Why Place Matters More Than Ever

Key themes from EIG’s 2025 Power of Place conference

Does place matter? To loyal readers of Agglomerations, obviously. But newcomers may not be so sure, while others may not even understand the question. Some cretins might even be so bold as to say that place is incidental in life and economics.

We at the Economic Innovation Group are place people. We firmly believe that place is central to the economic and social outcomes that we care about.

We know that place is a causal vector for economic advantage. Innovation and competitiveness are rooted in place, and good jobs are found in local labor markets.

We also know that place is a causal vector for disadvantage. Neighborhoods can constrain opportunity sets, and the injustices of the past live on in place.

And we know that place matters to national economic and political discussions precisely because place matters so much to people, who want their communities to thrive.

It’s for these reasons that EIG convened its second Power of Place summit last month under the theme, “Enduring Relevance in an Uncertain World.” The day was about articulating why and probing how place matters.

Here were some of the key themes that emerged:

Lots of common ground

Across an ideologically diverse set of speakers and panelists there was no real disagreement that:

We (collectively, as a nation) need to do better by our places.

Thriving communities are a legitimate democratic expectation.

A nation cannot be strong if it does not rest on strong regions.

Place-based policy, it would seem, is a safe space. For all the comity, however, there was more agreement on the ends than the means, and policy priorities differed across the different political camps.

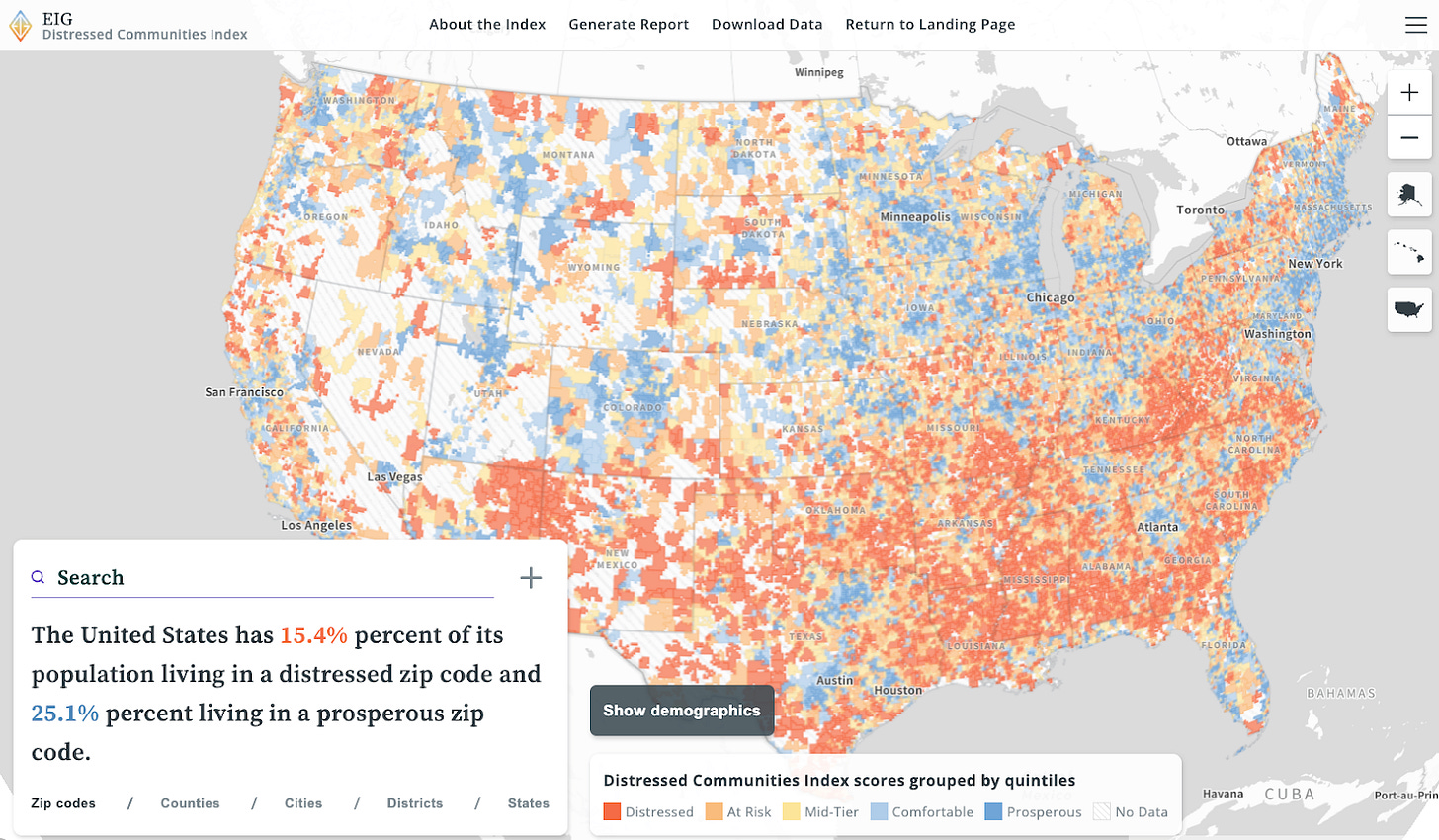

What else unites us? Maps! The Washington Post’s very own Andrew Van Dam chaired the “Maps Mania!” lighting round session in which speakers shared their evidence for why place matters. Here was the winning entry, as selected by Andrew, and whose title we especially appreciate.

At the end of this newsletter we also display all the other maps presented.

The case for place-based policy grows more precise

The day opened with a conversation about the future of place-based policy. The passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), which made a slew of community development tax incentives permanent, was only the latest in a long line of recent place-based legislative achievements.

Bipartisan place-based ideas infused every major legislative package passed during the Biden administration, and OBBBA’s signature place-based plank was extending Opportunity Zones, itself enacted during the first Trump administration.

As Rohan Sandhu of Harvard pointed out, these efforts all build on a bipartisan heritage extending back to Presidents Clinton, H.W. Bush, and the era of Great Society programs before that.

Panelists reminded us why we do place-based policy. Left-behind places are proliferating. People deserve opportunity close to home. The nation is weaker when large chunks of the population live in economically underperforming areas. And in most cases, there’s no substitute for the federal government, which has the tax base to marshall resources on an unmatched scale.

But diagnosing a problem and having an effective treatment for it are two very different things.

The keynote conversation with Jason Furman took a critical eye to the treatments on hand. To the economist, good intentions don’t matter. Identifying a problem isn’t sufficient. An effective intervention needs to be correctly designed, capably implemented, and delivering of a benefit that outweighs its cost. A high bar, indeed — and one that Furman objectively fears most place-based policies don’t clear.

Jason’s advice to make the most of the place-based policies that do pass into law:

The earlier that policy tries to intervene in an industry’s life cycle — or the less settled into an industry already is to a particular geography — the greater the ability to nudge that industry towards particular places.

He encouraged policymakers to be clear about their goals. As he put it, if your goal is to cure cancer, it’d be hard to convince him that the money should go somewhere other than Boston (or similar research centers with the established expertise). In this example, a policy aimed at curing cancer should not be bundled together with a policy aimed at boosting left-behind places. Keep them separate. Once you start to bundle too many goals, it’s hard to truly accomplish any of them.

Furman’s second recommendation was to be honest about trade-offs. Policymakers should state why they believe trading economic efficiency for geographic equity is a compelling public policy proposition. Too often, politicians fail to acknowledge that trade-offs exist — and they degrade the quality of public debate in the process.

As to the politics of place-based policy? EIG’s own John Lettieri perceives that the demand for place-based solutions is so high that policymakers face little political risk in experimenting. He’d much rather get caught trying to help communities navigate choppy seas than have to clean up a shipwreck after the fact.

The capacity conundrum

The thing about place-based policy is that its success isn’t just contingent on good design at the federal level. Success depends on places themselves and their ability, or capacity, to harness federal resources for local growth and development.

The conversation around capacity — what it means and how to build it — started laying bare partisan differences.

To me, capacity is the white whale, the residual, the dark matter of economic development. The je ne sais quoi of the local institutional environment that determines whether a place gets more, less, or basically the sum of its parts from its efforts in our messy, fragmented, and fractious governance model.

On the left, capacity is generally thought of in terms of the staffing, resources, and expertise required to win a federal grant or execute an economic development strategy or project.

On the right, capacity is usually more focused on delivery — whether a jurisdiction or community is capable of delivering a project on-time and on-budget.

You could say that the left is focused more on the quantity of capacity out there (i.e., how many places have how much of it) and the right is more focused on the question of whether it’s any good, or the quality of it.

New York City came up a lot throughout the day. Manhattan Institute president Reihan Salam appeared on stage, while the New York mayoral election was just days away.

On quantitative measures, the city is surely among the highest capacity places in the country when it comes to staff, credentials, and resources. But is New York City, with its web of actors and interests, institutionally capable of delivering a major economic development project on time and on budget (a certain tunnel comes to mind)? Our fair readers might agree to disagree.

The left wants to incubate more capacity in more places and generally prefers policy tools like grants for rural areas to professionalize their economic development operations. On the right, there’s more of a “git ‘er done” mentality, and a desire for the federal government to use more powerful carrots and sticks to encourage or compel locals to get their house in order before the federal taxpayers pony up.

The two approaches aren’t necessarily at odds, and the reality is we probably need a bit of both. But they reflect different priorities and beliefs.

Programs versus tax policy

There were also subtle but clear differences in the types of tools favored by the two political camps.

Both Democrats and Republicans share an interest in making markets work better. Republicans were readier to emphasize market-based tools as levers of place-based policy, however, and Democrats were readier to celebrate programmatic ones.

Opportunity Zones are a great example. Originally a bipartisan idea, today Republicans sing their successes (and they made OZs permanent this summer in the OBBBA), while Democrats are more ambivalent. Republicans are inherently more comfortable with a broadly available capital gains tax incentive to restore market activity in distressed areas; Democrats can’t quite scrap the impulse to turn OZs into a centrally-administered program granting awards to specific entities to do specific things. Both parties support OZs, but Republicans tend to be more excited about them and more comfortable with the nature of the tool.

In contrast, the left-leaning folks in the room were more likely to celebrate grant programs — both their design and what federal dollars could do on the ground.

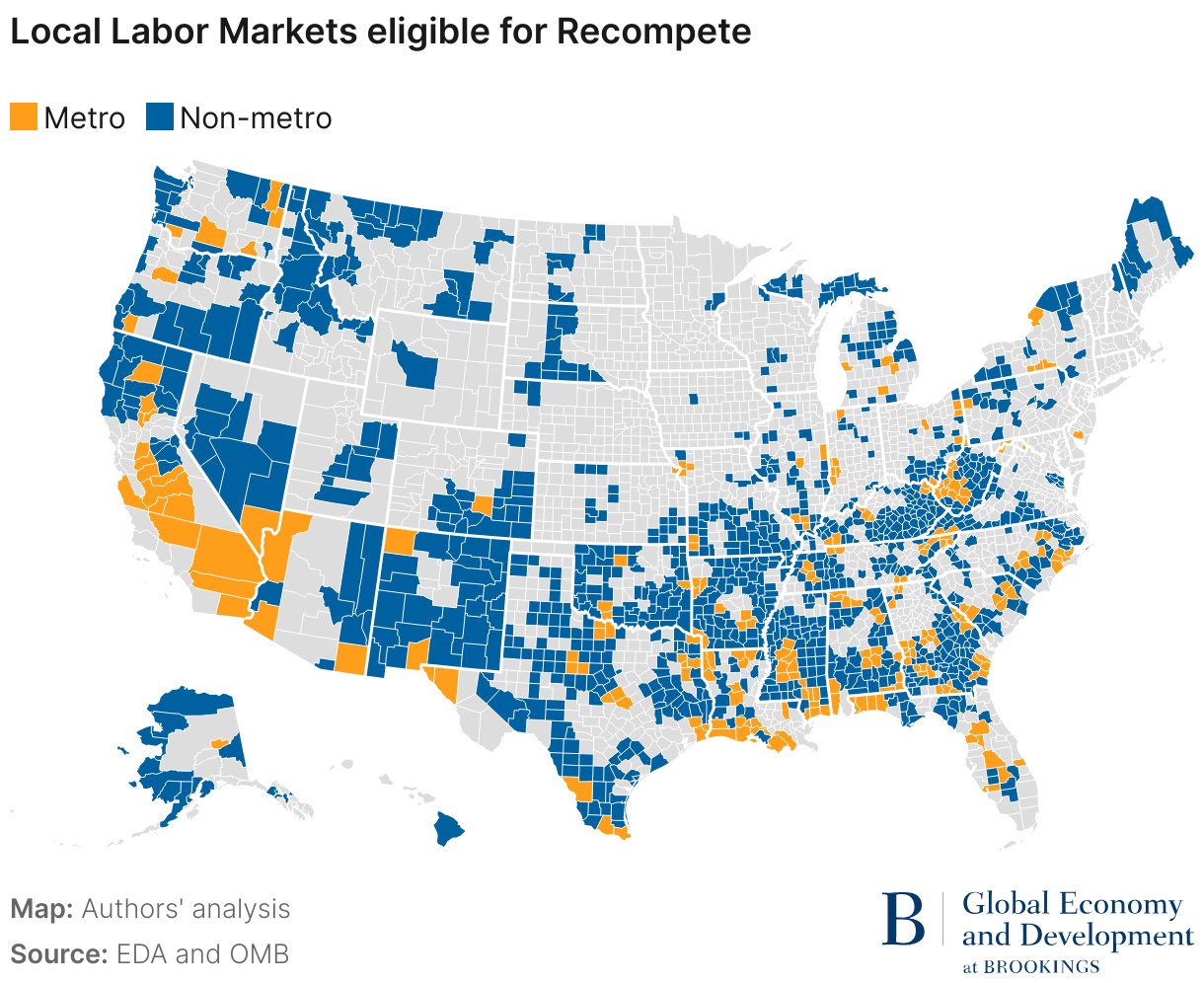

Take the Recompete Pilot Program (the legislative architect of which, Derek Kilmer, chaired the first panel).

Recompete doesn’t just try to correct for a market failure; it tries to repair the damage. Grantees take on the hard, multidimensional work of getting the long-term unemployed back into good jobs. It’s designed to test the limits of what a federal grant can achieve in a community — an idea that sets the technocratic hearts of the Democratic elite aflutter.

Recompete directly takes on some of the top public policy concerns of the Republican coalition — restoring work in rural areas like Appalachia — but the party’s public embrace of the young program has been more muted.

Provocatively, tariffs were floated by Mark DiPlacido of American Compass as a place-based policy, too. Tariffs are broad market-based tools that function as a tax. In a hypothetical best case scenario, that tax could serve to induce more production to the United States, bringing investment and jobs back at a scale that any program would struggle to achieve.

In practice, of course, tariffs serve as a tax on the imports that U.S. producers need to innovate, compete, and thrive at home and abroad. Artificially raising production costs leads to a deadweight loss that cannot be recouped. Gary Winslett of Middlebury College argued that the likelier impact of tariffs will be to erode the nation’s industrial base.

Tariffs aside, all major place-based policies of the past decade have enjoyed strong bipartisan backing. Both parties seem to accept the need for both sets of tools and support their passage. Still, Democrats like programs more, while Republicans prefer tax tools.

Back to basics

One simple, recurring theme: places need to hone their basic competitive proposition vis a vis people and firms.

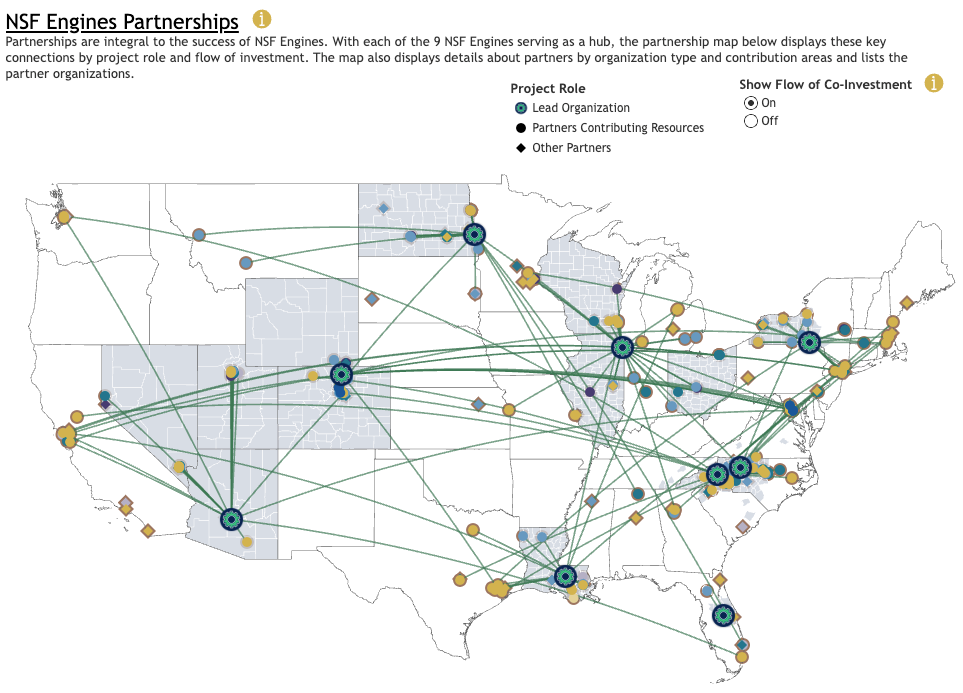

Consensus in the room was that the federal government, under the Trump administration, will pull back from major direct engagement in economic development over the next several years. OZs are now locked in, and cautious optimism is growing around programs like the Economic Development Administration’s Tech Hubs for National Science Foundation’s Engines that support the administration’s technology ambitions, but most people expect less investment in economic development on net and fewer new ideas.

The coming hiatus in federal leadership gives places the opportunity to turn the mirror back on themselves.

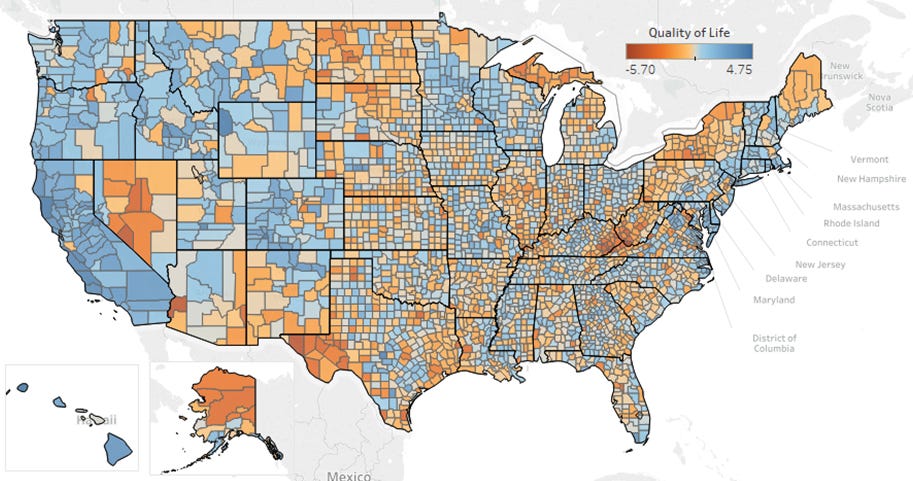

Some places are naturally blessed with a “quality of life superpower,” as Reihan Salam put it and as Ball State University’s Michael Hicks visualized for us. Graced with water, mountains, and sometimes even enlightened leadership, certain locales will always be in demand, enjoying insurance against economic twists and turns ahead.

Other places have single-mindedly cultivated their superpower and now protect it fiercely — think suburban enclaves with large lots, good schools, high HOA fees, and lawncare and landscaping worker location quotients that’ll have the Real Housewives of Carmel, Indiana, gazing out a bay window. These places offer quality people are willing to pay for.

After a good, hard look in the mirror, how many places can really be content with their value proposition?

The housing crunch makes this question urgent. As living becomes increasingly expensive, people grow more sensitive to cost differentials. Communities that cannot offer sufficient people the home they want at a price they can afford will struggle to attract and retain residents.

Commentator and podcaster Matt Yglesias sees the nationwide housing affordability crisis as a bipartisan opportunity: whether you care about the dynamism of cities or the ability of families to have and raise children (or both!), you now care about housing. And housing may be the economic issue of our time over which state and local governments have the most control.

In all their messy glory, cities have it harder than more homogenous jurisdictions, because they often combine both the best and worst that places have to offer: amenities and crime, diversity and congestion, good jobs and high taxes, beautiful buildings and indefatigable NIMBYs. Fall out of balance on any of these fronts, and places can see their competitive standing erode quickly.

Pandemic-era out-migration should have served as a massive wake-up call. This shock sent people scattering, primarily away from cities to places that offered better value. Too many places still stake their future on inertia and the assumption that people and firms are too sticky to ever leave. Too few proactively cultivate reasons to stay.

There (might) be dragons

As Ryan Smith from the U.S. Economic Development Administration noted to me afterwards, the entire day was suffused with a sense that the changes coming are bigger than anything we’ve had to deal with before.

Think about it:

For nearly a century, trade and globalization have basically moved in one direction: towards liberalization and integration. No longer.

Demography — specifically a young and growing population — once provided reliable tailwinds to economic growth. Now, large swathes of the country are in outright population decline. Managing that will be uncharted territory.

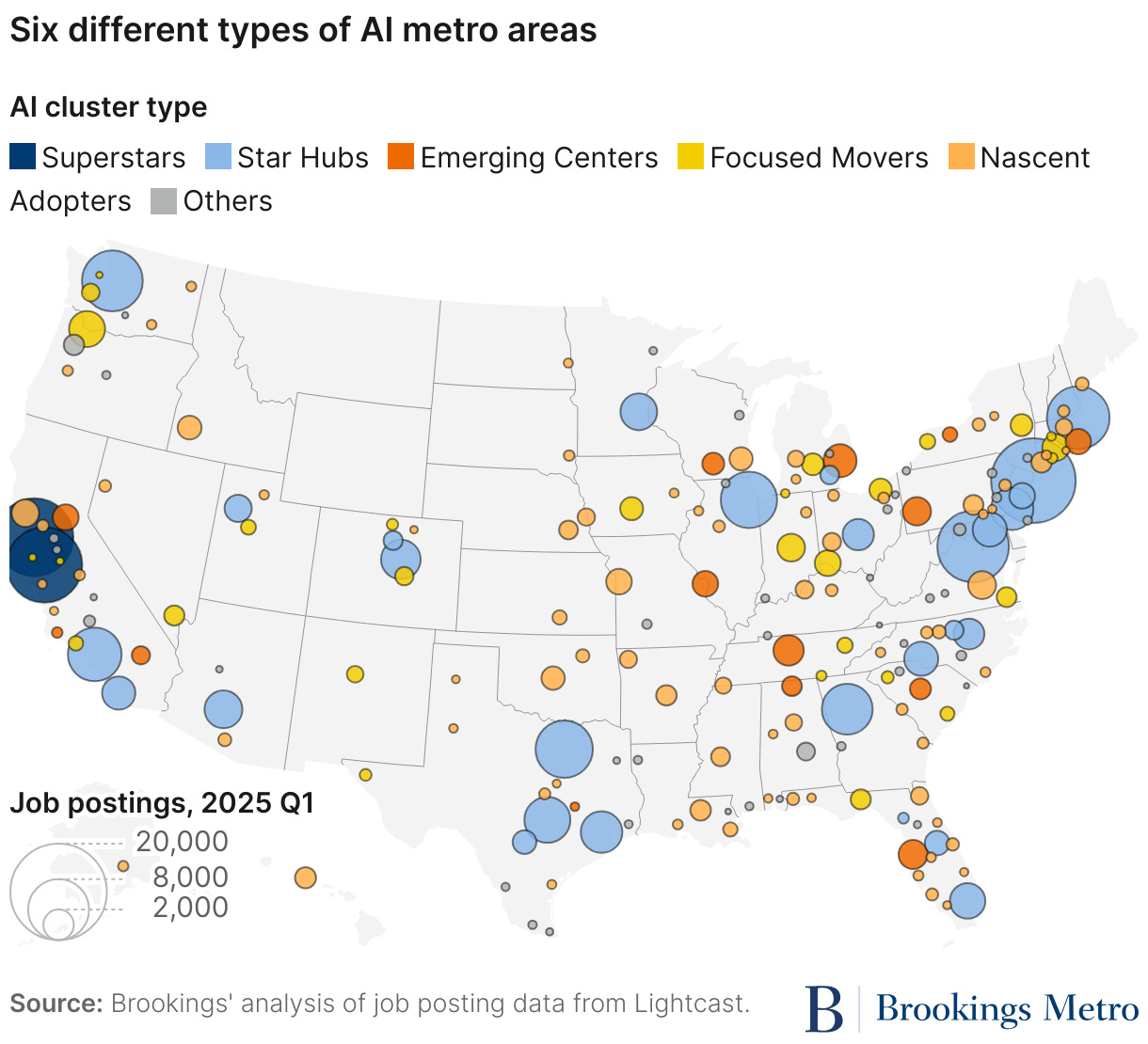

AI may prove to be the biggest technological shock to hit a mature economy with a mature demography and much lower rates of underlying dynamism than any that preceded it. For AI-pessimists, that heightens the perceived risk that the technology’s labor-saving impacts might outweigh its job-creation potential. For AI-optimists, a chance — perhaps slim, but definitely real — to bridge heretofore unbridgeable economic divides.

Has humanity gone through greater ructions than those we have swirling today? Sure. But in our lifetimes? Since economic development emerged as a field? In the career span of a typical civil servant? Probably not. What’s coming feels seismic.

The enduring relevance of place is that, come what may, places will remain. Places will mediate economic and social forces, be differentially impacted by them, and evolve in response to them. To paraphrase Yglesias, place will be constant, but places will not, cannot, and should not be static. Place will continue to shape how Americans experience the economy, and place will continue to determine where and whether they thrive.

APPENDIX — ALL THE MAPS FROM MAPS MANIA!

Presented by Michael Hicks of Ball State University

Presented by Daniel Goetzal of Harvard University

Mapping the prime age employment gap

Presented by Tony Pipa of the Brookings Institution

Presented by Mark Muro of the Brookings Institution

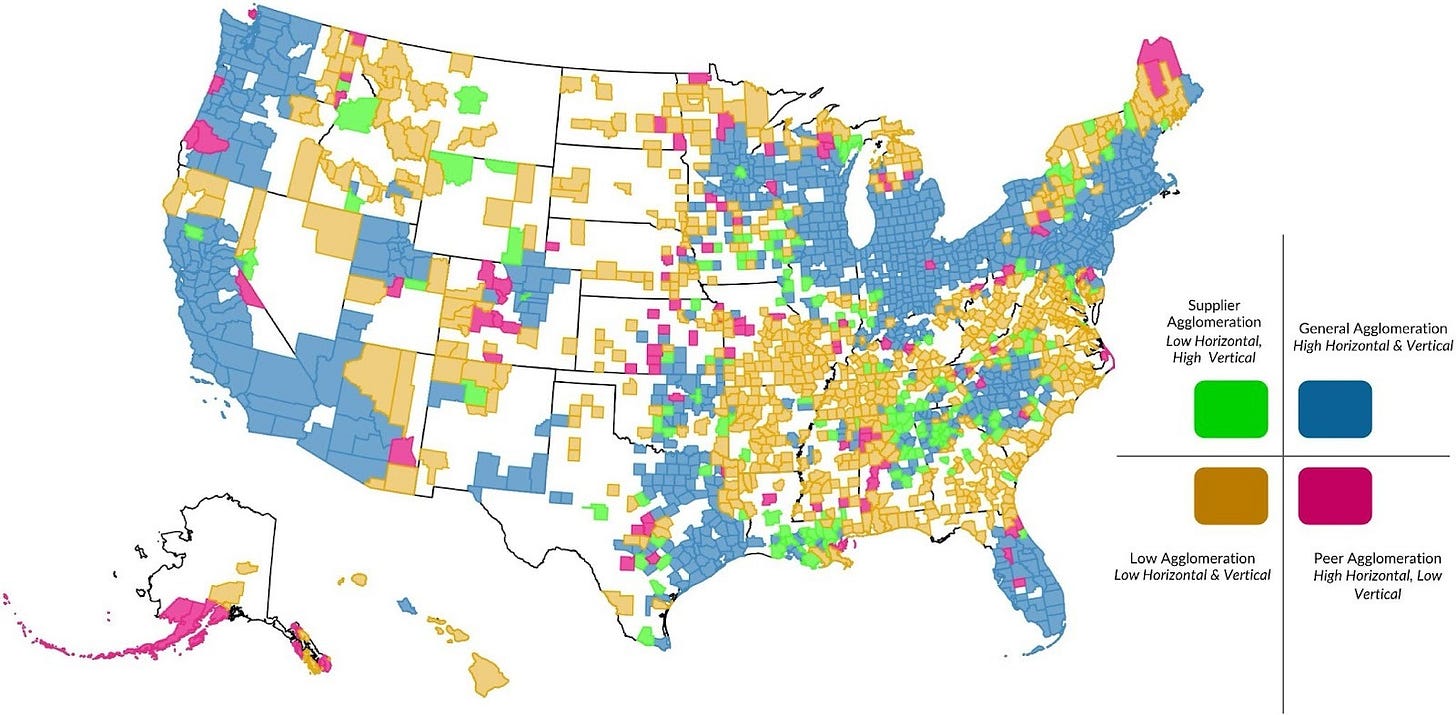

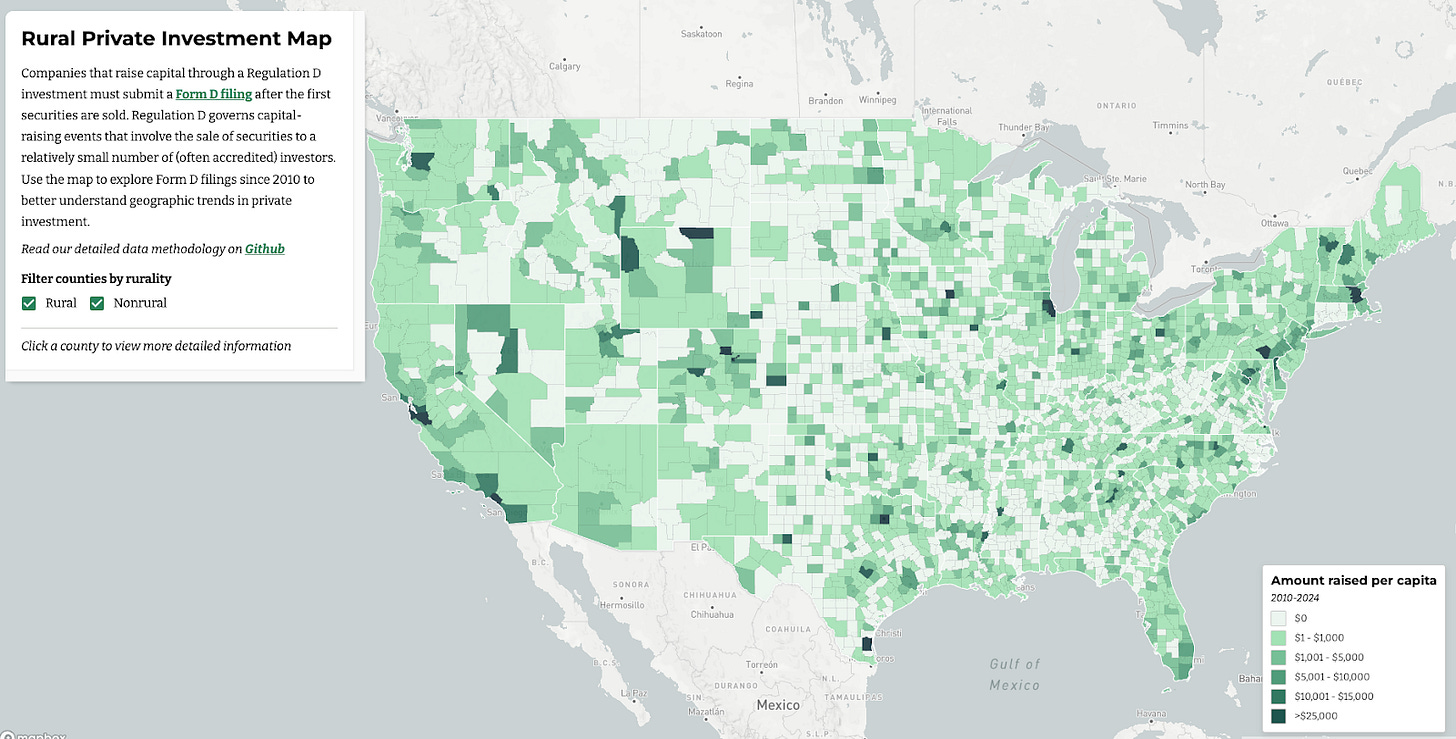

Presented by Amanda Weinstein of the Center on Rural Innovation

Presented by Kenan Fikri of the Economic Innovation Group

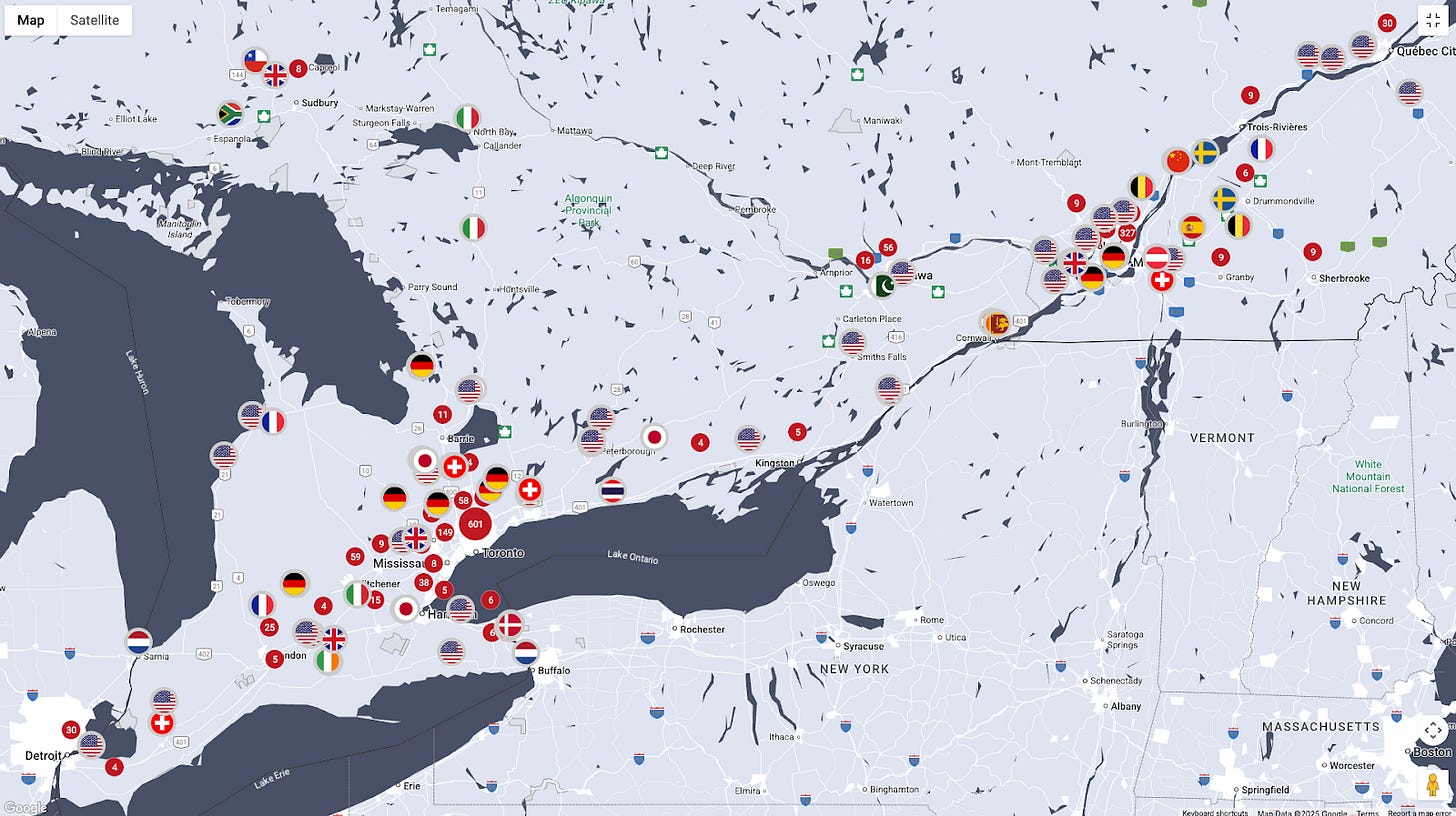

Invest in Canada Investment Map

Presented by Glenn Barklie of FT Locations

The one sure public policy that will cause owners of locations to bring the land they hold to its highest, best use is to publicly capture the full economic rent (i.e., the potential annual rental value) of the location, while exempting what building or buildings are constructed thereon. Market forces will then do the rest.