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence.”1 Its headline finding is striking: a 16 percent relative decline in employment for early-career workers (ages 22–25) in the most AI-exposed occupations since the widespread release of generative AI in November 2022.

While the current economic challenges of young workers in these fields are palpable and distressing, we believe that this emerging diagnosis is flawed. The most plausible explanation is that the data patterns observed are not early warnings of large-scale technological displacement, but rather the predictable consequences of a classic macroeconomic shock: the sharpest monetary policy tightening cycle in four decades.

Correcting the diagnosis for events to date matters, since viewing the challenges of early career workers through the narrow aperture of AI impacts could lead to overly narrow and inappropriate remedies. This does not mean, naturally, that the professional futures of young workers are safe from technological disruption going forward. Reassurance in the present should not preclude vigilance in the future. We are still in the early innings of the AI transformation, and much could happen — leading us to make recommendations for various variables that should closely be watched as part of any monitoring strategy.

More generally, we find the spotlight that the “Canaries” paper placed on these workers to be absolutely salutary given the profound policy questions that need addressing in areas like education and training.

The Trouble with Timing: Why the AI Displacement Narrative is Premature

The central weakness of the hypothesis that AI is the main driver of the recent entry-level downturn is its implausible timeline.

The “Canaries” paper documents a dramatic inflection point in employment for young, AI-exposed workers beginning in November 2022, immediately following the public release of ChatGPT. By June 2023, almost a half of the total observed employment decline for the occupations the paper showcases as representative of this group, software engineers and customer service workers, had already materialized.

This timeline suggests that within a mere six months of a consumer-facing chatbot’s launch, firms across the economy not only decided that AI could replace junior staff but also managed to implement the necessary technological infrastructure, redesigned complex workflows, ensured robust data security, and executed these staffing changes at a national scale. Such a rapid and widespread operational transformation seems implausible.

The reality of corporate AI adoption is a far slower and more complex process. It requires more than just employee access to a public tool. Meaningful integration that could justify replacing human labor necessitates enterprise-grade solutions that offer security guarantees, application programming interfaces (APIs) for integration into existing systems, and the development of internal expertise for effective deployment. The key tools for such an enterprise-wide shift were not available at the start of this timeline. The OpenAI API, a prerequisite for building custom applications, was only released on March 1, 2023. ChatGPT Enterprise, which sought to offer data privacy and security assurances for corporations, launched only on August 28, 2023.

Furthermore, the generative AI models of late 2022 and early 2023 were marked by significant reliability issues, including “hallucinations” or the fabrication of information. It is highly unlikely that risk-averse corporations would base mass staffing and hiring decisions on such nascent and unproven technology so quickly. Indeed, US Census data shows that even in Q4 2023, fewer than 10 percent of large businesses surveyed were even planning to use AI in the next six months to produce goods or services.2 Fast-forward to the latest data point for Q3 2025 and adoption by large businesses has only climbed to 12 percent.

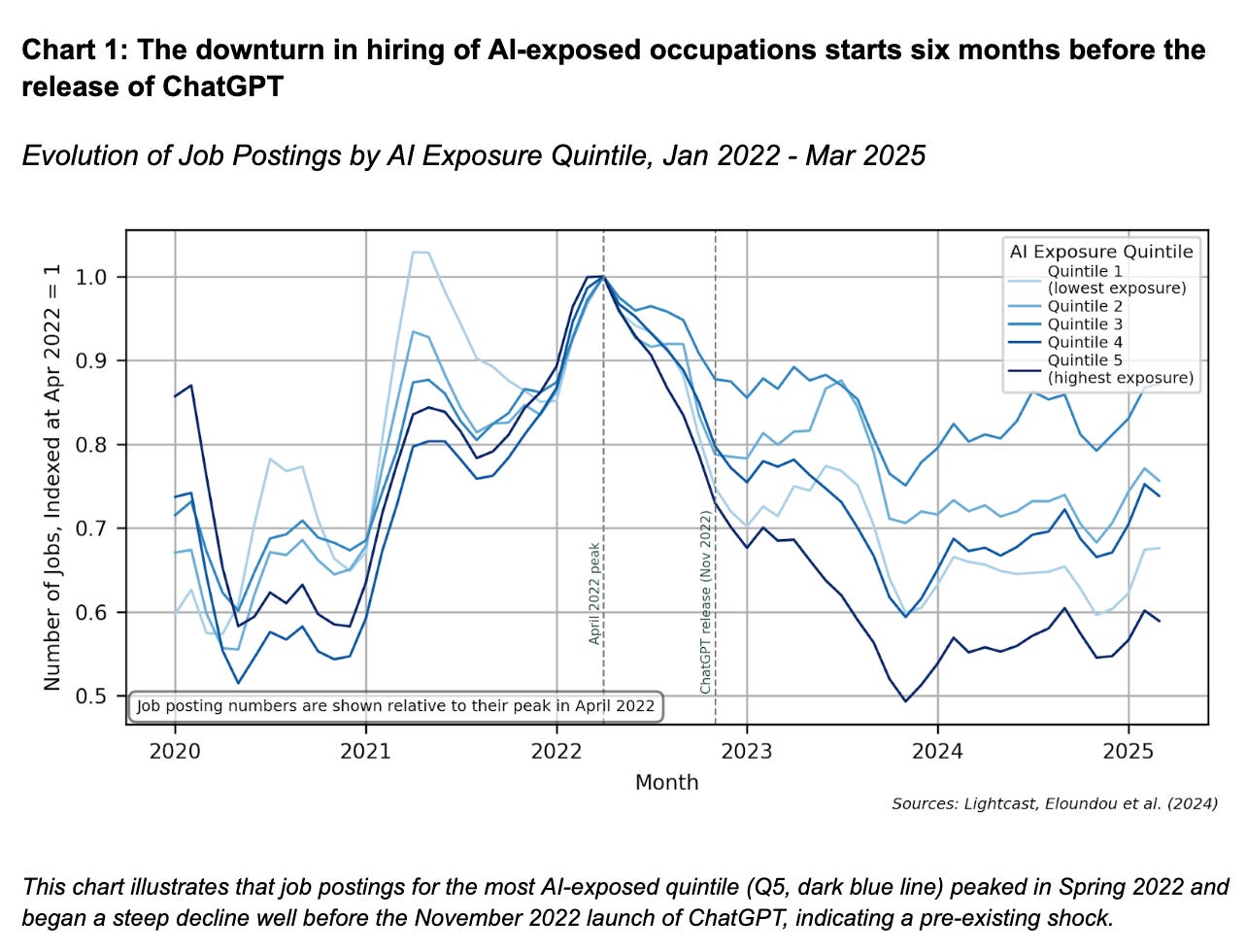

In fact, the downturn in labor demand for AI-exposed occupations — using the same definition of exposure used by the “Canaries” paper3 — began long before ChatGPT’s launch, as shown in Chart 1 above. An analysis of aggregate job postings data from Lightcast reveals that vacancies for the highest AI exposure quintile of occupations peaked in March–April 2022 and declined sharply throughout the remainder of the year.

This hiring slowdown predates any plausible generative AI effect by over six months. The decline in employment levels starting in November 2022 is the natural, lagged consequence of this pre-existing hiring freeze, as routine attrition is no longer being offset by new hires.

This timing mismatch points to a fundamental analytical issue: the focus on a narrow age band (22–25) in the “Canaries” study makes its findings highly sensitive to shifts in hiring inflows. Unlike older cohorts, which, even in the absence of external recruitment, are naturally restocked by younger workers aging into them, the entry-level cohort relies almost entirely on new graduates being hired to maintain its numbers. When that hiring plummets — as it did in early 2022 — the cohort mechanically shrinks.

This effect is particularly pronounced if age groups are defined narrowly. Consider, for instance, a hypothetical professional occupation which starts with an equal number of workers of each age between 22 and 65 and experiences a complete hiring freeze but zero layoffs, across all seniorities, for a year. If we study this occupation a year later we will find that entry-level employment for the 22–25 year-old workers has shrunk by a shocking 25 percent while it remained level for all other age groups.

Even in less extreme circumstances, aging can create the statistical illusion of a targeted decline in the youngest cohort, when the root cause is simply a broad-based hiring reduction across the labor force.

Because the hiring slowdown was steepest in AI-exposed occupations, this mechanical entry-level cohort shrinkage would be most pronounced in that segment of the labor market, perfectly mimicking the pattern that Brynjolfsson et al. attribute to AI-driven replacement.

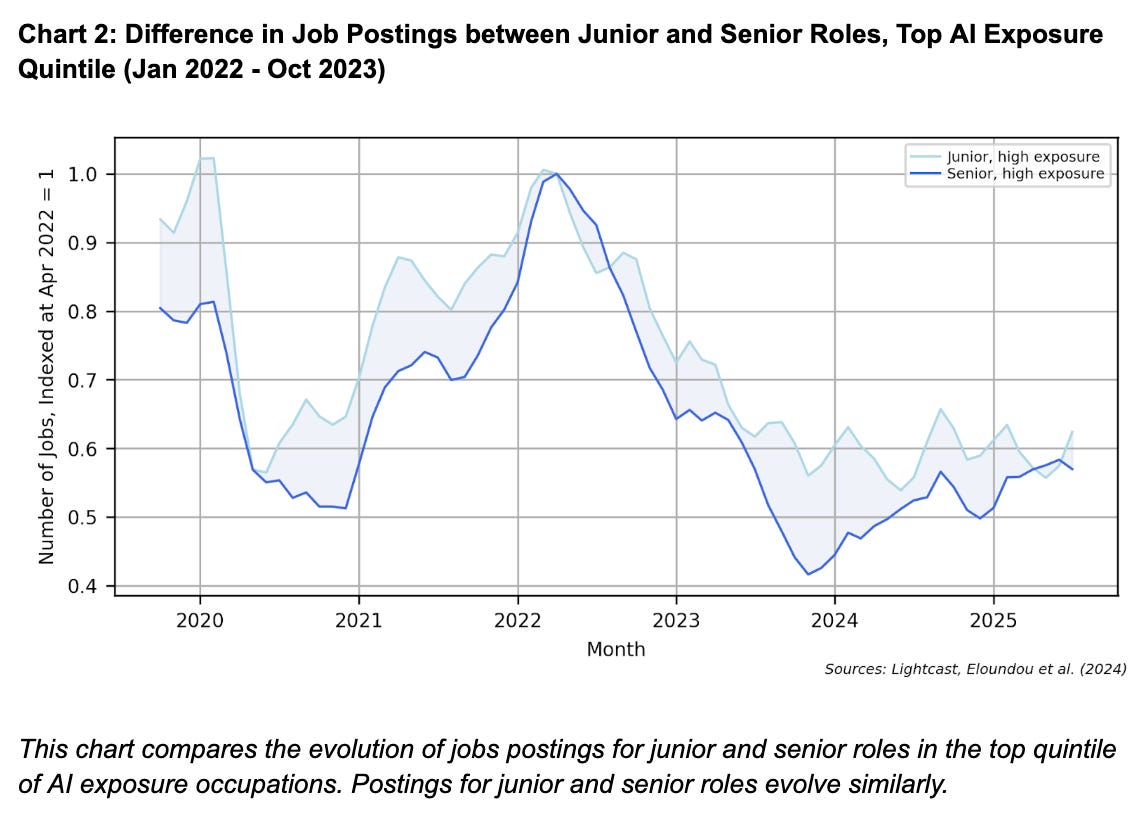

Data on postings supports the “aging” interpretation as well. There is no evidence that job postings for junior roles within occupations most exposed to AI have declined more than postings for senior positions. Postings for both levels of seniority have been falling roughly in parallel since their peak in Spring 2022, with the decline in junior positions stabilizing faster.

An Overlooked Culprit: Monetary Policy and Interest Rate Sensitivity

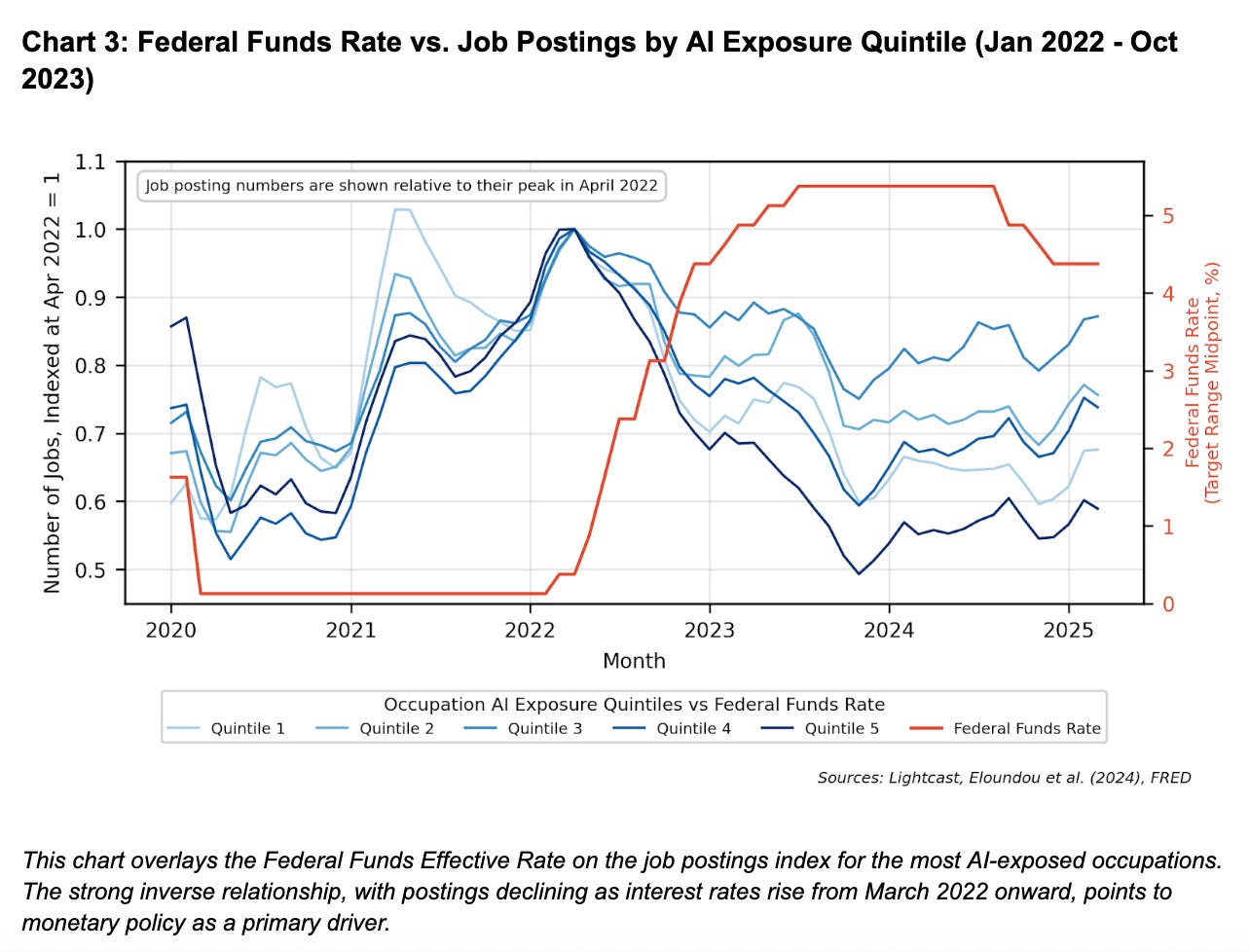

If the AI adoption timeline does not align with the labor market data, what does? The sharp downturn in hiring for AI-exposed occupations aligns perfectly with the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy timeline. In an effort to combat soaring inflation, the Fed began its most aggressive cycle of interest rate hikes in forty years in March 2022, precisely when job postings in these sectors began to fall.

The key to understanding the misattribution of this downturn to AI is that “AI exposure” and “interest rate sensitivity” are deeply correlated variables. The occupations rated as most exposed to generative AI are not randomly distributed across the economy. An analysis based on 2023 Census data reveals that occupations in the top quintile of AI exposure are overwhelmingly concentrated in sectors like “Information”, “Finance and Insurance”, and “Professional and Technical Services”.

Approximately 38 percent of workers in the most AI-exposed quintile are employed in these sectors, compared to less than 2 percent in the least-exposed quintile. These are precisely the sectors most sensitive to capital costs and broad economic uncertainty. This finding is supported by existing economic literature, such as research by Gregor Zens, Maximilian Böck, and Thomas O. Zörnerens (2020), which found that workers in tasks that are easily automated are also disproportionately affected by conventional monetary policy shocks.

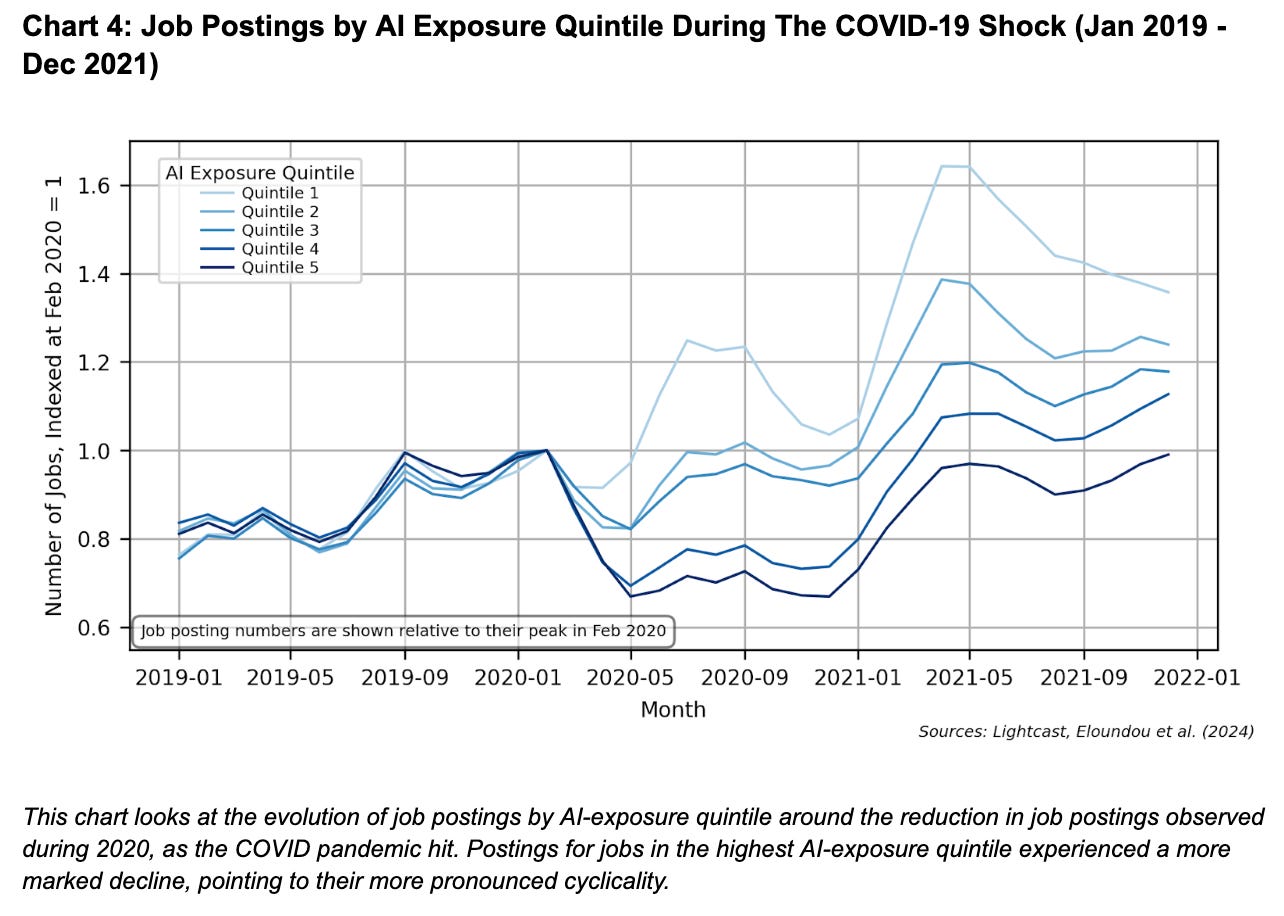

Further supporting the interpretation that AI exposure is correlated with sensitivity to macroeconomic shocks is the fact that we also see more pronounced drops in job postings for “AI-exposed” occupations during the hiring slowdown in early 2020, as illustrated in Chart 4 — when Generative AI could not even theoretically be the explanation for the difference.

Young Workers Usually Bear the Brunt of Downturns

The facts above should not be taken as minimizing the current challenges facing entry-level workers. The latest analysis by the New York Fed shows unemployment rates of 4.8 percent for recent college graduates (aged 22–27) and 7.4 percent for all young workers in the same age group — both considerably above the 4.0 percent unemployment rate across all workers. Compounding this is a notable cooling in hiring sentiment; according to LinkedIn July 2025 data, entry-level hiring rates have declined 23 percent compared to pre-pandemic levels, a steeper drop than the 18 percent decline for overall hiring.

However, the vulnerability of young workers during economic slowdowns is not a novel pattern or unique to periods of technological disruption. John Haltiwanger, Henry Hyatt, and Erika McEntarfer (2018) demonstrate, for example, that the functioning of the job ladder is highly procyclical, and more so for younger workers.

During economic expansions, labor markets are tight, and firms actively poach workers from competitors, creating abundant opportunities for advancement. During downturns and periods of economic uncertainty, this process freezes or even reverses. Hiring stops, and risk-averse workers become less likely to voluntarily quit their jobs. The result is that the primary entry points to the labor market and the key pathways for career progression disappear, leaving young workers stranded at the bottom of the ladder or unable to get on it at all. The sharp decline in job postings that began in 2022 represents a partial collapse of the job ladder. The disproportionate negative employment impact on workers aged 22–25 found by Brynjolfsson and his co-authors in the “Canaries” paper is precisely what this theory predicts.

Reassurance in the Present Should Not Preclude Vigilance in the Future

The reassuring interpretation we have provided when it comes to AI’s impact on labor market developments to date joins a large body of other studies reaching similar conclusions.

For instance, a recent analysis of the US labor market by Martha Gimbel, Molly Kinder, Joshua Kendall, and Maddie Lee (2025) finds no discernible disruption or break in aggregate employment trends since the release of ChatGPT.

Looking beyond our shores, Anders Humlum & Emilie Vestergaard (2025) leverage an extremely detailed dataset for Denmark, finding that the impact of AI on earnings and hours worked for individuals are precise zeros, with workplaces adopting AI showing no shifts in job creation or destruction. And while they evidence a decline in employment for early-career workers (as in the “Canaries” paper), the difference-in-differences analysis the authors conduct shows that AI is not the driver of this development.

All this being said, absence of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence; going forward, it is of course possible that advanced AI tools could materially alter the tasks performed by entry-level workers, potentially reducing the demand for certain foundational skills and shifting the landscape of initial career pathways.

In aggregate these changes could have a negative, neutral, or positive impact on the aggregate employment of junior workers (with David Deming’s recent convocation speech at Harvard College making the case for optimism). There could also be early-career winners and losers across different sectors, educational backgrounds or skill levels.

As David Autor and Neil Thompson (2025) explain, the impact of AI on an occupation will greatly depend on the specific tasks which are automated and what that will do to the average level of expertise for the occupation. Occupations where the average level of expertise increases could see higher wages and lower employment, whereas occupations where it decreases could see the opposite pattern.

Moreover, as David Autor and James Manyika (2025) emphasize, the degree to which technology is deployed to automate or augment human labor in an occupation is ultimately a matter of choice — with many different futures being possible at this stage. Regardless of where this all settles, it will be necessary to profoundly rethink education for the new world of work as well as on-the-job training (especially should AI take over tasks which were previously seen as formative). The set of policy questions that will need tackling is vast — and the spotlight on early-career workers from the “Canaries” paper is absolutely salutary.

Going forward, the sensible approach should be one of attentive vigilance. There is much that needs to be tracked, but we think the following should be part of any monitoring strategy:

Monitoring both quantities and prices: to their credit, the authors of the “Canaries” paper examine both quantities (employment numbers) and prices (wages); on the latter, they find little difference in compensation trends by age or AI exposure quintile. One would in principle expect wages to also be impacted in a scenario where AI is having an effect. While wage impacts can be obscured in a variety of circumstances, the variable is clearly just as worth tracking as employment levels.

Monitoring both job postings and employment numbers: part of the contribution of our article is the focus on both job postings and employment numbers, whereas the dataset considered in the “Canaries” paper solely examines the latter. It is in the job postings data that we found the clear indication that a macroeconomic effect was probably the main driver of the labor market developments under the microscope here.

Using multiple measures of AI exposure and AI usage: this is particularly important since these do not always line up — see Gimbel and co-authors (2025) — and in any event capture different dimensions.

Researching conceptual and empirical mechanisms that link AI exposure and labor market outcomes: even if we measured AI use or “exposure” perfectly, for the moment interpreting these measures rests on a lot of assumptions. Autor and Thompson (2025) show that an occupation being made more productive by an emerging technology need not automatically suffer job losses. It is important to understand better under what conditions AI exposure could present risks to better anticipate adverse outcomes and focus our monitoring efforts.

Monitoring for “new work” and task composition change within occupations and seniority levels: our concerns about the impact of AI on early-career workers are grounded in what tasks these workers have historically performed and the similarities between those and areas of high AI model capabilities. But what entry-level workers — or “AI-exposed” workers in general — do is by no means set in stone. Data on whether and how the tasks performed within occupations and within different seniority levels are evolving, for instance towards activities where human workers have a comparative advantage, is a critical missing piece of the labor market puzzle.

Coming back to the present, the difficulties of early-career workers joining the labor force are clearly an important policy question deserving urgent attention and mitigation. We suggest that viewing these challenges through the narrow aperture of AI impacts alone could cause us to miss important contributing factors and likely lead to overly narrow and inappropriate remedies. And while timing and luck may inevitably play a role in early labor market experiences, we should strive to ensure that young people have access to the ladders of upward mobility provided by employment as consistently as possible.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Guillaume Aimard for excellent research assistance. The piece was greatly improved by comments from and exchanges with: David Autor, Diane Coyle, Mohamed El-Erian, James Manyika, Ruth Porat, Michael Pisa, Michael Spence, Scott Strand, Kent Walker and David Weller. All remaining errors are our own.

Annex: Data Sources

The primary data source for this study is the Lightcast Job Posting Analytics, a comprehensive longitudinal dataset of online job postings covering over 160 countries. Lightcast is widely utilized for labor market analysis by international organizations such as the OECD and the World Bank, and is a common data source in economic research.4

To construct this dataset, Lightcast employs a proprietary machine-learning pipeline that scrapes over 220,000 unique online sources daily. The raw entries undergo a cleansing and deduplication process to ensure data integrity. Furthermore, the dataset is enriched through the extraction of other dimensions such as required skills, educational attainment, and years of experience. Lightcast standardizes these entries by mapping postings to established taxonomies, such as the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) and the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

Our analysis utilizes more than 238 million US job postings (averaging ~3.3 million monthly) from September 2019 to August 2025. The dataset is structured as a monthly time series, capturing the volume of new vacancies across 767 6-digit SOC occupational categories and 21 2-digit NAICS industry sectors. The disaggregation of job vacancies by experience buckets in this essay is also based on a proprietary classification (‘Junior’, ‘Intermediate’, and ‘Senior’) supplied in the Lightcast data, which infers the required level of experience from vacancy job titles and role descriptions.

We calculate AI exposure quintiles using the data and code provided in the replication package for Eloundou et al. (2024), using GPT-4 β scores and an equal weight scheme. We understand this is the same basis for exposure calculations as was used in Brynjolfsson et al. (2025). Finally, we use the midpoint of the upper and lower limits of the Federal Funds Target Range as the Federal Funds Rate.

UPDATE: The initial version of this post referenced and linked to an earlier version of the “Canaries” paper. That link has been replaced by a link to the most recent version of the paper. The earlier version of the “Canaries” had found a a 13 percent relative decline in employment for early-career workers (ages 22–25) in the most AI-exposed occupations since the widespread release of generative AI in November 2022. The most recent version shows a 16 percent relative decline. That update has been made as well.

Our comments in this note were written about the original version of the “Canaries” paper published on 26 August 2025. We are sharing those due to the impact of AI on young workers being a matter of critical public interest and our view that many of the key intellectual questions here are still to be settled conclusively. We understand that Brynjolfsson and co-authors are helpfully continuing to update their analysis based on feedback they received, including from us, and we link to the latest version of their paper available.

The largest business category in the U.S. Census Bureau’s Business Trends and Outlook Survey covers companies with 250+ employees. Current business adoption at the time of the survey was even weaker than planned adoption: in the same time period, fewer than 6 of businesses with 250 employees or more reported using AI technologies in the past two weeks for the production of goods and services.

This definition of exposure comes from a study by Tyna Eloundou, Sam Manning, Pamela Mishkin, and Daniel Rockloundou (2024).

See for instance: Acemoglu et al. (2022). NB: Lightcast was formerly known as Burning Glass.

I would like to point out two further research studies which look at different countries and also use different methodology, complementing Stanford's paper quite well: https://www.rivista.ai/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ssrn-5425555.pdf and https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5516798 The latter paper I helped to work with looks at UK data and we use a triple difference estimator which shows that if you are holding the firm constant, even then, more exposed shops have seen lower hiring. I think I know that interest rates affect firms, not individuals, so we can discard the interest rate evidence, at least for the UK. I think HUMLUM et al. also only covers data until 2024. I also summarized the state of evidence regarding AI's impact on young workers in my newsletter. Maybe this might be of interest to you: https://windfalltrust.substack.com/p/brief-4-ais-2025-labor-market-impacts

"Autor and Thompson (2025) show that an occupation being made more productive by an emerging technology need not automatically suffer job losses." This is an important point. Much of the current discussion about AI's impact on employment reminds me of similar discussions about personal computers back in the late 1970s and early 1980s. While some types of jobs declined, others were simply transformed, as work was conducted using new tools and methods.