The following piece features key findings from a new working paper on the effects of Opportunity Zones on U.S. housing supply, which you can find here.

Since being enacted in 2017, Opportunity Zones (OZs) have achieved a greater scale and geographic reach than any other community development initiative. By the end of 2022, the most recent year for which data is available, the OZ incentive had spurred roughly $89 billion in private investment across more than 5,600 designated communities.

But what impact is all that investment having on local communities?

Our new EIG working paper sheds light on exactly that question. It offers the first quantitative look at the causal effects of OZ investment on one of the most important indicators of local revitalization: housing supply.

And what we find is that the OZ incentive, despite its relatively low profile in recent years, has quietly become one of the most powerful tools for boosting U.S. housing supply ever to appear in the federal toolkit.

A quick refresher on Opportunity Zones

Opportunity Zones were a new incentive enacted as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and designed to attract private investment into designated low-income areas nationwide. The OZ incentive provides investors with capital gains tax benefits in exchange for qualifying long-term investments in designated census tracts.

From the moment it was passed into law, the OZ incentive has represented a true experiment in tax policy — a sharp departure from previous place-based or project-based tax incentives.

The OZ incentive:

Relies on investors using their own capital, rather than competitively awarding a fixed pool of tax credits.

Is uncapped, with no limits on how much can be invested, enabling a large scale of investment and wide reach across targeted communities.

Is “by-right,” which is another way of saying that any qualifying investment automatically receives the tax benefits.

Requires no pre- or post approval of qualifying investments from bureaucratic intermediaries, enabling greater speed and lower entry costs than typical economic development incentives.

While some of these individual features appear elsewhere in the tax code, their combination makes OZs unique. Perhaps more than anything, the policy stands out for its heavy reliance on private capital’s ability to spot opportunities in targeted communities that might have otherwise been overlooked.

While first enacted in 2017, the OZ incentive was not implemented until two years later. Implementation began in 2018 with designating the communities within which the incentive would apply. The baseline for eligibility was the “low-income community” (LIC) definition used in another place-based incentive, the New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) program. This meant that eligibility was generally limited to tracts with poverty rates greater than 20 percent or median family incomes that do not exceed 80 percent of the local area.1 State governors were able to nominate up to 25 percent of eligible tracts to be designated as Opportunity Zones.2

The OZ designation process was completed in June of 2018. But to make the incentive useful, investors needed to know more than where it would apply; they also needed regulatory certainty regarding how it could be used before tying up their capital in high-need, high-risk areas for a decade or more. This certainty would take another year and a half to arrive, as the regulations governing OZ investments were then promulgated and finalized in three waves from October 2018 through December 2019.

OZ communities: elevated distress, lagging housing production

A total of 8,764 census tracts were designated as OZs across states, territories, and the District of Columbia, amounting to roughly 12 percent of all U.S. census tracts and collectively home to about 10 percent of the U.S. population.

As a group, OZ communities lag far behind the typical U.S. community across key indicators of economic well-being. The tracts designated as OZs had an average poverty rate of 29 percent3 and a median family income 40 percent lower than the national median.4 More than 70 percent of designated tracts qualified not just as LICs, but as “severely distressed” using the U.S. Treasury Department’s Community Development Financial Institution Fund’s classifications.

It should come as no surprise that OZ communities also chronically lagged behind the rest of the country in terms of annual housing growth.

But something interesting happens following OZ implementation: designated communities rapidly begin to catch up. By 2023, they had nosed ahead of the rest of the country, and by 2024, they had pulled comfortably ahead after more than doubling their pre-designation rate of housing growth.

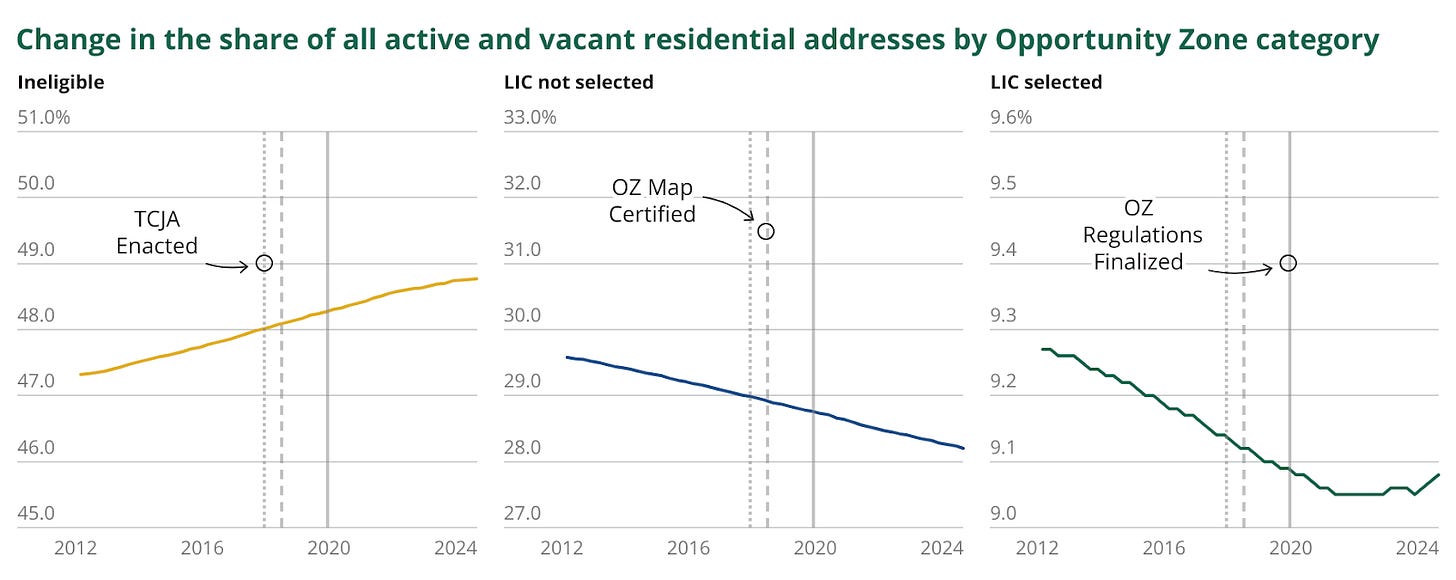

This surge in residential growth meant that, for the first time in over a decade, OZ communities were no longer shrinking relative to the rest of the country in terms of their stock of residential addresses. Importantly, this was not broadly true of all low-income communities. Low-income communities that were not designated as Opportunity Zones continued to shrink as a share of total addresses.

All of this tells us that something was going on in OZs, but it doesn’t necessarily prove causality. Just how much, if any, of the surge in housing supply within OZ communities can actually be attributed to the OZ incentive itself?

Our research is the first to answer this question.

Methodology

Making novel use of HUD data sourced from U.S. Postal Service counts of addresses, we tested the effect of the OZ incentive on the total number of residential addresses in designated census tracts. To do this, we contrasted designated and undesignated low-income communities to evaluate the effect of the OZ incentive on changes in residential addresses, both active and vacant, from Q3 2019 to Q3 2024.

This analysis allows us to produce the first-ever estimate of the new housing supply created by the OZ incentive. We then estimated the fiscal cost of the new housing supply induced by the incentive — another key and previously unknown contribution. (For a full rundown of the data and methods, see our white paper.)

Key Findings

We find that the Opportunity Zones incentive caused a large — and still rising — increase in housing supply in designated communities. OZ designation dramatically changed the trajectory of new housing in target communities, roughly doubling their number of new residential addresses over the study period. Furthermore, we find the fiscal cost per unit of housing induced by the OZ incentive to be extremely low.

Putting it all together, the OZ incentive appears to be a uniquely powerful and efficient engine of housing supply.

1. A Large and Growing Boost To Housing Supply

The OZ incentive caused an increase of 313,000 new residential addresses (not counting units currently under construction)5 in designated communities from Q3 2019 to Q3 2024 — roughly doubling the total amount of new housing added to these communities over that period.

The average effect size was 36 new residential addresses per OZ census tract. The largest effects were seen in mid-sized urban OZ tracts, with a whopping 59 new residential addresses per tract on average, but all types of communities see a significant aggregate increase.

Even though OZ communities represent only about 25 percent of all low-income communities nationwide, they accounted for over 32 percent of new housing in LICs. This overperformance is directly attributable to the OZ incentive.

Nearly one in six new residential addresses in America’s low-income communities was directly the result of the OZ incentive.

The housing effects of the OZ incentive are noticeable not only within designated communities or LICs in general, but at a national scale as well. The policy was responsible for generating 4.3 percent of the net increase in U.S. residential addresses over the period studied.

Importantly, the effect was still growing as of the final quarter of the study period (Q3 2024). This means we have yet to reach “peak OZ” housing effects, as a substantial amount of new supply is still in the construction pipeline.

2. A New Trajectory for Designated Communities

The OZ incentive has sparked a dramatic change in trajectory for designated communities. These areas have gone from laggards to leaders in new housing relative to the rest of the nation and now account for a growing share of all U.S. residential addresses.

OZ communities are now seeing their share of U.S. residential addresses grow for the first time in over a decade, which is consistent with a broader economic reconnection. Meanwhile, low-income communities that were not designated as Opportunity Zones are continuing to shrink relative to the rest of the country.

OZ communities accounted for 8.9 percent of the 7.3 million new residential addresses nationwide from Q3 2019 to Q3 2024, up from only 6.5 percent in the previous five-year period —- a 37 percent increase in share. But for the OZ incentive, designated communities would have instead accounted for merely 4.9 percent of new residential addresses nationwide.

OZ communities are now producing new housing faster than non-OZ communities. In the five years prior to our study's treatment period, the average annual growth in residential addresses in OZ communities was 0.7 percent, lagging far behind the rest of the nation. These communities have subsequently seen their average annual growth rate jump to 1.17 percent per year from 2019 to 2024. Meanwhile, non-OZ communities have seen a much smaller increase, from 1.0 percent to 1.17 percent annually. But in 2024, OZ communities jumped ahead with 1.8 percent growth, compared to 1.5 percent in non-OZ communities.

3. A Low Fiscal Cost Per Net New Housing Unit

When evaluating the effects of a housing incentive, it is important to consider not only the boost in supply it generates, but also the cost of achieving that boost. We find that OZs are highly cost efficient at delivering new housing supply.

Using the Joint Committee on Taxation’s $8.2 billion6 estimate for the revenue loss associated with the OZ incentive from 2020 to 2024, we find the fiscal cost for new housing directly attributable to OZ incentive was roughly $26,000 per residential address.7 (To be clear, that is the average amount of government subsidy required to induce a net new unit, not the total cost of building the unit.) This, however, assumes the full cost of the OZ incentive to be housing-related, which it is not. The result is that even this low estimate likely overstates the fiscal cost.

If instead we assume that 75 percent of the total cost of OZs is housing related, which reflects current analysis of the amount of OZ investment going into real estate and rental leasing, the average fiscal cost per new residential address comes down to about $20,000. This kind of cost efficiency is not the norm in the world of housing incentives.

Corroborating other research

The empirical and circumstantial evidence for a large OZ housing effect has been growing for years. Our findings comport with previous research from Harrison Wheeler that examined building permits across a sample of larger cities through 2022. That study found that OZ designation caused a “large and immediate” effect on the likelihood of development in a given tract (which jumped by more than 20 percent), as well as significant spillovers into non-OZ tracts nearby, though it did not estimate the amount or fiscal cost of new housing units created as a result.

Survey data from Novogradac of a subset of OZ investment reveals nearly 200,000 housing units built or scheduled to be built — as opposed to the completed, net new addresses in our findings — with OZ investment. (Though this survey data by its nature cannot establish causality from the OZ incentive).

Similarly, private data from RealPage found that OZ communities have more than doubled their national share of market-rate multifamily housing since the policy was enacted, though it did not establish causation or cost.

Why our findings may actually underestimate the total effect size

There are a number of reasons why our results may understate the scale or cost efficiency of OZ housing effects.

First, we exclude units under construction and completed developments that do not yet show up as USPS addresses. Because the effect is rising sharply as of the end of our study period, there is strong reason to expect that even larger cumulative effects will be observed in subsequent quarters as in-progress developments are completed for occupancy.

Second, as we are only modeling the net change in residential addresses, our totals furthermore exclude units that have been substantially rehabilitated as a result of the OZ incentive, or dilapidated housing that was demolished and replaced.

Third, as noted above, the true per-address fiscal cost is highly likely to be lower than our $26,238 estimate when considering only the share of OZ investment going into residential development.

Finally, the incentive is designed to recoup a significant amount of deferred tax revenue later in the budget window, partially offsetting the fiscal costs associated with the incentive during our treatment period. (For example, JCT currently estimates that OZs will raise over $16 billion between 2024 and 2028.)

Why these findings matter

Our findings directly address three of the main questions that policymakers should ask about any incentive policy:

Does the subsidy lead to changes in behavior or economic outcomes that would not have occurred “but for” the policy?

Did any such outcomes occur at significant scale?

Were these outcomes achieved in an efficient, cost effective manner?

The answer to all three questions is yes — demonstrating that Opportunity Zones quickly went from first-time experiment to powerhouse federal housing supply incentive, one with important lessons for other areas of tax and housing policy.

Our findings also lead us to emphasize four further points:

1. Strong evidence contradicts the most common critiques of Opportunity Zones.

OZs faced a wave of skepticism from the outset. Whether it was due to its atypically market-driven incentive structure, or the politics surrounding TCJA, or both, critiques of OZs were often tinged with reflexive antagonism to the idea that good outcomes were even possible.

The early rush to judgement by OZ critics can now be evaluated in the light of hard empirical evidence.

One early criticism of OZs was that the level of discretion provided to governors in selecting the zones would result in a map of borderline-qualifying, already gentrifying areas. When that proved not to be the case, critics seized on the flexibility given to investors in deciding where and how to allocate capital, which some claimed would inevitably result in investment failing to target genuinely distressed places. This, too, has proven wildly wrong, with years of tax data covering investments across thousands of OZ communities establishing that “OZs [are] providing a large amount of investment to distressed areas.” It turns out that low-income areas have more investment potential than either investors or OZ skeptics had previously believed possible.

Yet another vein of OZ critique comes straight from the NIMBY playbook: by spurring new residential development, OZs would drive up rents and drive out low-income residents. This one contradicts a wealth of empirical evidence demonstrating that new housing construction — including market-rate housing — lowers displacement risk and keeps rents in check. And, sure enough, the early evidence across a wide sample of OZ tracts in large cities shows that development is booming, home values are appreciating, and rents are staying put.

That brings us to the most important and persistent claim against the OZ incentive: that on the whole it merely rewards investment that would have happened anyway. If true, the policy is a failure. But instead, our findings demonstrate that the incentive caused a large-scale change in investment activity and local outcomes. But for OZs, designated communities would have only seen about half of the new housing they actually received. Thanks to the policy, OZs are now leading the rest of the country in new housing supply.

As far as “but for” stories go, that’s a remarkable change in trajectory.

It wasn’t just critics who missed the boat. Plenty of otherwise thoughtful observers and researchers did as well. One reason is that, in misunderstanding the mechanisms and timelines by which OZs spur investment and development in target communities, they a) looked for implausible effects, b) looked for effects so early after designation that none could plausibly exist, or c) both. In contrast, researchers who have looked for plausible and well-timed effects, such as ones tied to development activity, find not only statistically significant results, but ones so large that it is difficult to find an analog among other place-targeted incentives. The same is true for our results.

2. Opportunity Zones provide a new benchmark for the efficacy of place-based policy.

We noted earlier that OZs represent an experiment in tax policy. Core to that experiment is the geographic targeting of the incentive.

For decades, economists have been skeptical of place-based policies, citing their modest, inefficient, or inconsistent impacts on local outcomes. Our findings underscore that not all such policies are created equal. Indeed, the robust outcomes in OZ-designated communities not only raise the bar for what can be achieved with place-based interventions, but also suggest that legacy programs suffered from poor design rather than some inherent policy limitations.

3. Opportunity Zones are a new kind of housing policy.

Lost in the coverage of Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s confirmation hearing was this comment about Opportunity Zones: “I think that it's a fantastic way to address the housing crisis.” According to our findings, he was exactly right.

Opportunity Zones may not be the first policy people think of when it comes to housing. Nor are they only a housing policy. But the magnitude of the incentive’s effects on U.S. housing supply puts OZs firmly in the pantheon of policies that truly matter in the ongoing housing debate.

Not only that, but our findings suggest that this more flexible, market‐driven approach can indeed succeed at mobilizing private capital in ways that prior programs did not. This is hopeful news at a time when government efficiency and cost savings are in high demand.

4. Housing supply really matters.

The United States has a large and persistent housing supply shortage — one with extensive social and economic repercussions.

The need to boost housing supply has become one of the great policy challenges of our era. Thankfully, it’s also a rare area of agreement across the political spectrum, supported by a large and growing body of research that shows housing supply reduces displacement pressure and keeps rents in check.8

And here we should emphasize: all types of housing supply are important, not just “affordable” housing per se. New market-rate construction, for example, doesn’t just create housing for higher income households, but loosens the housing market for middle and low income households as well.9 This helps reduce the risk that the benefits of revitalization lead to displacement.10

On top of all this, new housing brings new people, new amenities, new demand for local business, and new tax revenue to local communities. These changes should be understood — as they are in other contexts — as an important early step in a broader cycle of local revitalization. Allowing for more time to pass for the benefits of greater housing supply to start feeding into other parts of local communities, future research should focus on measuring those eventual downstream effects: poverty reduction, employment, and other indicators of reinvigorated economic vitality.

For now, despite the bipartisan interest of policymakers and the supportive body of evidence, the effects of one of the most significant economic development policies on the books remain poorly understood. Our new research helps to fill that void.

Update: This post has been updated to include a corrected estimate for the fiscal costs per new residential address.

The statute also allowed a small share of non-LIC tracts to be designated under a “contiguous tracts” exception. Such tracts must be contiguous with a designated LIC and must have a median family income that does not exceed 125 percent of the adjacent LIC’s median family income. In total, 2.6 percent of all OZ designations were made under this exemption.

The statute included a special rule for Puerto Rico that automatically designated all qualifying tracts as Opportunity Zones.

The U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey’s 2012-2016 5-Year Estimates.

The median family income of OZs was $42,400 while the national median income was $67,900.

In the HUD data, an “active” residential address is one where a postal worker believes a person is currently living and receiving mail. Specifically, it is an address that USPS has in their database that is not classified as either short-term vacant, long-term-vacant, or no-status.

Cost estimates come from the projected cost of OZs from 2020 through 2024 in the published "Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2020-2024” prepared by the Joint Committee on Taxation.

This overstates the per unit cost of new residential addresses, because we exclude the increase in non-residential addresses (e.g., commercial addresses) caused by the incentive in designated areas. The total new address count is 340,000, which would make the fiscal cost per address $24,000.

For a review of the literature, see Been, Vicki, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine O’Regan. "Supply skepticism revisited." Housing Policy Debate (2024): 1-18.

Bratu, Cristina, Oskari Harjunen, and Tuukka Saarimaa. "JUE Insight: City-wide effects of new housing supply: Evidence from moving chains." Journal of Urban Economics 133 (2023): 103528.

Dawkins, Casey J. "Land use regulations, housing supply, and county eviction filings." Journal of Planning Education and Research 44.3 (2024): 1719-1729.