Here are just a few of the striking facts about U.S. government transfers — money that Americans receive from programs like Social Security, Medicare, SNAP, and so on — that EIG included last year in a detailed report and interactive presentation:

Americans received $3.8 trillion in government transfers in 2022, accounting for 18 percent of all personal income in the United States. That share has more than doubled since 1970, when transfers accounted for 8 percent of personal income. (All figures in this post are adjusted for inflation.)

Over the past half century, per capita transfer income has grown nearly three times faster than income from other sources.

In 1970, fewer than 1 percent of counties across the United States — generally the most distressed areas of the country — derived a quarter or more of total personal incomes from government transfers. In 2000, only about 10 percent of counties did. But by 2022, the most recent data year, 53 percent did.

The aging American population is the biggest contributor to the rising transfer share of income, largely because the two biggest components of transfer spending are the old-age benefits of Social Security and Medicare. Consequently, the federal government spends four times as much on each senior as it does on each child.

A second major cause of the rising transfer share is the lagging growth of other, non-transfer income. One major driver of this trend is the slower earnings growth in certain areas of the country. From 1970-2022, 63 percent of U.S. counties have had lower income growth than the country at large.

The third cause of the growth in the transfer share of income is rising healthcare costs. In 1990, for example, real annual Medicare spending per senior was $7,000. By 2022, it had more than doubled to $16,000. Medical costs have risen nearly twice as quickly as overall inflation over the past several decades.

A perhaps surprising non-cause of the rising transfer share: poverty alleviation and income maintenance programs, including the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The share of government transfer income that these programs account for has fallen from 14.1 percent in 1970 to 11.7 percent in 2022.

Having such granular knowledge about the causes of the rising transfer share of income and, in particular, its geographic distribution throughout the country seems especially useful at a time when so much attention is focused on the national debt and the trajectory of future deficits.

When we first released our findings, they were featured in the Wall Street Journal (which published its own story and interactive based on our work) in addition to The Washington Post, Axios, Business Insider, USA Today, and many other media outlets.

We also briefed numerous policymakers and staffers in Congress about our analysis. Our interactive made it possible to view the transfer share and its historical trends at the level of individual counties, and we fielded inquiries to produce even more detailed analysis about specific cities and towns. People obviously care about the topic of transfers. They care about the effects of transfers on their own communities.

Which leads us to a problem: We may never again be able to update the public about these trends.

Our analysis was built on data collected by the government and published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Specifically, we used the data table labeled CAINC35 — and the BEA informed us last October that it would no longer publish CAINC35 because of budgetary constraints.

The discontinuation of this table means that we will no longer be able to estimate how fast government transfer reliance is growing across different regions of the country. We will no longer be able to identify, for example, the extent to which transfer reliance in different counties is being driven by Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, or Income Maintenance programs. Beyond 2022, the money from each of these transfers can no longer be separated out.

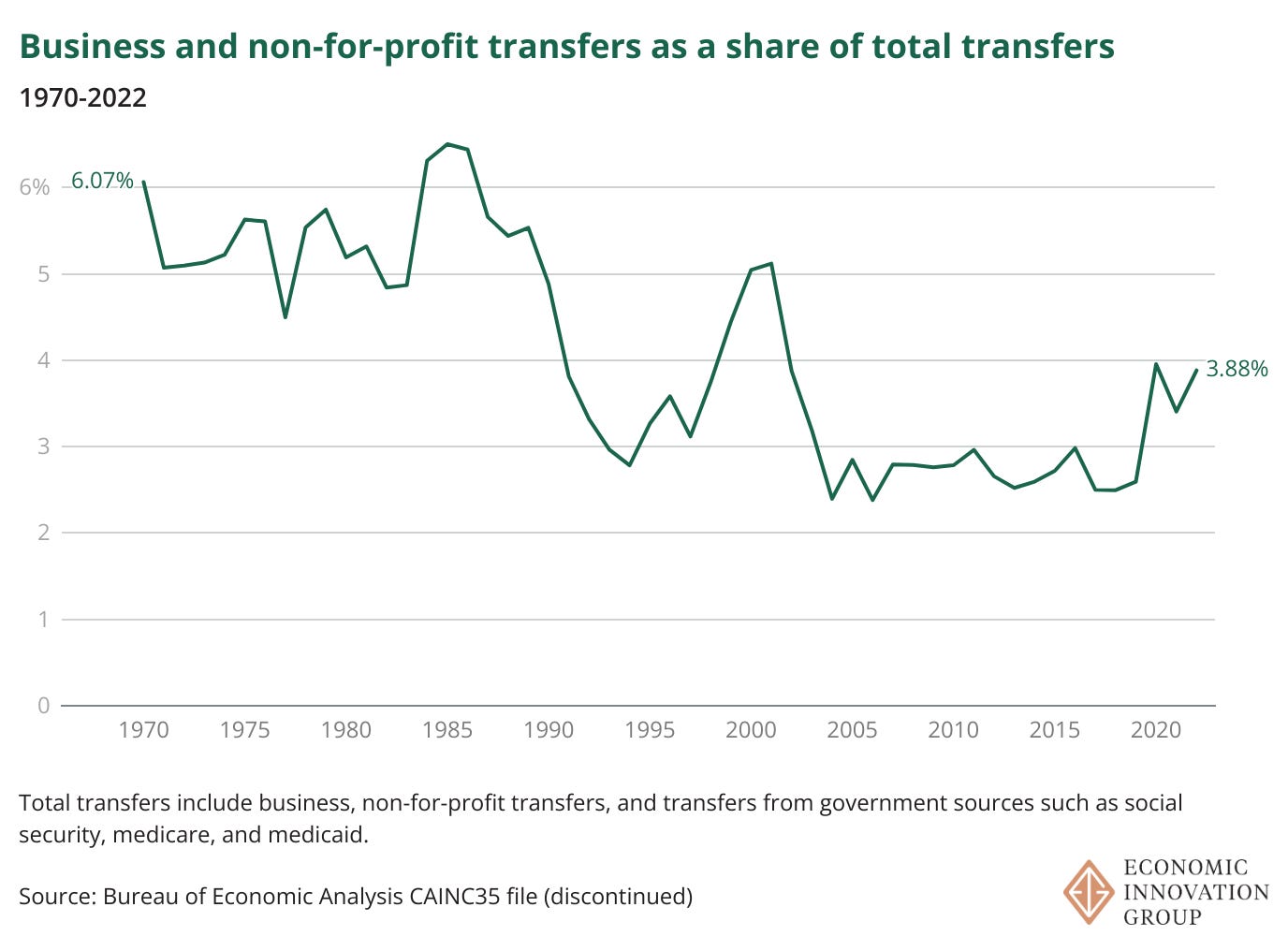

The only transfer data that will now be available at regional levels — for metro areas, counties, states, and so on — is an aggregate total that combines all transfer payments, lumping together not just all the distinct government transfers but also transfers from private businesses and nonprofits.1 Given that private transfers are volatile, fluctuating from year to year, it thus becomes impossible to estimate how much a given state, county, or metro area has received in government transfers over time.2 The significance or insignificance of particular government transfers to a given place’s economy will be unknown.

Finally, without data for individual counties and other regional geographies, it becomes much harder to analyze the interplay between accelerating demographic aging and local economic stagnation — or consequently how this interplay will affect the composition of future incomes for these areas. Nor can we quantify the implications of ongoing rural population loss on transfer reliance, or the extent to which income growth in urban areas is staying ahead of the demographic headwinds. More broadly, understanding these localized economic relationships can inform the public’s understanding of the role of transfers, government outlays, debt, and deficits for the country as a whole.

The economic consequences of flying blind

The BEA’s overall budget, as you can see in this graph, has actually climbed in recent years, but it is possible that the budget constraints cited by the agency have been applied specifically to the part of the BEA that publishes this table.

We contacted the BEA to request more details about the budget constraints and the reasons behind their decision to discontinue CAINC35, but we have yet to hear back. We will update this post with more information if we do. Whatever the explanation, we hope it isn’t too late for the government to reverse course.

The discontinuation of CAINC35 happened last year, when other BEA data tables were also discontinued. But we are writing this post in the immediate aftermath of the removals (some temporary) by the U.S. statistical agencies of other sources of data and documentation that had previously been available to the public. These removals included thousands of pages from the Census Bureau’s web site and were in response to orders from the White House.3

Some of the data has been made available again. But we noticed, for example, that several important files of the Business Dynamic Statistics — which is published by the Census Bureau and provides information about job creation, job destruction, firm startups and closures, and other indicators of economic dynamism — were taken down and remain down.4

And all this activity comes after other worries about the stability of government data had already been accumulating for months and even years. A recent article from NPR’s Hansi Lo Wang titled “Experts warn about the 'crumbling infrastructure' of federal government data” summarizes these concerns:

In recent months, budget shortfalls and the restrictions of short-term funding have led to the end of some datasets by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, known for its tracking of the gross domestic product, and to proposals by the Bureau of Labor Statistics to reduce the number of participants surveyed to produce the monthly jobs report. A "lack of multiyear funding" has also hurt efforts to modernize the software and other technology the BLS needs to put out its data properly, concluded a report by an expert panel tasked with examining multiple botched data releases last year.

Long-term funding questions are also dogging the Census Bureau, which carries out many of the federal government's surveys and is preparing for the 2030 head count that's set to be used to redistribute political representation and trillions in public funding across the country. Some census watchers are concerned budget issues may force the bureau to cancel some of its field tests for the upcoming tally, as it did with 2020 census tests for improving the counts in Spanish-speaking communities, rural areas and on Indigenous reservations.

The statistical agencies of the United States provide some of the most reliable and comprehensive economic indicators of any country in the world. Critical research about the American economy, including our Transfers report, hinges on their ongoing publication.

Any erosion in the country’s ability to offer a clear and timely look at the economy would reduce confidence in the economy itself. Businesses and investors and entrepreneurs would lack the information they need to make good decisions and take the kinds of risks that generate innovation and dynamism. The public would find it more difficult to hold politicians accountable. And policymakers would struggle to respond appropriately to emerging developments in an economy that only becomes more and more complex through the years.

It’s hard to fix a problem if we can’t identify it in the first place.

Private transfers include Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans; Pell grants; other education and training programs administered by nonprofits; receipts from insurance companies (commercial, automobile liability, medical malpractice, and net insurance settlements); corporate cash prizes; business losses due to fraud and unrecovered thefts; receipts from personal injury trust funds; and more. See page 71 at this link for more information.

The high variability of private transfers is evident in this chart, which clearly shows that the private transfer share of overall transfers can change sharply through the years, making it unhelpful to simply lump together government transfers and private transfers.

According to the most recent data release for 2023, total transfers — including transfers from nonprofits and businesses — stood at $4.11 trillion in 2022 dollars. This total is slightly down from $4.14 trillion in 2022. Transfers per capita also fell, just slightly, from $12,420 to $12,280, and transfers as a share of personal income declined from 18.7% to 18.3%.

These results are unsurprising given the ending of pandemic related transfer programs and the continued economic recovery. Unfortunately, without further information on the breakdown by transfer program types, we cannot know how these post-pandemic dynamics are playing out across sources of transfer income, and how those sources vary across the country.

The removals of datasets and web sites from across the government’s statistical agencies have been widely reported. For further reading, try the articles in The New York Times, The Associated Press, The Boston Globe, Slate, USA Today, and Time.

Some of the specific files taken down include state by firm size, state by metro/non-metro, and metro/non-metro by NAICS sector. We relied on these and other files when constructing our recent year-end analysis of U.S. economic dynamism for 2024.