Critics of high-skilled immigration like to portray temporary student visas as a source of cheap labor, making it easy for employers to undercut the wages of American workers.1

The critics use this claim to support their preference for denying foreign graduates of American universities access to the U.S. labor market. And they might well get their way.2

Do the critics have a point?

The National Survey of College Graduates looks at workers in the United States with at least a bachelor’s degree, identifying immigrants who first arrived on a student visa, such as the F-1 or J-1. The latest update to the survey has just arrived, and what it shows clearly is that workers who first come to the country on student visas not only thrive, but typically out-earn their native-born counterparts.

The data also shows that foreign graduates are more likely to work in jobs performing R&D or to be entrepreneurs, both of which create beneficial spillovers and job opportunities for American workers.

Exactly the opposite, in other words, of what the critics allege.

While our skilled immigration system is in need of deep reforms, our imperfect status quo attracts productive workers and talent that yields benefits across the economy. Cutting off this key source of talent would be an enormous mistake.

Workers who first arrived on student visas earn high salaries.

As of 2023, there were about 2.1 million year-round, full-time workers in the United States who first came to the country on a student visa. These workers earned a median salary of $115,000, compared with $87,000 for the median native-born worker with at least a college degree — a 32 percent premium.

Student visa arrivals’ wage premium holds firm across age groups. Bucketing the college-educated workforce by age, the typical worker who arrives on a student visa earns more than the typical native-born worker in every age group, with the biggest gap among early-career workers.

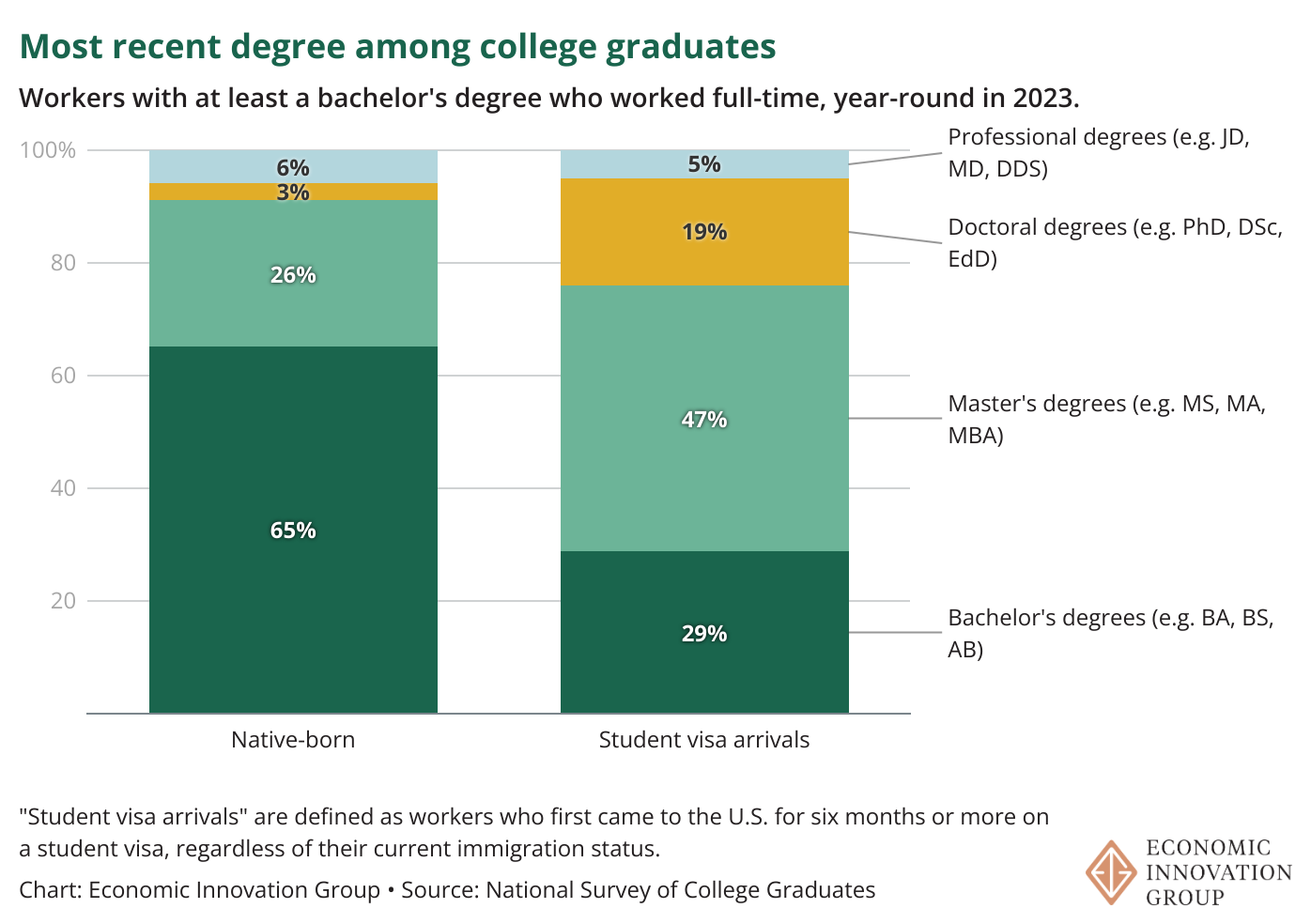

Across education levels, the earnings of student visa arrivals still compare favorably to those of natives. The typical student visa arrival with only a bachelor’s degree earned $80,000 in 2023, the same as full-time, native-born workers with only a bachelor’s degree. Student visa arrivals earn less than native-born graduates with professional degrees (e.g., JD or MD), but out-earn natives with master’s degrees or doctorates.

Professional degrees make up only a small fraction of degrees for both natives and student visa arrivals. Workers who first came to the United States on a student visa are nearly twice as likely to have a master’s degree as native students and are more than six times as likely to have a PhD.

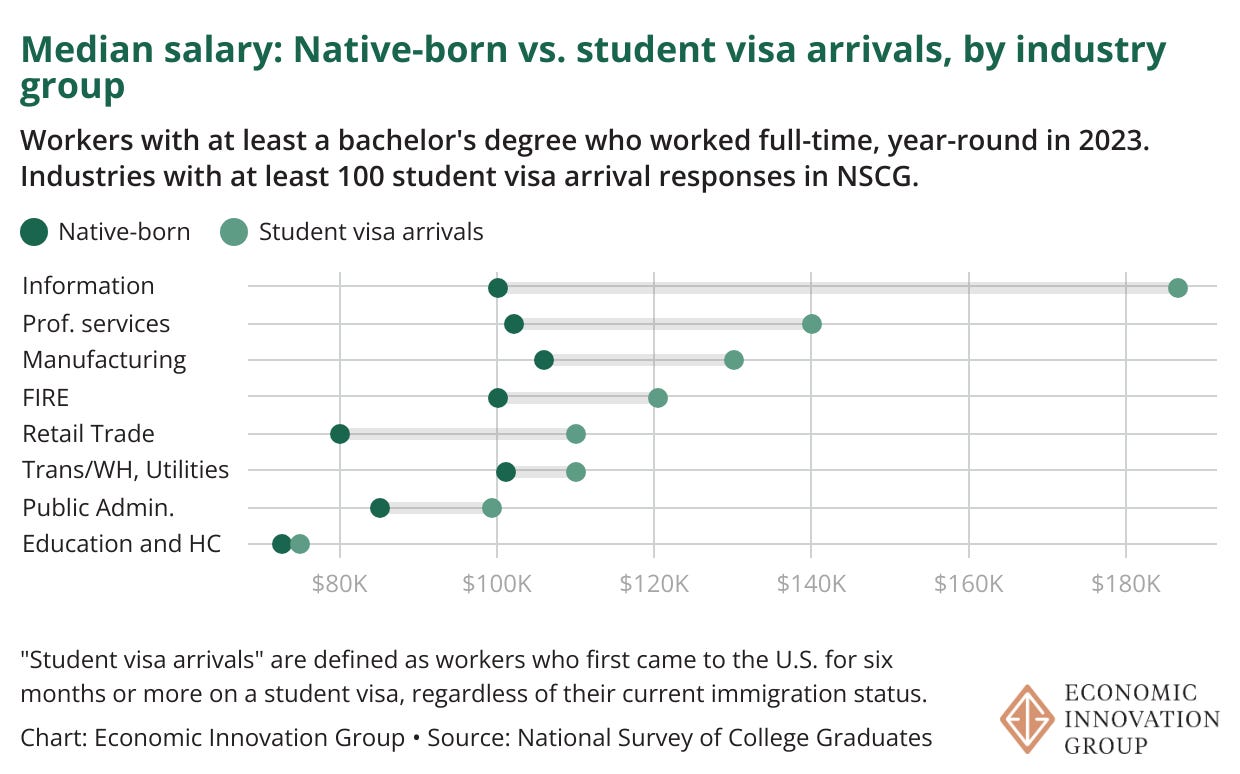

The wage premium received by workers who arrived on student visas, compared to their native-born counterparts, holds across the industry groups with the most student visa arrivals. In the information sector, the typical student visa arrival earns $86,000 more in salary income than the typical native-born worker in the sector.

Student visa arrivals from the two largest sending countries — India and China — earn particularly high salaries. The typical student visa arrival from India working full-time and year-round earned $146,000 in salary income in 2023, more than two-thirds higher than the typical native-born college graduate. Chinese graduates, too, earn well above both the typical native-born graduate and the typical student visa arrival. The administration’s plans to “aggressively revoke” the visas of Chinese students (and their ability to work after graduation) may undermine this source of talent that is evidently in high demand from American companies.

Student visa arrivals are much more likely to do R&D work.

As if the impressive earnings of international graduates in the labor market weren’t enough, student visa arrivals are much more likely than native-born students to be engaging in basic or applied R&D. In fact, they perform R&D at more than twice the rate of their native-born counterparts. Further impeding international students’ ability to stay and work after graduation would be a major blow to the United States’ R&D ecosystem.

Student visa arrivals are more likely to become entrepreneurs after obtaining permanent residency and citizenship.

Student arrivals have higher rates of entrerpreneurship than native-born college graduates. In 2023, 11.3 percent of student visa arrivals were self-employed, compared with 10.3 percent of native-born college graduates.

It is worth noting that about one-fourth of all workers who first arrived in the United States on student visas remain on temporary visas, which heavily restrict entrepreneurship. The H-1B, for example, is only usable for founders in extremely limited circumstances. Entrepreneurship rates for student visa arrivals rise after obtaining permanent status. Nearly 15 percent of student visa arrivals who have become naturalized citizens were self-employed in 2023. Making temporary visas friendlier to entrepreneurs, perhaps by rolling out a startup visa, would further boost skilled immigrants’ rate of entrepreneurship.

The growth of Optional Practical Training (OPT) is a symptom of our skilled immigration system’s dysfunction, not a cause.

Critics of student visas aren’t entirely wrong: the system today does have flaws. OPT, which allows F-1 student visa holders to work after completing their degree, requires recent graduates to work in jobs directly tied to their field of study, an arbitrary restriction that indeed creates unfair competition with native workers. If international students are allowed to work post-graduation, they should be on an equal footing with native students and allowed to work in any occupation or industry.

And as we have written extensively, degrees are not the right criteria that the U.S. should use to select immigrants. Proposals to “staple green cards to diplomas” would be a missed opportunity, likely sparking growth in degree programs of questionable economic value.

But the dramatic expansion of the OPT program over the last decade is largely not a function of abuse by either schools or students. Rather, it is a product of our inability to expand other work visas to keep up with demand or economic growth. The H-1B visa, for example, is now akin to “recruitment roulette,” where workers face low odds of winning a visa regardless of their skills or how much an employer is willing to pay them.

Absent long-overdue reforms to the rest of the high-skilled immigration system to expand high-skilled visa pathways and prioritize applicants according to earnings, OPT remains a critical bridge for American firms to sort through recent graduates and identify the talent worth investing in long-term. Ending international graduates’ ability to work would not remove low-wage competition for native-born workers and graduates. Instead, such a move would deprive the U.S. economy of highly paid workers whose skills are in high demand.

The Github repository for this analysis is available here.

Restrictionist groups like the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) and left-wing groups like the Economic Policy Institute have long questioned the value of temporary work visas and Optional Practical Training (OPT) on the grounds that such workers have low wages and compete unfairly with natives. A recent bill introduced in the House would abolish the OPT program, which allows international students to work in the country after graduation.

President Trump’s nominee to head the United States Customs and Immigration Services, Joseph Edlow, has threatened to end Optional Practical Training (OPT), which allows international students to work in the country after graduation.