“American steelworkers, auto workers, farmers and skilled craftsmen… They watched in anguish as foreign leaders have stolen our jobs, foreign cheaters have ransacked our factories and foreign scavengers have torn apart our once beautiful American dream.” — President Donald Trump announcing his tariff strategy in a Rose Garden speech on April 2nd

White House senior counselor Peter Navarro has said that the goal of President Trump’s tariffs is “to fill up all of the half-empty factories that now are operating at low capacities around Detroit and the greater Midwest area.”

Will the tariff strategy succeed in returning good blue collar jobs to manufacturing workers in deindustrialized regions of the country?

We will know the answer in time.1 But while we wait, I can point to at least three obstacles the administration will confront.

1. The new jobs are extremely unlikely to be created in the same places as the jobs that were lost to deindustrialization.

Since the 1980s, the Northeast and northern Midwest of the country have suffered acute job losses. Non-college workers in these regions experienced an especially sharp decline in access to good jobs.2 Many of the displaced workers transitioned into lower-paying service jobs, enduring long-term earnings losses and remaining stuck in communities marked by persistently lagging economic opportunity.

In contrast with more highly educated peers, non-college workers are less geographically mobile — less able to relocate to other regions of the country in pursuit of better jobs in growing industries. And geographic mobility has further declined for workers in areas of the country that have experienced trade shocks in recent decades.

This lack of mobility matters. Unless the new manufacturing jobs return to the exact same places where they were first lost, displaced workers are unlikely to relocate to where the new factories are.

Which is bad news, because the new opportunities for work have since migrated to other parts of the country. Since the 1980s, job growth for non-college workers has been stronger in the South and Mountain West — primarily in construction, distribution, and service sectors. It has not occurred in the regions that experienced the greatest employment losses due to trade exposure.

More recently, manufacturing job growth has largely taken place far from the places that most suffered from the initial “China Shock” of the early 2000s. New factories are likely to cluster in areas where manufacturing is already resurging, the South and the West.

Tariffs have no place-based component. They can’t direct where new factories and jobs wind up — and it is unlikely they will be found in the places where they were first lost.

2. New jobs created by tariffs will be intrinsically precarious because of the tariffs themselves.

Trade barriers can be erected quickly, but they can also be dismantled just as fast.

Firms considering large capital investments need policy stability. So do the communities hoping to rebuild around new sources of employment. No one benefits from an environment of uncertainty — least of all the workers at the heart of this agenda.

A tariff agenda brings unavoidable uncertainty:

Limited long‑term investment.

If firms cannot count on sustained protection, they have little incentive to build new factories or retool existing ones for domestic production. Instead, they may choose to maintain smaller, less efficient operations — undermining the scale of potential employment gains.

Retaliation risks.

Trade partners are likely to respond in kind, imposing tariffs on American exports. Retaliation thus limits the international market of buyers and the scope of potential business. When that shrinks, so does investment — and so does the ability of factories to keep workers employed.

Higher costs.

Tariffs act as a tax on inputs, raising production costs across the economy. That translates into tighter margins for manufacturers reliant on imported components — and therefore less money to pay workers.

Job displacement in other sectors.

Tariff-induced gains in blue collar factory jobs do not exist in a vacuum. Tariffs can directly threaten blue collar jobs in non-manufacturing parts of the economy. Construction and agriculture — two of the largest sources of non-college, blue collar employment — are particularly vulnerable to rising input costs and retaliatory tariffs by other countries. A policy intended to create jobs in one part of the economy risks displacing similar jobs elsewhere.

In effect, even if tariffs generate the kind of manufacturing opportunities their proponents envision, those gains are rooted not in economic fundamentals but in political conditions. The future of jobs created by a tariff strategy is therefore as uncertain as the whims of the politicians who imposed it.

3. Manufacturing jobs are no longer as well matched to blue collar workers as they were in earlier decades.

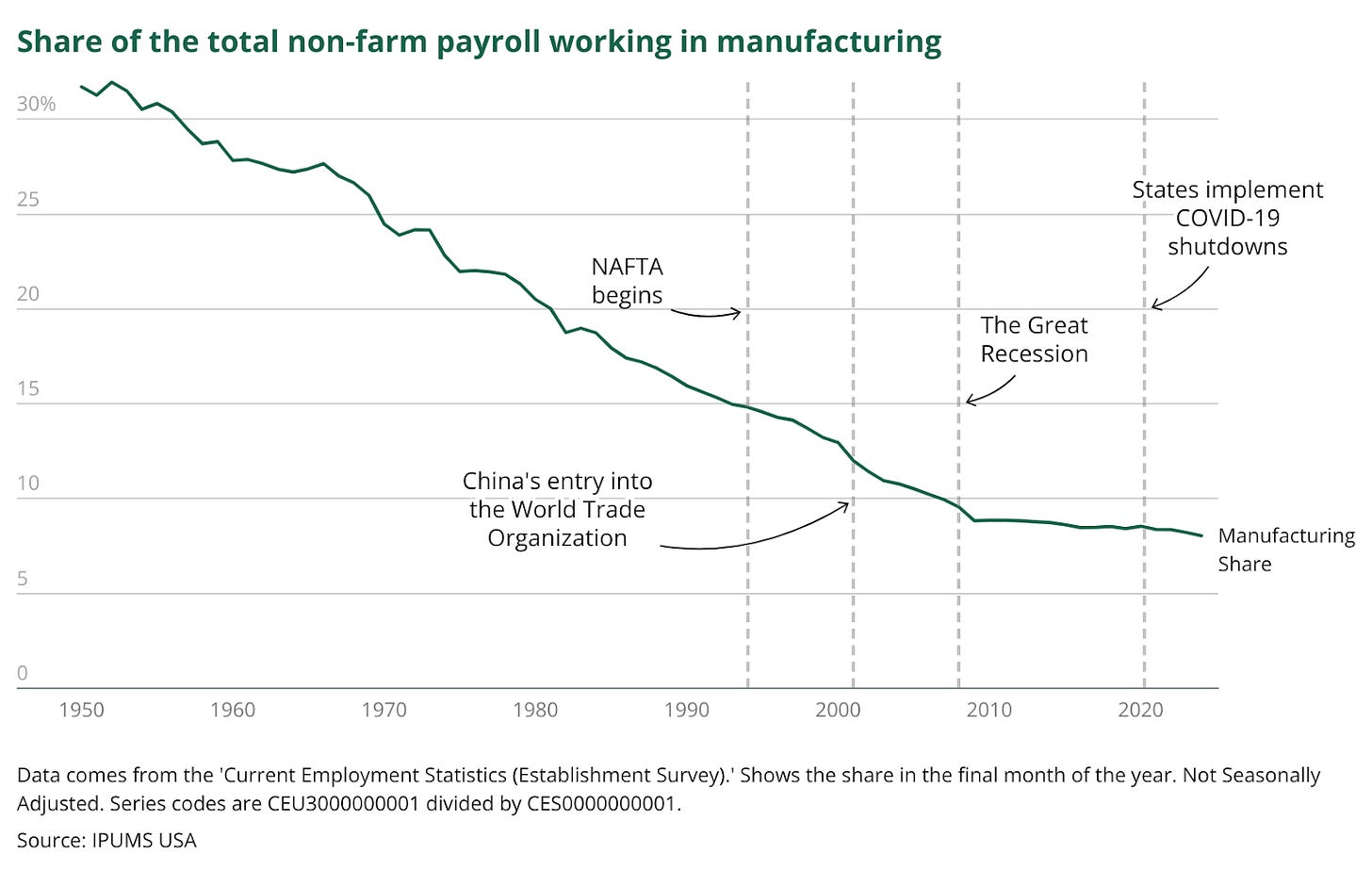

In 1950, roughly 32 percent of (non-farm) employees worked in manufacturing. The share has fallen almost without interruption ever since, and by last year it was just 8 percent.

In other words, the share of workers in factory jobs began declining before the COVID-19 pandemic, before the Great Financial Crisis, before the China Shock, before the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and even before the stagflation of the 1970s.

That’s a familiar story. Less familiar is that the nature of manufacturing jobs has also undergone a significant long-term evolution.

Recent evidence suggests that the quality of surviving manufacturing jobs has held up well for those who remain employed in the sector. Here is what else we know about them:

Modern factories are highly automated. Even traditionally labor-intensive industries have adopted automation to remain cost-competitive. Given prevailing wages, labor regulations, and the significant rise in pay among low-wage workers over the past five years, any new American facility would likely rely heavily on robotics and other technologies designed to minimize labor costs.

Skill requirements have also climbed. Today’s production roles often require technical proficiency — such as programming, equipment calibration, and quality-control analytics — rather than traditional assembly-line work.

These higher-skill and more capital-intensive jobs are also more likely to require advanced education than the factory jobs of the past.

So not only are fewer people working in manufacturing relative to the total labor force, but those who do are increasingly less likely to be workers without a college degree. (We are using non-college workers as a proxy for blue collar workers.)

And when we look at the employment options of non-college workers, the case for manufacturing jobs is not even as clear as one might like. Non-college manufacturing workers had a median wage of $22 per hour in 2024, two dollars less than non-college construction workers, for instance.3

If the jobs that return resemble modern manufacturing jobs, then mass hiring of blue collar workers is less likely than it would have been if the jobs had been created three or four decades ago. And for those blue collar workers who do get hired, their wages may well lag behind other sectors that also employ a big share of blue collar workers.

Of course, one of the reasons that modern manufacturing jobs have qualitatively changed is precisely because the jobs that remain are the ones that have endured global competition and automation — and survived. It’s reasonable to wonder if the jobs that return will be less likely to require higher education than the jobs that currently exist.

To which I would respond that manufacturing jobs all over the world — including China — have also increasingly been automated. So even if reshored jobs demand less schooling than today’s jobs, they will probably still require more than they did in the heyday of 20th-century manufacturing.

————————————————————————————

The president and his top officials have promised not only that tariffs will bring jobs back to the country, but that they will bring back specific kinds of jobs for specific kinds of workers in specific kinds of places. They will find that promise hard to fulfill.

Ben Glasner is an economist at the Economic Innovation Group.

See our new Trade Policy Dashboard if you want to monitor the economy for evidence of the strategy’s success or failure.

Hanson and Moretti (2025) define a “good job” as “those in industries in which full-time, full-year workers attain high earnings, conditional on their education, labor-market experience, and demographic characteristics.” They do this using a Mincer wage regression. Good jobs are those that exist in industries in the top third of industry fixed effects.

College-educated manufacturing workers had a median wage of $35, four dollars more than their construction counterparts. These values were calculated using the reported and imputed wages of workers in the Economic Policy Institute’s Microdata Extracts of the Current Population Survey’s Outgoing Rotational Group.