Where are the digital workers?

At 10 percent of GDP, the digital economy is almost certain to continue growing as a share of the overall American economy.1

That includes its workforce. From 2019 to 2023 (the last year for which the data is available), the number of workers in the digital economy grew by twelve percent, a full six percentage points faster than the growth rate for employment nationwide. Six percent of all workers are now employed in the digital economy.

Where is the digital workforce located?

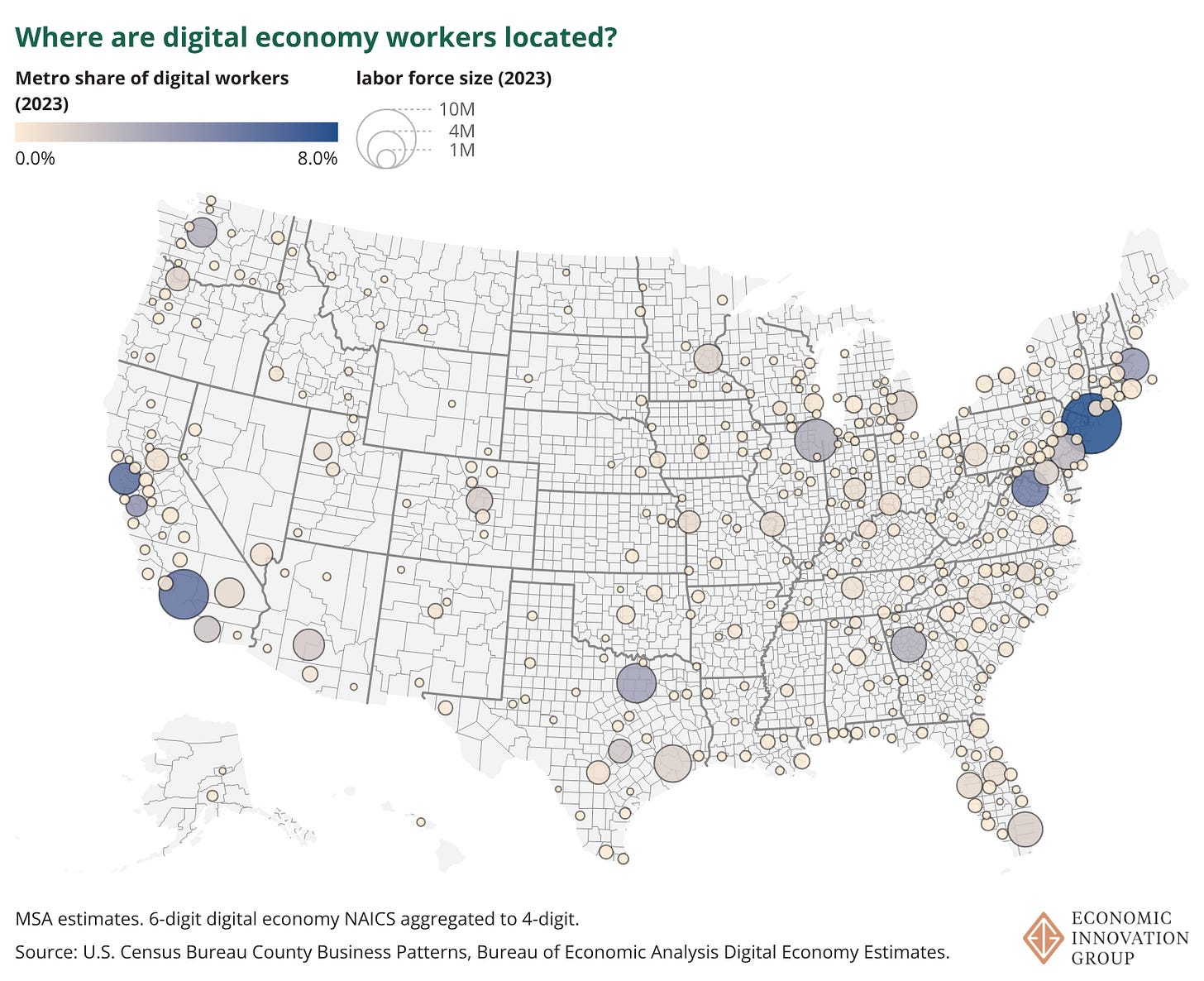

But these workers aren’t spread evenly across the country. Half of all digital workers live in just 10 metropolitan areas. The New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles metros together account for a fifth of the total digital workforce.

This should come as no surprise, as these are also among the largest labor markets in the country.

Digital Activity and Local Labor Markets

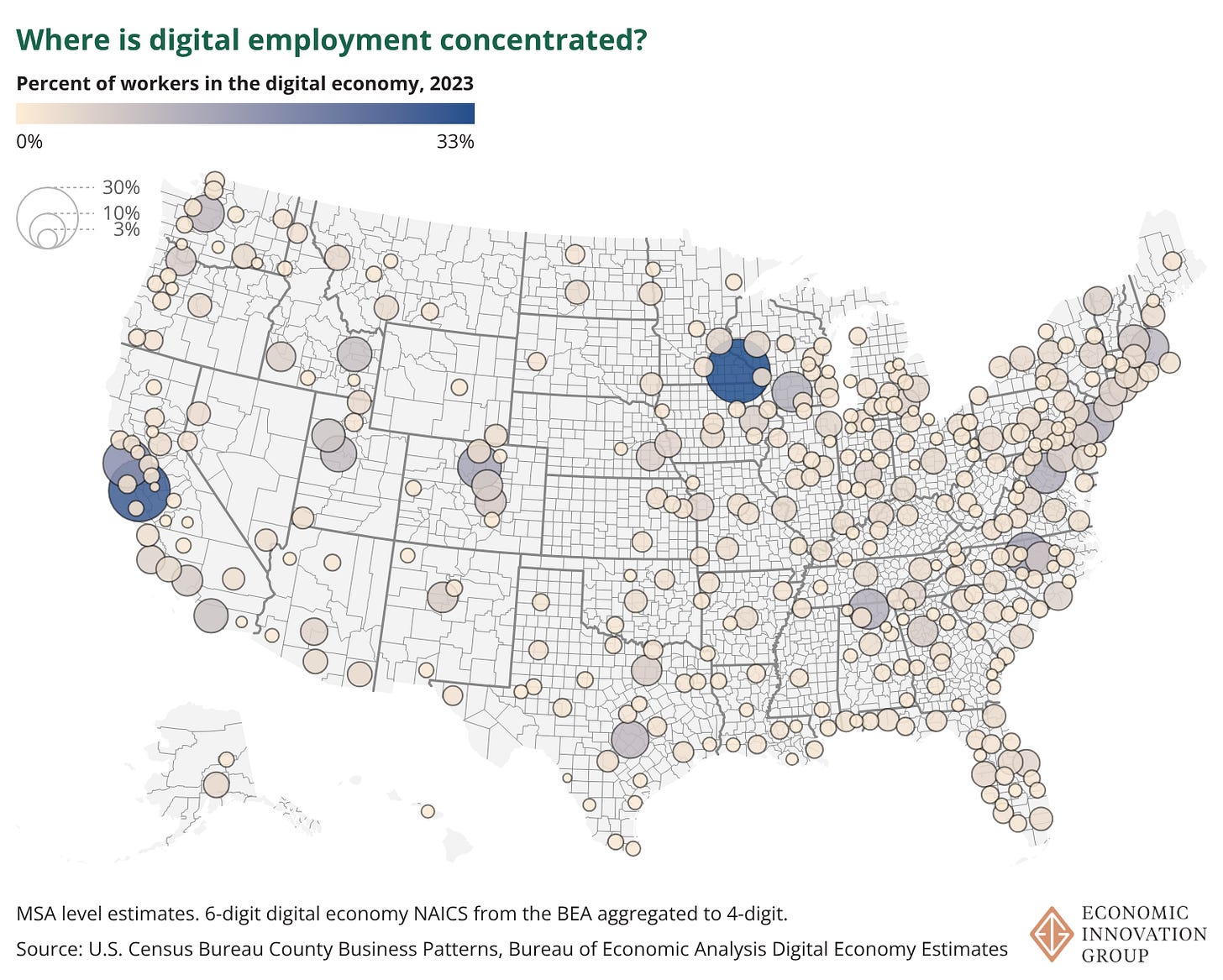

But just knowing where the most digital workers are located fails to offer a sense of where they are most important to a specific area’s local labor market.

To start with the bigger metros, 30 percent of workers in San Jose are employed in digital economy industries, while in nearby San Francisco the share is 19 percent. In the metro area of Washington, DC, with its high number of data centers, the share is 12 percent.

Other digital hubs are located in smaller metros. In Rochester, Minnesota, home to Mayo Clinic,2 a third of the labor force is employed in the digital economy – the single highest share in the nation. The university cities of Durham, North Carolina, and Madison, Wisconsin, enjoy similar shares as Washington, DC, at close to 12 percent.

New York City has a large absolute number of digital workers — unsurprising, again, given the size of its population — but they account for just 6 percent of its workforce, placing it 30th among metro areas.

Meanwhile, the share is just 2 percent in the nation’s median metro area. This contrast between the typical metro and the few places with such high concentrations of digital workers is visible in the map below.

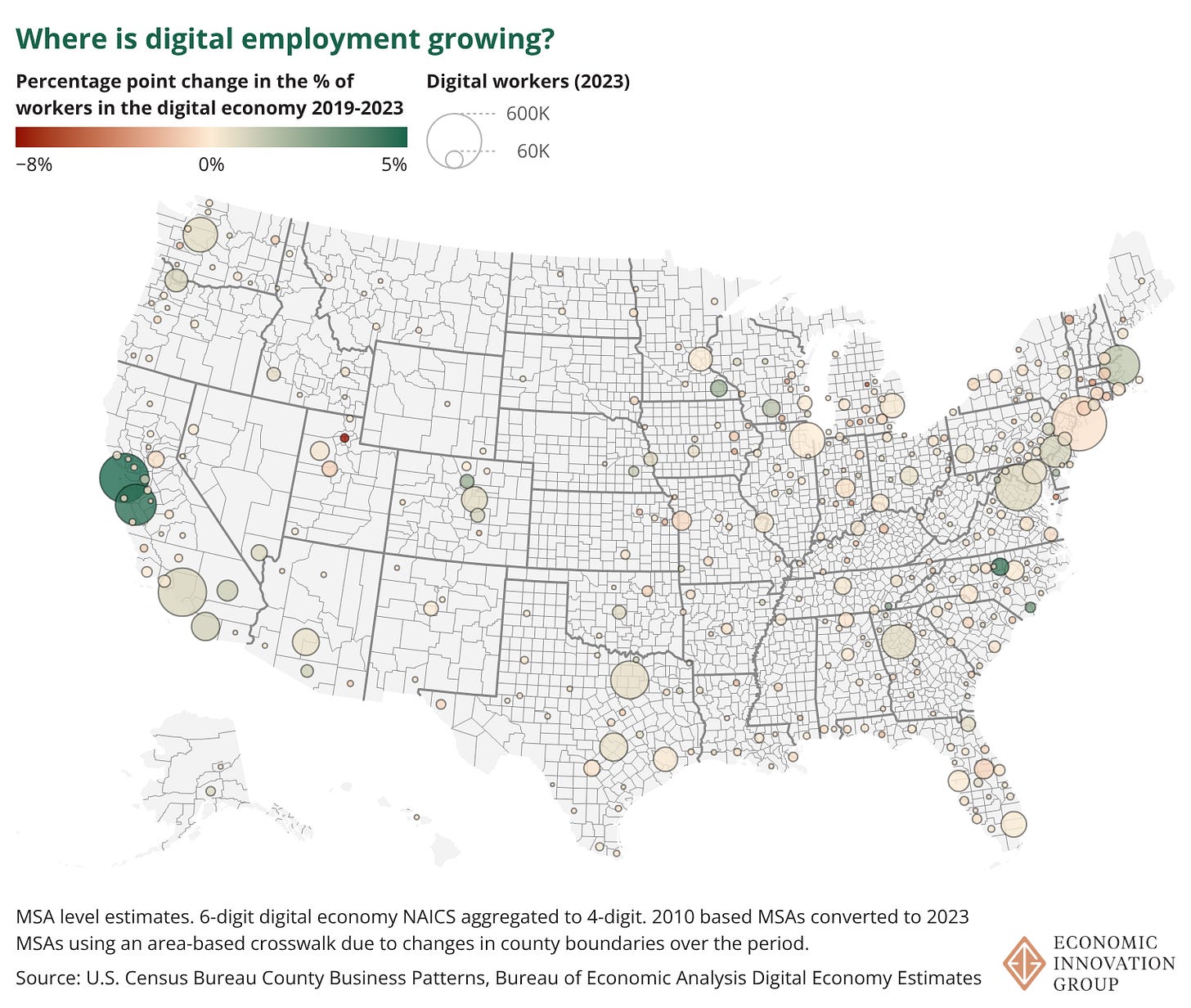

The metros with labor markets highly concentrated in the digital economy have become increasingly specialized over time. The map below shows which places have the largest percentage point changes in digital-economy workers as a share of the total labor force between 2019 and 2023. Places with an increase in specialization are green, while those with a decrease in concentration are red.

San Francisco, San Jose, and Durham experienced the largest increases in the digital share of their labor forces over the half-decade, about 5 percentage points each, while also seeing growth in overall employment.

Most of the places with the largest declines in digital concentrations are located in Michigan. It is important to keep in mind that some of these concentration declines are the result of diversifying labor markets rather than a contraction of the digital sector. Seattle and New York, for example, saw a decline in digital economic specialization, while still retaining robust labor markets in digital industries (meaning other industries simply out-hired digital businesses rather than digital businesses pulling back). In contrast, the Ogden metro area just north of Salt Lake City saw the largest drop in digital concentration, and it was the result of both increasing employment in other industries and an absolute decline of 2 percent in digital jobs.

What kinds of firms are driving the digital economy?

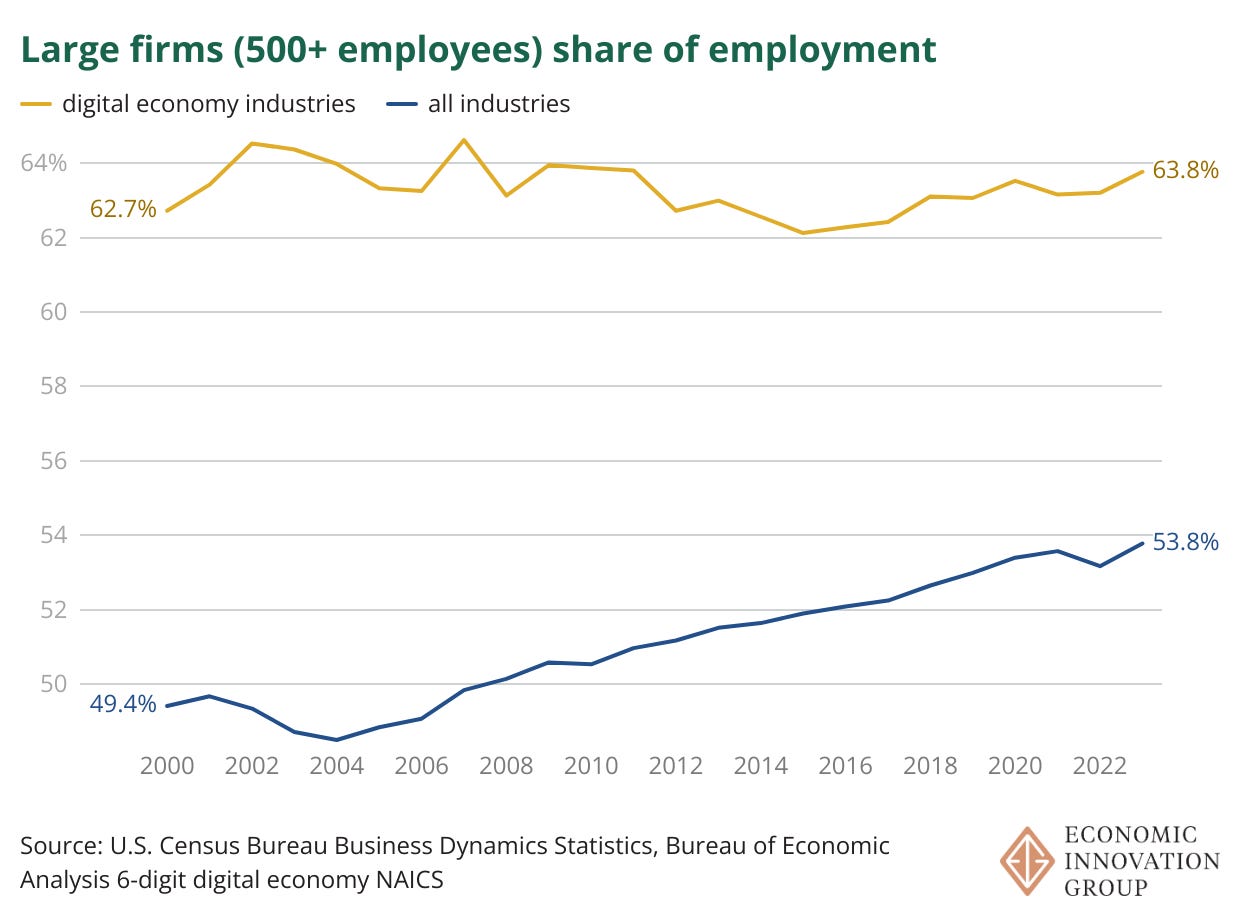

For decades, large firms have accounted for the vast majority of employment in the digital economy. Since 2000, companies with at least 500 employees have ranged between 62 to 65 percent of total employment in the digital sector. This stands in stark contrast to overall trends (in the non-digital parts of the economy). Nationally, large firms’ share of total employment has risen steadily from below 50 percent in the early 2000s to 54 percent today.

Given that the digital economy includes the Googles and Amazons, it is not surprising that large firms account for an outsized share of activity. But it is notable that within digital industries, the share of employment at large firms has neither climbed (as it has for all industries) nor fallen (as might be expected given the high rate of startups in the digital economy). Perhaps opposing pressures have cancelled each other out, but in any case the share has remained stubbornly flat through the decades.

Where is the digital economy going?

Because the most recent data is for 2023, these estimates only capture the beginning of the rise of AI. In future years, AI may enable companies to produce ever more without having to hire more workers, potentially reversing current trends. On the other hand, the enormous wave of capital investments in AI may lead to both more of a buildout (and the need for more workers) at big firms and more startup activity in the space (also requiring more workers) — leading to even more digital workers as a share of the labor force despite the enhanced productivity per worker. Both futures are plausible.

To see the data and methodology we used in this post, please go to our GitHub page.

Link to the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s Digital Economy page. The BEA defines digital services as those for which digital information and communication technologies play an important role in facilitating trade in services. This includes industries such as e-commerce, cloud computing, semiconductor manufacturing, and radio broadcasting.

Note that 2022 is the most current data available, as BEA’s series on the Digital Economy has been discontinued due to budget cuts. The BEA’s 6-digit digital economy NAICS codes are aggregated to the 4-digit level, in order to identify digital-related activity in the County Business Patterns and Business Dynamics Surveys. 4-digit NAICS codes are included only if 6-digit digital economy workers make up at least 50% of the labor force aggregated to the 4-digit level. See our github for more information.

In the 4-digit aggregation, NAICS 5417 (scientific research and development services) is classified as a digital NAICS code. Workers in scientific research and development drive Rochester’s dominance.

This write-up does a really great job of showing where digital labor concentrates, and it also quietly undermines the idea that technology naturally decentralizes work.

Curious whether you see this as a temporary concentration phase, or as something more path-dependent now that AI, data centers, and predictive systems are involved?

Thanks for this piece, Sarah. It’s really thought-provoking.