There’s a better way to allocate H-1B visas

Fixing the flaws in the DHS proposal

Imagine a high-skilled immigration proposal that would prioritize an event planner earning a $66,000 salary over an electrical engineer with a $115,000 offer to work at Intel’s cutting-edge semiconductor fab in Arizona. As much as we love the event planners in our lives, this should strike most of us as a profound misuse of the limited number of high-skilled visas the United States can give away each year.

Yet a new Department of Homeland Security (DHS) proposed rule to reallocate H-1B visas would do exactly that.

The agency’s new rule would replace the random lottery that currently assigns new H-1Bs with a weighted lottery system that gives some applicants additional entries (and thus higher probabilities of winning). The proposal is an attempt to prioritize visa applicants with the most sought-after skills and highest pay. That’s the right goal, but as we show in a new letter to the agency, the proposal would badly fail to achieve it. Instead, it would grant an advantage to employers hiring H-1Bs for lower-paying occupations and exacerbate the long-running problem of IT outsourcing companies abusing the visa program.

The proposed rule would give eligible applicants a certain number of lottery entries based on the “Wage Level” of their job, as determined by the Department of Labor. Applicants would be given the number of entries that corresponds to their Wage Level (Level II applicants would get two entries, for example). Wage Levels attempt to label visa applicants based on how their salary offer stacks up against what other workers employed in the same occupation and geographic area earn. A visa applicant with an offer to be a data analyst in Atlanta has their salary offer compared to other data analysts in Atlanta, and a mechanical engineer in Detroit is compared against other mechanical engineers in Detroit.

The weighted lottery would therefore only prioritize certain applicants over others based on how their pay compares to others within their same occupation. It does not take into account differences in pay between occupations. As we point out in our letter, this leads to some outcomes that are obviously out of step with the intent of the rule:

An exercise physiologist in Jacksonville, Florida, earning $55,000 per year would be classified as a Wage Level IV applicant and given four entries into the weighted lottery under the proposed rule. A software developer in San Francisco earning $155,000, with a salary classified as Level I, would only get one lottery entry. The hypothetical exercise physiologist earns 15 percent less than the median year-round, full-time American worker. The hypothetical software developer earns nearly 2.5 times the median year-round, full-time worker.

In Huntsville, Alabama — a major hub of the American aerospace industry — a marriage and family therapist with a $65,000 salary offer (Level IV) will have twice the odds of winning an H-1B visa under the proposed weighted lottery as an aerospace engineer earning twice as much, $130,000 (Level II).

The United States is facing fierce competition with China in artificial intelligence, yet a brilliant computer and information research scientist in Seattle with a $210,000 salary offer (Level II) plus stock options would have half the odds in the proposed weighted lottery as an acupuncturist in the same area making $105,000.

Beyond these obvious distortions and the failure to place top talent at the front of the line for H-1B visas, we estimate that IT outsourcers like Tata, Cognizant, and HCL — notorious abusers of the program — would end up winning more visas each year under the agency’s proposal, not fewer.

In short, the agency needs to go back to the drawing board to design a new rule that would actually achieve its goals of prioritizing top talent for the limited number of H-1B visas available each year. As analysts who have written in great detail about reforms that Congress and the administration should make to the skilled immigration system — including a radical overhaul or replacement of the H-1B system — we have some suggestions.

Our proposed alternative: An expected lifetime earnings ranking

Rather than give lottery entries to applicants based on Wage Levels, we propose a ranking that prioritizes applicants who will make the largest economic and fiscal contributions to the United States over their working lives.

Here’s how an expected lifetime earnings ranking would work: Each H-1B applicant’s future earnings would be estimated all the way until age 65 using college graduate salary data from the American Community Survey. To demonstrate: if 26-year-old college graduates earn 3 percent more than 25-year-olds on average, then a 25-year-old H-1B applicant earning $100,000 would be projected to earn $103,000 at age 26. This projection continues year by year, and future salaries are discounted (adjusted downward) according to annual rates of either 3 or 7 percent to account for the fact that a dollar earned in the future is worth less than a dollar earned today.1

To allocate the 85,000 visas available to private-sector employers each year, we would rank applicants according to the net present value (NPV) of their expected lifetime earnings. We would meet the “regular” 65,000 visa cap with the applicants who have the highest expected earnings. For the additional 20,000 visas available under the “master’s cap” reserved for applicants with graduate degrees from U.S. schools, we would allocate visas to the remaining, eligible applicants with the highest expected future earnings.

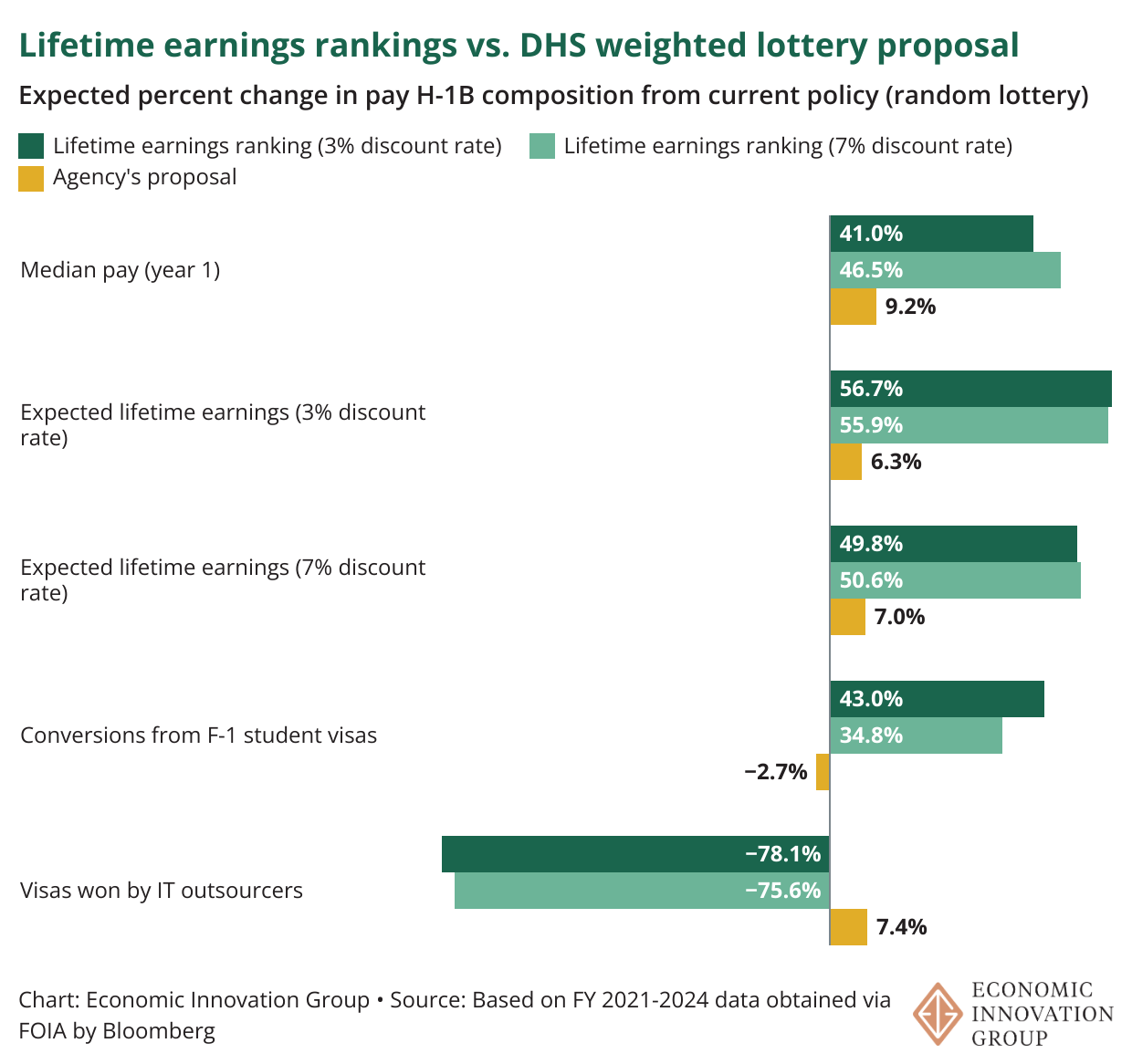

Running hundreds of simulations using data on lottery winners from FY 2021 through FY 2024,2 we find that a lifetime earnings ranking would far more effectively select for the highest-paid applicants than the proposal from DHS. The salary of the typical H-1B awardee would immediately rise to at least $140,000, which is $40,0000 higher than winners of the current, random lottery.

By comparison, the agency’s proposed rule would only modestly bump the median salary of new H-1Bs, from $100,000 under the random lottery to $109,000 under the weighted lottery. For what is purported to be the cornerstone of a plan to fix our largest skilled immigration program, these results are deeply unimpressive.

Over their working lives, the typical H-1B awardee under a lifetime earnings ranking would earn $1.8 million more than the typical winner of the random lottery and $1.6 million more than the projected winners under the agency’s proposals.3 Applied across all 85,000 awardees each year, this amounts to tens of billions of future market earnings that the current rule fails to capture. Foregone earnings also mean foregone tax revenue that could pay for public services or reduce mounting fiscal deficits.

At the same time, we estimate that the DHS proposal would actually increase IT outsourcers’ use of the H-1B program. Such companies offer relatively low pay and poor working conditions. They use visas that could otherwise go to the highest-skilled applicants meeting the critical needs of hospitals, startups, and innovative companies. An expected lifetime earnings ranking would reduce IT outsourcers’ use of the H-1B visa by between 75 and 80 percent. (For a full breakdown of the source data and methodology behind all the estimates in this post, please see the appendix of our comment letter.)

A lifetime earnings ranking would also help address one of the most serious weaknesses in our skilled immigration system: our inability to retain the engineers, scientists, and other top talent educated at our own universities. As we have found, the U.S. only retains 37 percent of international students long-term. This amounts to losing more than 100,000 students from every graduating class.

By elevating younger applicants with the greatest earning potential, a lifetime earnings-based ranking would increase the number of international students transitioning into H-1B status by an estimated 34 to 43 percent annually. The agency’s proposal, meanwhile, would lead to 2.7 percent fewer students obtaining H-1B visas. Long-term, the agency’s proposal will undercut our ability to attract and retain bright, high-earning talent, who might otherwise go work for companies in rival or adversarial countries.

Simulating alternative proposals

Using data on lottery winners from FY 2021 through FY 2024, we simulate and compare the effects of the current random lottery approach, the new DHS proposal, our preferred idea for a lifetime earnings approach (under both the 3 and 7 percent discount rates), and two other alternative options: a compensation-based ranking, and DHS’ 2021 rule that was vacated by a federal court and ultimately withdrawn.

Overall, we find that a number of different visa allocation policies outperform the most recent proposal from DHS on prioritizing higher-paid workers. In a compensation-based system that simply takes the highest-paid applicants, the median salary for new H-1Bs would rise from $100,000 to $154,000. Under this system, the bottom 10th percentile H-1B winner would earn $127,000, substantially higher than the median salary under DHS’ proposed rule.

Ranking schemes that are primarily based on salaries — such as a compensation ranking or an expected lifetime earnings ranking — are much more effective in reducing IT outsourcers’ use of the visa than proposals based on Wage Levels. The current proposed rule would boost the number of visas awarded to outsourcers by 7.4 percent. The rule proposed by the agency in 2021, which some restrictionist groups are promoting as a more promising alternative, would lead to an even larger increase of 13.8 percent. IT outsourcers tend to sponsor workers at Wage Levels II and III, but with low salaries, meaning that rules prioritizing applicants by Wage Level instead of salaries will aid their business model. DHS should choose an expected lifetime earnings or compensation ranking to both reduce these companies’ abuse of the program and significantly raise salaries in the H-1B program.

Below, we summarise the six different H-1B allocation policies.

Conclusion

There is still time for DHS to revise its proposal and align the H-1B program with its stated mission of attracting the best and brightest. Without significant changes, the new rule will empower the biggest abusers of the H-1B program while overlooking the innovators who drive long-term innovation. The administration and Congress should seize this moment to deliver a merit-based system that reflects American interests.

View the Github with code for replicating this analysis here.

Federal guidelines require agencies to evaluate the economic impact of significant rules using 3 and 7 percent discount rates.

This data was obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request by Bloomberg for a story that ran earlier this year. The data is available here. Because the universe of lottery winners is chosen at random, they are broadly representative of the applicant pool as a whole. To simulate applicant pools each year, we repeatedly sample (with replacement) this data until we reach the total number of lottery entrants that year. We then apply various allocation rules, averaging the results together across hundreds of simulated applicant pools. For a more detailed explanation of the methodology, see our comment letter.

These totals are discounted over time at 3 percent.